Excerpt

Excerpt

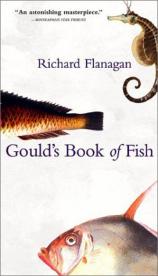

Gould's Book of Fish: A Novel in Twelve Fish

The Pot-Bellied Seahorse

Discovery of the Book of Fish—Fake furniture and faith healing—The Conga—Mr Hung and Moby Dick—Victor Hugo and God—A snowstorm—On why history and stories have nothing in common—The book disappears—Death of Great Aunt Maisie—My seduction—A male seahorse gives birth—The fall.

I

My wonder upon discovering the Book of Fish remains with me yet, luminous as the phosphorescent marbling that seized my eyes that strange morning; glittering as those eerie swirls that coloured my mind and enchanted my soul—which there and then began the process of unravelling my heart and, worse still, my life into the poor, scraggy skein that is this story you are about to read.

What was it about that gentle radiance that would come to make me think I had lived the same life over and over, like some Hindu mystic forever trapped in the Great Wheel? that was to become my fate? that stole my character? that rendered my past and my future one and indivisible?

Was it that mesmeric shimmer spiralling from the unruly manuscript out of which seahorses and seadragons and stargazers were already swimming, bringing dazzling light to a dreary day not long born? Was it that sorry vanity of thought which made me think contained within me was all men and all fish and all things? Or was it something more prosaic—bad company and worse drink—which has led to the monstrous pass in which I now find myself?

Character and fate, two words, writes William Buelow Gould, for the same thing—one more matter about which he was, as ever, incisively wrong.

Dear, sweet, silly Billy Gould and his foolish tales of love, so much love that it is not possible now, and was not possible then, for him to continue. But I fear I am already digressing.

We—our histories, our souls—are, I have since come to believe in consequence of his stinking fish, in a process of constant decomposition and reinvention, and this book, I was to discover, was the story of my compost heap of a heart.

Even my feverish pen cannot approach my rapture, an amazement so intense that it was as if the moment I opened the Book of Fish the rest of my world—the world!—had been cast into darkness and the only light that existed in the entire universe was that which shone out of those aged pages up into my astonished eyes.

I was without work, there being little enough of it in Tasmania then and even less now. Perhaps my mind was more susceptible to miracles than it might otherwise have been. Perhaps as a poor Portuguese peasant girl sees the Madonna because she doesn’t wish to see anything else, I too longed to be blind to my own world. Perhaps if Tasmania had been a normal place where you had a proper job, spent hours in traffic in order to spend more hours in a normal crush of anxieties waiting to return to a normal confinement, and where no-one ever dreamt what it was like to be a seahorse, abnormal things like becoming a fish wouldn’t happen to you.

I say perhaps, but frankly I am not sure.

Maybe this sort of thing goes on all the time in Berlin and Buenos Aires, and people are just too embarrassed to own up to it. Maybe the Madonna comes all the time to the New York projects and the high-rise horrors of Berlin and the western suburbs of Sydney, and everybody pretends she’s not there and hopes she’ll just go away soon and not embarrass them any further. Maybe the new Fatima is somewhere in the vast wastelands of the Revesby Workers’ Club, a halo over the pokie screen that blinks ‘BLACKJACK FEVER’.

Could it be that when all backs are turned, when all faces are focused on the pokie monitors, there is no-one left to witness the moment an old woman levitates as she fills in her Keno form? Maybe we have lost the ability, that sixth sense that allows us to see miracles and have visions and understand that we are something other, larger than what we have been told. Maybe evolution has been going on in reverse longer than I suspect, and we are already sad, dumb fish. Like I say, I am not sure, and the only people I trust, such as Mr Hung and the Conga, aren’t sure either.

To be honest, I have come to the conclusion that there is not much in this life that one can be sure about. Despite what may come to seem to you as mounting evidence to the contrary, I value truth, but as William Buelow Gould continued to ask of his fish long after they were dead from his endless futile queries, where is truth to be found?

As for me, they have taken the book and everything away now, and what are books anyway but unreliable fairy tales?

Once upon a time there was a man called Sid Hammet and he discovered he was not who he thought he was.

