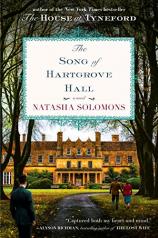

Natasha Solomons is a screenwriter and the author of the New York Times bestseller THE HOUSE AT TYNEFORD. Her upcoming book, THE SONG OF HARTGROVE HALL (which releases on December 29th), is a breathtaking tale of love and treachery, joy after grief, and the never-ending search for redemption --- all set against the backdrop of an English country estate. Natasha’s interest in historical old things extends beyond her fiction and into her real life. Here, she tells the story of an old book of poems, an even older house, and the first Christmas in a home all her own.

Natasha Solomons is a screenwriter and the author of the New York Times bestseller THE HOUSE AT TYNEFORD. Her upcoming book, THE SONG OF HARTGROVE HALL (which releases on December 29th), is a breathtaking tale of love and treachery, joy after grief, and the never-ending search for redemption --- all set against the backdrop of an English country estate. Natasha’s interest in historical old things extends beyond her fiction and into her real life. Here, she tells the story of an old book of poems, an even older house, and the first Christmas in a home all her own.

Old houses, like old books, have a distinctive smell. The book with the richest scent was given to me on Christmas Day, 2005. I was 25 and had just bought my first-ever house with my soon-to-be-husband. It was a tiny stone cottage in Thomas Hardy’s village of “Marlott.” If we stooped to peer out of the low bedroom window, we could spy Tess of the D’Urbervilles’ cottage across the field and beyond the green mantle of the Blackmore Vale. Our little house was ancient, with lime-washed walls and a deeply grooved flagstone floor that was always cold. The only bathroom and loo was downstairs, through the sitting-room, dining room and kitchen. In the night, I’d scurry down and traipse across the flags in my bare feet thinking of Hardy’s lines: “Here is the ancient floor,/ Footworn and hollow and thin/ Here is the ancient door/ Where the dead feet walked in.”

There was no central heating, only decrepit storage heaters that took two days to warm up and a cantankerous wood-burning stove that guzzled fuel and begrudgingly spewed out a dribble of warmth in return. No one had lived there for several years, and when we’d collected the keys from the estate agent a few days earlier and ventured inside, we both had a shiver of doubt. It was so dark and cold and old. The dark beams and low ceilings that had seemed evocative a few weeks ago now oppressed us. The scent of earth and damp rose up through the gaps in the flags, and the walls were cool and wet. My fiancé grumbled about “horrible mistakes.” I cried. We turned on the storage heaters, waited for them to warm the walls and moved back in with my parents.

There was no central heating, only decrepit storage heaters that took two days to warm up and a cantankerous wood-burning stove that guzzled fuel and begrudgingly spewed out a dribble of warmth in return. No one had lived there for several years, and when we’d collected the keys from the estate agent a few days earlier and ventured inside, we both had a shiver of doubt. It was so dark and cold and old. The dark beams and low ceilings that had seemed evocative a few weeks ago now oppressed us. The scent of earth and damp rose up through the gaps in the flags, and the walls were cool and wet. My fiancé grumbled about “horrible mistakes.” I cried. We turned on the storage heaters, waited for them to warm the walls and moved back in with my parents.

On Christmas Eve, I was determined: We were going to move into our house. We cleaned, evicted the earthworms that had squeezed through the gaps in the flags, and lit a fire in the wood burner. We drank gin and warmed inside and out, pondered aloud whether it was going to snow for our wedding in a few days time. In the candlelight, we noticed notches like runes in the vast beam above the inglenook. For the first time in my life, I went to bed in my very own house.

We woke up on Christmas morning with an absolute thrill. While David and I are both Jewish, we adore Christmas, and Dorset is the place for it. We lit another fire and drank coffee in mismatching cups, still in our pyjamas, and David handed me a present. A Christmas present and a wedding present, he explained.

David and I had met in Glasgow while I was studying for a PhD in 18th-century poetry. My passion was a poet named Anna Laetitia Barbauld --- one of the most remarkable and overlooked writers of the time. She was famed for a collection of poems published in 1773 when she was a young woman.

I put down my coffee and unwrapped my present: a first edition of Anna Laetitia Barbauld’s POEMS (London: Printed for Joseph Johnson, in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, 1773). I cried for the second time in as many days, but this time with happiness. When a house is as old as ours was --- it was built sometime in the late 1600s --- it takes time to reconcile oneself with its former inhabitants. In my mind, I could hear the ghosts of ancient feet and the murmurs of hundreds of years of memories accumulated in the walls. Yet, with the gift of Barbauld’s POEMS, we had our first memory, and the cottage started to feel like our home. I sniffed the book, and it smelt gloriously of dust and smoke. I placed it on a makeshift shelf. 1773. The poetry book still wasn’t as old as the cottage.