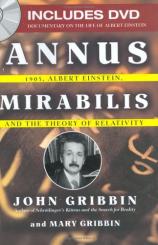

Annus Mirabilis: 1905, Albert Einstein, and the Theory Of Relativity

Review

Annus Mirabilis: 1905, Albert Einstein, and the Theory Of Relativity

Albert Einstein's last words are the only secret he left behind.

After a lifetime of scientific achievement the world had not seen

since Galileo and Newton, the twentieth century's greatest thinker

and theorist offered a few words in German and died on April 18,

1955. The nurse at his hospital bedside did not speak the

language.

This little irony followed a career that altered the way we think

about the universe and our place in it. Yet, as John and Mary

Gribbin reveal, what is most breathtaking about Einstein's life is

that his greatest theories were written in four scholarly papers in

just one "miraculous year," 1905. "What made Einstein so special,"

the authors write, "and the annus mirabilis so miraculous, was that

all four pieces of work were produced by the same young man,

working outside the mainstream of scientific life, in his spare

time, while holding down a demanding job…"

Through his youthful conceit and cockiness, Einstein placed himself

outside academia and in a patent office, the last place anyone

would expect a man who would achieve such greatness to work. Born

in Ulm, Germany in 1879 to Jewish parents, young Albert was slow to

learn to speak and was "prone to outbursts of temper," including

one incident when he threw a chair at his violin teacher and chased

her out of the house. He was bored by school but dove into the

Jewish religion with a fervor that burned itself out by the time he

was twelve. He discovered the wonder of science from a friend named

Max Talmey who gave him a geometry book.

Einstein quit high school by being "a know-it-all troublemaker" and

wound up at the Swiss Federal Polytechnic in Zurich. As Einstein

himself often expected, he was recognized for his brilliance and

talent. He became interested in the behavior of light, energy,

matter and the forces that play upon them. Love interests bloomed

for the young scientist, but none so important --- or as the

Gribbins assert, "disruptive" or "problematic" --- as that of

Mileva Maric. While she enthusiastically shared Einstein's

scientific interests, the authors clearly have no respect for

Mileva, who eventually married Einstein in 1903 and gave birth to

his two boys. Albert and Mileva's love was not without scandal ---

their first child, a girl, was delivered prior to their marriage

but was adopted and never heard from again.

Failing to forge a proper reputation to be accepted as a university

professor, Einstein took a job in a patent office and tutored to

support his family. He was a loving father, but not a doting one.

The Gribbins write, "…when he was supposed to be looking

after the baby he might be found with a pipe in his mouth, rocking

the cradle with one hand while writing out calculations on his

ubiquitous notepad with the other."

He was twenty-six when the four famous scientific papers were

written. The first, establishing the reality of light quanta,

earned the Nobel Prize sixteen years later. The second paper was a

doctoral thesis that became his most quoted work. The third proved

the reality of atoms, while the fourth, which was later revised,

offered the theory of relativity: "a complete description of the

relationship between space, time, and matter on a large

scale…" Once published, these essays drew gradual

attention.

The respect of fellow scientists built for Einstein the reputation

he deserved. The attention and attractive offers from universities

around the world finally lured Einstein from his wife and children.

After a breakdown in 1917, he was nursed back to health by his

cousin Elsa with whom he fell in love. She mothered him in a way

that Mileva could not and was his constant companion. Once healthy,

he toured and was treated like a "modern pop star" when he visited

the United States in 1921.

Though the Gribbins' biography of Einstein has its scholarly

moments and is based largely on other biographies and previously

published letters, ANNUS MIRABILIS is a worthy, accessible and, at

times, gripping read. A supplemental, and similar, work not

utilized by the authors but also valuable is EINSTEIN AND OUR WORLD

by David Cassidy. The Gribbins carefully point out that physicist

Einstein did not experiment. He based the foundations of his

theories on the experiments of other scientists.

What made Einstein great? His creativity and his clear status as a

visionary, boldly setting forth theories that would take other

scientists years to prove true. As an iconic "cross between God and

Harpo Marx," Einstein solved the secret of the universe with his

famous equation. And as Einstein himself foretold just five years

before his death, that secret, in the hands of lesser men, could

destroy the world.

Reviewed by Brandon M. Stickney on December 22, 2010

Annus Mirabilis: 1905, Albert Einstein, and the Theory Of Relativity

- Publication Date: March 29, 2005

- Genres: Biography, Nonfiction

- Hardcover: 320 pages

- Publisher: Chamberlain Bros.

- ISBN-10: 1596091444

- ISBN-13: 9781596091443