Once upon a time there were miracles, and the aforementioned Hammet believed he had been swept up in one. Until that day he had lived by his wits, which is another, kinder way of saying that his life was an ongoing act of disillusionment. After that day he was to suffer the cruel malaise of belief.

Once upon a time there was a man called Sid Hammet who saw reflected in the glow of a strange Book of Fish his story, which began as a fairy tale and ended as a nursery rhyme, riding a cock-horse to Banbury Cross.

Once upon a time terrible things happened, but it was long ago in a far-off place that everyone knows is not here or now or us.

II

Until that time I had devoted myself to buying old pieces of rotting furniture which I further distressed with every insult conceivable. While I belted the sorry cupboards with hammers to enhance the pathetic patina, as I relieved myself on the old metalwork to promote the putrid verdigris, yelling all manner of vile curses to make myself feel better, I would imagine that such pieces of furniture were the tourists who were their inevitable purchasers, buying what they mistakenly thought to be flotsam of the romantic past, rather than what they were, evidence of a rotten present.

My Great Aunt Maisie said it was a miracle that I had found any work, and I felt she would know, for had she not taken me at the age of seven to the North Hobart oval in the beautiful ruby light of late winter to miraculously assist North Hobart win the football semi-final? She sprinkled Lourdes holy water from a tiny bottle on the muddy sods of the ground. The Great John Devereaux was captain coach and I was wrapped in the Demons’ red and blue scarf, like an Egyptian’s mummified cat, with only big curious eyes visible. I ran out at three-quarter time to peek through a mighty forest of the players’ Deepheat-aromaed thighs and hear the Great John Devereaux deliver a rousing speech.

North Hobart were down a dozen goals and I knew he would say something remarkable to his players, and the Great John Devereaux was not a man to disappoint his followers. ‘Get your minds off the fucking sheilas,’ he said. ‘You, Ronnie, forget that Jody. As for you, Nobby, the sooner you get that Mary out of your mind, the better.’ And so on. It was marvellous to hear all those girls’ names and know they meant so much to such giants at three-quarter time. When they then won, kicking into the wind, I knew that love and water was a truly unbeatable combination.

But to return to my work with furniture, it was, as Rennie Conga (this, I hasten to say, lest some of her family read this and take umbrage, was not exactly her name, but no-one could ever remember her full Italian surname and it somehow seemed to fit her sinuous body and the close, dark clothes with which she chose to clad that serpentine form), my then probation officer, put it, a post with prospects, particularly when the cruise ships full of fat old Americans came by. With their protruding bellies, shorts, odd thin legs and odder big white shoes dotting the end of those oversize bodies, the Americans were endearing question marks of human beings.

I say endearing, but what I really mean to say is that they had money.

They also had their tastes, which were peculiar, but where commerce was concerned I was fond enough of them—and they of me. And for a time the Conga and I did a good line in old chairs which she had bought at an auction when yet one more Tasmanian headquarters of a government department had closed down. These I painted in several bright enamel paints, sanded back, lightly shredded with a vegetable grater, pissed on and passed off as Shaker furniture that had come out with whalers from Nantucket last century in, as we would say in answer to the question marks, their ceaseless search of the southern oceans for the great leviathans.

It was the story, really, that the tourists were buying, of the only type that they would ever buy—an American story, a happy, stirring tale of Us Finding Them Alive and Bringing Them Back Home—and for a time it was a good story. So much so that we ran out of stock and the Conga was forced to set up a production side to our venture, securing a deal with a newly arrived Vietnamese family, while I had the story neatly typed up along with some genuine authentication labels by a bogus organisation we called the Van Diemonian Antiquarian Association.

The Vietnamese’s story (his name was Lai Phu Hung but the Conga, who believed in respect, always insisted on us calling him Mr Hung) was as interesting as any old whaling tale, his family’s flight from Vietnam more perilous, their voyage in an overcrowded and derelict fishing junk to Australia more desperate, and they were better at scrimshaw to boot—a sideline, I should add, in which we also did a respectable trade. As the templates for his bone carving, Mr Hung used the woodcut illustrations out of an old Modern Library edition of Moby Dick.

