Milch Cow

Review

Milch Cow

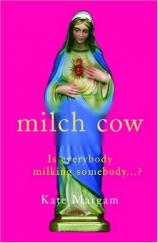

It is with profound shamefacedness that I admit to picking up Kate Margam's MILCH COW for the most embarrassingly superficial of reasons. (1) It was short. (2) Margam is British and I, in true lemming-like fashion, suffer from that ubiquitous malady, Anglophilia. (3) The front cover featured a statue of the Virgin Mary holding her left breast against a hot pink background while the back cover blurb read as such: A night in the '80s. A young city dealer, intoxicated by money and cocaine, leaves a nightclub… Actually, the blurb was comprised of at least five or six additional sentences but I never got past this first one because, between those few words and the cover, I was already wooed by the retro and ironic possibilities.

So there it is. Charlatan that I am, I entered into this book hoping for some tongue-in-cheeky romp through the London's sinfully excessive "Me Generation." Well, you can only mockingly laugh at my surprise when, upon turning to page one, I was hit with the realization that I was not about to be treated to Britain's answer to Bret Easton Ellis. MILCH COW was rife with commentary; Margam had an agenda.

Initially set against the backdrop of Britain's tumultuous mining strike in the mid-'80s, MILCH COW chronicles the 15-year emotional odyssey of a family coming to grips with the devastating loss of a loved one while quagmired in "detached, four-bedroom complacency." Once beautiful (now old and saggy), Sylvia is the picture of suburban ennui --- from the pride/jealousy admixture she feels toward her free-spirited, passionate, artistic daughter Samantha right down to her sexless marriage to the boringly respectable, intimacy-challenged Alun. The only thing Sylvia has that is truly "hers" is the lump she finds in her left breast. She clings to the lump like a child, cradling it in her right hand, coaxing it back to the surface when it recedes.

The discovery of the lump starts Sylvia down the path of self reevaluation, but it's not until the sudden death of her son, Marcus, that she --- indeed the whole family --- is thrust from her complacency. Over the course of the next 15 years, as the miners' strike gives way to the equally charged political climate of the Labour Party's rise to power in the late '90s, the characters inexorably change. Sylvia undergoes some sort of spiritual epiphany, evidenced not so much by her saying anything as tangible as "I have undergone some sort of spiritual epiphany," but by her twice saying the rosary and thrice experiencing visitations from The Virgin. She also becomes involved in a torrid affair with Jeremy, her next-door neighbor and longtime family friend. Jeremy, a generally deficient human being more concerned with looking like an upstanding citizen than actually being one, eventually comes to fall in love with Sylvia and, on his death bed (he unexpectedly dies of a heart attack, an event that precipitates yet another reevaluation for Sylvia and paves the way for her return to the patiently waiting Alun) finally comes to recognize and regret his generally deficient humanity.

Midway through this 15 year grieving process, Sylvia and Alun learn that Marcus, the child with whom Sylvia felt a special connection (Samantha always kept herself at arm's length), was not the quiet, conservative stockbroker they thought he was, but rather an openly gay, socialist, drug-addicted stockbroker likely suffering from AIDS. Shocked for but a moment, Sylvia --- without much explanation beyond "she heard the stories and the venomous things some people said about AIDS. Some of them Christians too. It made her angry. It made her want to fight them. She wanted to shout 'My son was gay and I would challenge anyone not to have loved him.' She became a tireless and deeply committed campaigner." --- fervently takes up the causes of gay rights and AIDS awareness. Alun, playing the stereotypical, impervious male role, retreats even further into himself.

The news of Marcus's purported sickness reaches Samantha (she was already privy to his homosexuality) on October 16, 1992 --- the day the British stock market crashes. Ironically, Samantha makes a small fortune off the money Marcus left her due to some smart buying and selling. Although deeply hurt that her brother, the one person who really "understood" her, would keep such a secret, Samantha decides that what really matters is that he loved her. She further decides she wants nothing to do with the money and gives it all away to her father to start up a new business after losing his in the market crash. Further still, she decides to become a militant Greeenpeacer and "go underground" because "she had felt sure that if Marcus were alive, environmental issues would be the most important thing to him."

For such a slender offering, there is an awful lot going on in MILCH COW (see the previous four paragraphs). Perhaps a little too much. There is so much potential significance attached to Margam's central plotline --- a family torn apart by unimaginable tragedy struggling to find a way to reunite --- what with all the added sociopolitical undercurrents streaming throughout the story, you can't help but feel its emotional depth isn't being fully plumbed. When, in the course of her endless, adolescent, anti-establishment soapboxing did Samantha find the time to come to terms with her brother's death and have a meaningful, recognizable self-actualization? And while we learn that Alun's loyalties are torn between the Tories and the Labourers, we are offered only a perfunctory peek into his feelings about Sylvia's brazen new lifestyle and almost nothing on Marcus's death and posthumous coming out of the closet.

If she were one of Margam's children, it would be readily apparent that Sylvia was the favorite, as the process through which she works through her grief is infinitely more compelling than that of any other character. However, there are certain shortcomings in her story as well --- shortcomings that could have been avoided if Margam weren't trying to render a dramatic storytelling and espouse a variety of political and social "truths," all within 180 pages. Sylvia's spiritual awakening, for instance, isn't treated with as much insight as one would expect from such a momentous event, particularly when juxtaposed with the sexual awakening she was also having. Most people would probably think finding God and becoming an adulterer where inherently incongruous. That Margam suggests otherwise is quite interesting. Unfortunately, she never really delves into the implications of undergoing a spiritual rebirth simultaneous to the shedding of a repressed, 1950s imprinted self. Part of the problem is also that Margam does such an excellent job of capturing the powerful viscerality between Sylvia and Jeremy --- Margam has a definite flair for sex scenes --- that the profundity of Sylvia's religious epiphany is more than a little undercut.

The intent behind MILCH COW --- to interweave a personal story with an overarching social commentary --- reminds me of the "So What?" policy adopted by my English professors in college. For a paper to be truly good, it must not only offer a close reading of the text, it must also make a greater statement about history, society, the human condition, literature, etc. Finding that hook, that "So What?", was not always easy, nor was striking the right balance between penetrating character analysis and broader social context. The question Margam begs, "Is everybody milking somebody…?" is obviously valid, certainly timely and undeniably important. It's a great hook. But while Margam's prose is generally quite deft, MILCH COW's fusion of the personal and the political doesn't quite strike that perfect balance.

Reviewed by Sarah Brennan on May 1, 2001

Milch Cow

- Publication Date: May 1, 2001

- Genres: Fiction

- Paperback: 184 pages

- Publisher: Serpent's Tail

- ISBN-10: 1852426012

- ISBN-13: 9781852426019