Excerpt

Excerpt

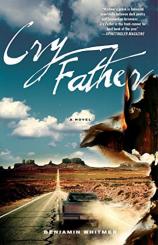

Cry Father

Justin,

I didn’t keep a gun around the house when we had you. They make your mom nervous, for one thing. For another, there didn’t seem a whole lot of need when I was working Questa and Taos. I looked forward to teaching you how to shoot, though. I don’t hunt much, but I like skeet shooting. I figured that sooner or later I’d buy a little .410 single shot for your own. I had it in my mind. Just like teaching you how to throw a baseball. Or fishing. All of those father-and- son moments you see on television. But shooting was one of those many things I didn’t get around to when you were alive. It seems like my memory’s nothing but a series of holes where those moments should be. Moments I spent drinking beer, sitting on the front porch. Moments I spent wondering how the hell I ended up settled down in Questa, New Mexico.

It was only after you died that I started carrying a gun full-time. I was in Louisiana, just after Hurricane Katrina. I’d never carried one up until then, even when I was working with the worst crews. Most of the men I was with aren’t exactly opposed to violence. That comes with the job. Hell, when you’re young, it’s part of the attraction. When you still give a shit about things like whether you can hold your own in a fight, you’re more than happy to work with those kind of men.

It’s a job that attracts that kind, I guess. The kind of men who get shaken out of normal life and collected at the bottom. I ain’t saying everybody, but I doubt there’s any occupation with a greater percentage of convicts, drunks, and addicts. It’s just the way it is. Even so, they never scared me enough I felt like I needed a gun. A good clip knife was fine.

Besides which, almost all the danger we faced came from our work. Especially since the men I worked with didn’t exactly hold safety as their highest priority. I know I didn’t when I was younger. I worked an entire season once dropping LSD every morning, and I don’t know anybody who works strictly sober. Men fall out of trees, men amputate themselves, and when there ain’t easy access to medical help, men bleed out. When that happens, there’s not a whole lot to do but watch them die while the foreman tries to call whoever the hell he’s supposed to. A gun’s not of much use in that situation.

But Louisiana after Katrina, that was different. Where we were camped, you could hear gunfire most hours of the night or day, and we weren’t even close to the worst of it. We just tried to keep our heads down, work on clearing the lines of debris, and let everything else take care of itself. But still, we heard stories about what was going down. People being gunned down by vigilantes and rogue cops. Whole blocks tagged “Dead Body Inside,” nobody even bothering to remove them. Refugees from the city being turned away at gunpoint from higher ground.

We didn’t belong there. Everybody knew we didn’t belong there. And we were working equipment worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, all of which was exactly what every person there needed. Most things lose their value after a hurricane, but bucket trucks and chain saws don’t, not for anybody who’s got a house buried under rubble. We were targets and there wasn’t one of us who didn’t know it.

And then there were the bigger stories. Blackwater mercenaries cleaning out the most desirable New Orleans real estate. Developers buying up the newly vacated land, planning condos, already rebuilding New Orleans as a cheap theme park of itself. Corporations moving in to take over everything they could get their hands on, right down to the schools and hospitals. And the big story, the one everybody believed. That the Lower Ninth Ward levees had been deliberately breached, smashed by a barge in order to save the French Quarter. I didn’t meet a single person who lived near the levees who didn’t tell me that story.

It was hearing those stories that made me realize I wanted something besides a pocketknife to protect myself. It was not having any idea what was actually going on. So I bought a 1911 from a street kid I found walking a wheelbarrow of looted goods past our bucket truck in Jefferson Parish. He told me it was junk, that it’d jam up every time after the first round, so I only had to give him a hundred dollars for it.

The thing is, I knew exactly what was wrong with the gun the minute that street kid told me the problem. My father, your grandfather, he carried one of those every day of his life. He was a Vietnam veteran and he didn’t go anywhere without his service issue .45 Colt 1911A1. One of the many gifts given him by the Vietnam War was that he had more conspiracy theories than Brother Joe, and all his theories made him feel a hell of a lot better armed.

So I sat down in the street right there, took the extractor out of the slide, and tensioned it with my thumbs. It’s run like a top ever since, and when I got back to Colorado that summer, I applied for my concealed-carry permit. It’s good in most states, and now I’ve got just one rule. I won’t work anywhere I can’t carry. That’s my only rule.

Cry Father

- Genres: Fiction

- paperback: 320 pages

- Publisher: Gallery Books

- ISBN-10: 1476734364

- ISBN-13: 9781476734361