But he and his family had no Melville, no Ishmael or Queequeg or Ahab on the quarterdeck, no romantic past, only their troubles and dreams like the rest of us, and it was all too dirtily, irredeemably human to be worth anything to the voracious question marks. To be fair to them, they were only after something that walled them off from the past and from people in general, not something that offered any connection that might prove painful or human.

They wanted stories, I came to realise, in which they were already imprisoned, not stories in which they appeared along with the storyteller, accomplices in escaping. They wanted you to say, ‘Whalers’, so they might reply, ‘Moby Dick’, and summon images from the mini-series of the same name; so you might then say, ‘Antique’, so they might reply, ‘How much?’

Those sort of stories.

The type that pay.

Not like Mr Hung’s tales, which no question marks ever wanted to hear, something of which Mr Hung seemed extraordinarily accepting, in part because his true ambition was not to be a steam-crane driver as he had been in Hai-Phong City, but a poet, a dream that allowed him to affect a Romantic resignation to the indifference of a callous world.

For Mr Hung’s religion was literature, literally. He belonged to the Cao Dai, a Buddhist sect that regarded Victor Hugo as a god. In addition to worshipping the deity’s novels, Mr Hung seemed knowledgeable about (and intimated a certain spiritual communion with) several other greats of nineteenth-century French writing of whom, beyond their names—and sometimes not even that—I knew nothing.

Being in Hobart and not Hai-Phong City, the tourists cared not a jot for the likes of Mr Hung, and they certainly weren’t going to give us any money for his tales about steam cranes, or his father’s cranes that fished, or his poetry, or, for that matter, his thoughts on the connections between God and Gallic literature. And so instead Mr Hung dug out a small workshop beneath his old Zinc Company house in Lutana and set to work building fake antique chairs and carving ersatz whalebone to complement our more sordid fictions.

And why should Mr Hung or his family or the Conga or I have cared anyway?

The tourists had money and we needed it; they only asked in return to be lied to and deceived and told that single most important thing, that they were safe, that their sense of security—national, individual, spiritual—wasn’t a bad joke being played on them by a bored and capricious destiny. To be told that there was no connection between then and now, that they didn’t need to wear a black armband or have a bad conscience about their power and their wealth and everybody else’s lack of it; to feel rotten that no-one could or would explain why the wealth of a few seemed so curiously dependent on the misery of the many. We kindly pretended that it was about buying and selling chairs, about them asking questions about price and heritage, and us replying in like manner.

But it wasn’t about price and heritage, it wasn’t about that at all.

The tourists had insistent, unspoken questions and we just had to answer as best we could, with forged furniture. They were really asking, ‘Are we safe?’ and we were really replying, ‘No, but a barricade of useless goods may help block the view.’ And because hubris is not just an ancient Greek word but a human sense so deep-seated we might better regard it as an unerring instinct, they were also wanting to know, ‘If it is our fault, then will we suffer?’ and we were really replying, ‘Yes, and slowly, but a fake chair may make us both feel better about it.’ I mean it was a living, and if it wasn’t that good, nor was it all that bad, and while I would carry as many chairs as we could sell, I wasn’t about to carry the weight of the world.

You might think such a venture would have met with the greatest approval, that inevitably it would have progressed, diversified, grown into a redemptive undertaking of global proportions and national merit. It may even have won export awards. Certainly in any city worth its sly salt—Sydney, say—such dreaming fraudulence would have been handsomely rewarded. But this, after all, was Hobart, where dreams remained a strictly private matter.

Following the receipt of several lawyers’ letters from local antique dealers and the attendant threat of legal proceedings, the arse fell out of our noble enterprise of offering solace to a decrepit empire’s retired tribunes. The Conga felt compelled to go into eco-tourism consultancy with the Vietnamese furniture faker, and I went looking for some new lines.

III

So it came to be on that winter’s morning that was to prove fateful but at the time merely seemed freezing, I found myself in the wharf-side area of Salamanca. In an old sandstone warehouse I came upon what was still a junk shop, before that space too was appropriated by tourists and turned into yet another delicately overdone al-fresco restaurant.

Nestled behind some unfashionable 1940s blackwood wardrobes no tourist would ever be interested in receiving as absolution, I chanced to notice an old galvanised-iron meat safe which, with a child’s desire to see into whatever is closed, I opened.

Inside I could only make out a heap of women’s magazines of years gone by, a discovery dusty as it was disappointing. I was already closing the door when, beneath those fading rumours of love and tawdry tales of sad, lost princesses, my eye caught on some brittle cotton threads cheerily jutting out like Great Aunt Maisie’s stubble, without shame and with a certain archaic vigour.

The door scratched a flat note as I pulled it back open and peered more closely inside. I saw that the threads grew out from a somewhat frayed binding, the spine of which had partly fallen away. As carefully as if it were a prize fish hopelessly entangled in my net, I reached in, lifted up the magazines, and from beneath eased out what appeared to be a dilapidated book.

I held it up in front of me.

I put my nose close.

Oddly, it smelt not of the sweet must of old books, but of the briny winds that blow in from the Tasman Sea. I lightly ran an index finger across its cover. Though filthy with a fine black grime, it felt silky to the touch. It was on wiping away that silt of centuries that the first of many remarkable things occurred.

I should have known then that this was no ordinary book, and certainly not one a deadflog like me ought to be getting mixed up with. I know—or at least, I thought I knew—the limits of my criminality, and I believed I had learnt how to say no to any tomfoolery that involved personal risks.

But it was too late. I was—as has been put to me before in the course of legal proceedings—already implicated. For beneath that delicate black powder something highly unusual was happening: the book’s marbled cover was giving off a faint, but increasingly bright purple glow.

IV

Outside it was a melancholic winter’s day.

Snow mantled the mountain above the town. Mist billowed down the broad river, covering like a slow-falling quilt the valley in which lay the quiet, mostly empty streets of Hobart. Through the chill beauty of the morning, a few figures clad in the motley of cold-day clothes scurried, then vanished. The mountain turned from white to grey then disappeared to brood behind black cloud. The town was passing into gentle sleep. Like lost dreams snow began waltzing through its hushed world.

All of which is not totally beside the point, for what I am really trying to say is that it was cold as a tomb and ten times quieter, that there were on such a day no portents, nothing that might have warned me of what was about to happen. And certainly on such a day no-one else bothered to venture into a dark, unheated Salamanca junk shop. Even the owner stayed huddled over a small bar radiator at the far end of his domain, his back turned to me, surreptitiously slipping off that vile anthem of contemporary retailing, Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, and putting on the comforting low rubato of the races, a golden slipper of sound.

No-one else in the world was there to notice, to witness along with me that miracle when the world seemed to contract to a gloomy corner of an old junk shop, and eternity to that moment when I first brushed the silt off the front of that bizarre book.

As with the skin of a bastard trumpeter caught at night, the book’s cover was now a mass of pulsing purple spots. The more I brushed, the more the spots spread, till most of the cover was brightly glowing. As with the night fisherman who handles the bastard trumpeter, the speckled phosphorescence spread from the book onto my hands until they too were covered in purple freckles, twinkling in splendid disarray, like the lights of an exotic, unknown city glimpsed from a plane. As I held my luminous hands up in front of my face and then slowly turned them around in wonder—hands so familiar yet so alien—it was as if I had already begun a disturbing metamorphosis.

I laid the book on a laminex table that sat next to the meat safe, ran my now sparkling thumb up its soft underbelly of unruly, frail pages, and turned the cover. To my wonder the book fell open to a painting of a pot-bellied seahorse. Gathered around the seahorse, like a flotsam of bull-kelp and sea grass, was a rumpled script. Interspersed every so often would be another watercolour painting of a fish.

It was, I must admit, a dreadful hodgepodge, what with some stories in ink layered higgledy-piggledy over others in pencil, and sometimes vice versa. Upon running out of space at the end of the book, the writer seemed to have simply turned it around and, between the existing lines, resumed writing—in the opposite direction and upside down—more of his tales. If this wasn’t confusing enough—and it was—there were numerous addenda and annotations crammed into the margins and sometimes on loose leaves of paper, and once on what looked like dried fish skin. The writer appeared to have press-ganged any material—old sailcloth, edges ripped out of God knows what books, burlap, even hessian—into use as a surface to cover with a colourful, crabbed handwriting that at the best of times was hard to decipher.

The sum of such chaos was that I seemed to be reading a book that never really started and never quite finished. It was like looking into a charming kaleidoscope of changing views: a peculiar, sometimes frustrating, sometimes entrancing affair, but not at all the sort of open-and-shut thing a good book should be.

Yet before I knew it, I was washed far away by the stories that accompanied these fish—if they can even be described as such, the volume being more in the manner of a journal or diary, sometimes of actual events, immersed in the mud of the mundane, at other times of matters so cracked that at first I thought it must be a chronicle of dreams or nightmares.

This weird record seemed to be that of a convict called William Buelow Gould who in the supposed interest of science was, in 1828, ordered by the surgeon of the penal colony of Sarah Island to paint all fish caught there. But while the duty of painting was obligatory, the duty of writing, which the author carried as an additional burden, was not. The keeping of such journals by convicts was forbidden, and therefore dangerous. Each story was written in a different coloured ink which, as their convict scribe describes, had been made by various ingenious expedients from whatever was at hand: the red ink from kangaroo blood, the blue from crushing a stolen precious stone, and so on.

The author wrote in colours; more precisely, I suspect, he felt in colours. I don’t mean he would wax on about wine-dark sunsets or the azure glory of a still sea. I do mean to suggest that his world took on hues that overwhelmed him, as if the universe was a consequence of colour, rather than the inverse. Did the wonder of colour, I pondered, redeem the horror of his world?

This clandestine rainbow of tales, in spite of—and to be truthful, perhaps also because of—its crude style, its many inconsistencies, its difficulty to read, its odd beauty, to say nothing of its more ludicrous and sometimes frankly implausible moments, so captivated me that I must have read at least half before I came to my senses.

I found an old rag on the floor with which I rubbed my hands near raw until they were rid of the glowing purple spots, and hid the book back in the meat safe which I then purchased, after some haggling, for the suitably low price that rusting galvanised-iron meat safes commanded before they too, like all other old junk, came into fashion.

Exactly what my intentions were as I walked out into the light snowstorm, struggling with that cumbersome meat safe, I cannot to this day say. While I knew I would be able to spray the meat safe in a heritage colour and then flog it off as an antique sound-system cupboard for double what I paid, and while I was eventually to con a free filling from a dentist in return for the old women’s magazines to fill his waiting room, I had no idea what I was going to do with the Book of Fish.

To my shame, I must admit that at first I may have had the base impulse to rip out the many paintings of fish and frame them up and sell them to an antiquarian print dealer. But the more I read and reread the Book of Fish that cold night, the following night and the many nights thereafter, the less inclination I had to profit from it.

The story enchanted me, and I took to carrying the book with me everywhere, as if it were some powerful talisman, as if it contained some magic that might somehow convey or explain something fundamental to me. But what that fundamental thing was, or why it seemed to matter so much, I was at a loss then—and remain at a loss now—to explain.

All I can say with certainty is that when I took it to historians and bibliophiles and publishers for their opinion of its worth, thinking they might also delight in my discovery, it was sadly to discover that the enchantment was mine alone.

While all agreed that the Book of Fish was old, much of it—the story it purports to tell, the fishes it claims to represent, the convicts and guards and penal administrators it seeks to describe—seemed to concur with the known facts only long enough to enter with them into an argument. This bellicose book, it was put to me, was the insignificant if somewhat curious product of a particularly deranged mind of long ago.

When I managed to persuade the museum to run tests on the parchment and inks and paints, carbon date and even CAT scan the book page by page, they admitted all the materials and techniques seemed authentic to the period. Yet the story discredited itself so completely that, rather than agreeing to attest to the book as a genuine work of great historical interest, the museum’s experts instead congratulated me on the quality of my forgery and wished me all the best in my continuing work in tourism.

V

My last prospect lay with the eminent colonial historian Professor Roman de Silva, and my hopes rose for several days after I posted him the Book of Fish, then sank for as many weeks after waiting for a reply. Finally, on a drizzly Thursday afternoon, his secretary rang to say the professor would be available to meet for twenty minutes later that day in his university office.

I discovered there a man whose reputation seemed not just at odds, but in complete conflict, with his appearance. Professor Roman de Silva’s twitching movements and tiny, pot-gutted frame, his dyed jet-black hair swept up over his pinhead in an improbable teddy boy haircut, suggested an unfortunate cross between an Elvis doll and a nervous leghorn rooster.

It was clear that the Book of Fish stood in the dock accused, and the professor opened what was to amount to a withering case for the prosecution, determined never to allow our interview to degenerate into a conversation.

He turned his back to me, fossicked in a drawer and then—with a sudden movement meant to be dramatic, but which succeeded only in being awkward—he dropped a cast-iron ball and chain onto his desk. There was a tearing noise that sounded like wood fracturing, but Professor de Silva was already well into his act, and, a true pro, he wasn’t going to let this or anything else deter him.

‘So you see, Mr Hammet,’ he said.

I said nothing.

‘What do you see, Mr Hammet?’

I said nothing.

‘A ball and chain, Mr Hammet, is that what you see? A convict ball and chain, is it not?’

Wishing to be agreeable, I nodded.

‘No, Mr Hammet, you see nothing of the sort. A fraud, Mr Hammet, is what you see. A ball and chain made by ex-convicts in the late nineteenth century to sell to tourists visiting the Gothic horror land of the Port Arthur penal settlement is what you gaze upon. A tacky, fraudulent, tourist-souvenir type of fraud is what you see, Mr Hammet. A piece of kitsch that has nothing to do with history.’

He halted, balled the knuckle of a small index finger up into his hirsute nostrils, from which moist black hairs large enough to trap moths protruded, then resumed talking.

‘History, Mr Hammet, is what you cannot see. History has power. But a fake has none.’

I was impressed. Coming from where I did, it looked like the past of my own noble art. It also looked sellable. While I stood there wondering what Mr Hung’s skills at forging and blacksmithing were like, whether I should call the Conga and advise her of the potentially lucrative new line I had chanced upon, and what euphemisms I might deploy to communicate the erotic charge our American friends would inevitably find in such an item (‘Is there nothing that doesn’t mean sex to them?’ the Conga had one day asked, to which Mr Hung had replied, ‘People’), Professor Roman de Silva dropped—with what I felt to be an entire lack of respect—Gould’s Book of Fish next to the ball and chain.

‘And this, this is no better. An old fake, perhaps, Mr Hammet’—and here he fixed me with a sad, knowing gaze—‘though I am not even sure about my choice of adjective.’

He turned, put his hands in his pockets, and stared out of the window onto a carpark some storeys below for what seemed a very long time before speaking again.

‘But a fake nevertheless.’

And with his back to me, he continued rabbiting on in a manner, I suspected, honed on generations of suffering students, telling the window and the carpark how the penal colony described in the Book of Fish seemed, on the surface at least, the same as that which then existed on that island to which only the worst of all convicts were banished; how its location also accorded with what was known, marooned in a large harbour surrounded by the impenetrable wild lands of the western half of Van Diemen’s Land, an uncharted country depicted on maps of the day only as a baleful blankness colonial cartographers termed Transylvania.

Then he turned around to face me, brushing back his dandruff-confettied quiff for the hundredth time.

‘But while it is a matter of historical record that between 1820 and 1832 Sarah Island was the most dreaded place of punishment in the entire British Empire, almost nothing in the Book of Fish agrees with the known history of that island hell. Few of the names mentioned in your curious chronicle are to be found in any of the official documents that survive from that time, and those that do take on identities and histories entirely at odds with what is described in this . . . this sad pastiche.

‘And, if we care to examine the historical records,’ continued the professor, but I knew by then he hated the Book of Fish, that he looked for truth in facts and not in stories, that history for him was no more than the pretext for a rueful fatalism about the present, that a man with such hair was prone to a shallow nostalgia that would inevitably give way to a sense that life was as mundane as he was himself, ‘we discover that Sarah Island did not suffer the depredations of a tyrant ruler, nor for a time did it become a merchant port of such standing and independence that it became a separate trading nation, nor yet was it razed to the ground in an apocalyptic fire as recorded in the cataclysmic chronicle that is your Book of Fish.’ On and on he blathered, taking refuge in the one thing he felt lent him superiority: words.

He said that the Book of Fish might one day find a place in the inglorious, if not insubstantial, history of Australian literary frauds. ‘That one area of national letters,’ he observed, ‘in which Australia can rightly lay some claim to a global eminence.

‘It need not be added,’ he added, sly smile almost obscured by the limp quiff leaning over his face like a drunk about to vomit, ‘that if you were to publish it as a novel, the inevitable might happen: it could win literary prizes.’

The Book of Fish may have had its shortcomings—even if I wasn’t willing to admit to them—but it had never struck me as being sufficiently dull-witted and pompous to be mistaken for national literature. Taking the professor’s remark in the spirit of an ill-mannered jest at my expense, I concluded our meeting with a curt goodbye, took back the Book of Fish, and left.

VI

At first, i was partly persuaded by such arguments as I had heard, and agreed that the book must be some elaborate, mad deception. But as one who knows something of the game of deceit, who knows that swindling requires not delivering lies but confirming preconceptions, the book, if it was a fraud, made no sense, because none of it accorded with any expectation of what the past ought to be.

The book had grown into a puzzle I was now determined to solve. I trawled the Archives Office of Tasmania, whose neat, unremarkable urban shopfront belies the complete record of a totalitarian state that it houses. I discovered there little that was helpful, with the exception of the wise and venerable archivist, Mr Kim Pearce, with whom I took to drinking.

Beyond what Professor de Silva had termed ‘the undivinable oddities’ of the Book of Fish, there was the further problem of the identity of the chronicler himself, ‘the lacuna of lacunae’ as Professor de Silva had called it, a phrase that made as little sense to me as William Buelow Gould had to him.

In the convict records Mr Kim Pearce found several dead William Goulds, while introducing me to a living Willy Gold in the Hope and Anchor; an alcoholic watercolour painter of birds with a cleft palate (the painter, not the birds) at the Ocean Child; and Pete the publican in the snug—a small and comfy taproom—of the Crescent.

Only one of the historical (i.e., dead) William Goulds had a life that seemed to correspond in some ways with the author of the Book of Fish, sharing a similar criminal record and the same tattoo above his left breast—a red anchor with blue wings, wrapped around which was the legend: ‘LOVE AND LIBERTY’. It was this William Buelow Gould, a recidivist convict artist, who upon arriving in 1828 at the Sarah Island penal settlement, was charged with the specific duty of painting fish for the surgeon.

While such detail tallied with the life described in the Book of Fish, the historical Gould’s subsequent convict record suggests a life entirely at odds with that which had so captivated me. It sometimes seemed as if the author of the Book of Fish, the storyteller William Buelow Gould, had been born with a memory but neither experience nor history to account for it, and had spent forever after seeking to invent what didn’t exist in the curious belief that his imagination might become his experience, and thereby both explain and cure his problem of an inconsolable memory.

After such bafflement, imagine then my astonishment upon discovering in the hush of the Allport Library a second Book of Fish, attributed to the convict artist William Buelow Gould, which contained wondrous paintings identical to the Salamanca Book of Fish in all but one detail, a similarity so remarkable that I felt I was choking for want of air.

I took aside the kindly Mr Pearce, who had been so helpful, and explained why I had so loudly gasped.

I told him how I had discovered that there were clearly not one but two books of fish; how these two works that seemed so precisely to mirror each other were at once the same and yet fundamentally different. While one (the Allport Library Book of Fish) contained not a single written word, the other (the Salamanca Book of Fish) teemed with words as the ocean did fish, and these schools of words formed a chronicle that explained the curious genesis of the pictures. One book spoke with the authority of words and the other with the authority of silence, and it was impossible to tell which was the more mysterious.

‘Indeed,’ said Mr Kim Pearce, proffering without comment some Mylanta tablets, ‘their very mystery is heightened by each book’s distorted reflection of the other.’

I rushed home, grabbed my meat-safe edition from its hiding place behind the bathroom mirror, and retired to a nearby hotel once more to indulge myself in drink and fish.

And here, before I go any further, I must make mention of a second unusual attribute of the Book of Fish in addition to its self-illuminating cover, a remarkable quality that seemed to mirror life. I have mentioned how the book seemed never to really finish. But that is not the whole truth. Even now I hesitate before I write it down, this trait so peculiar as to be unbelievable—the refusal of its story to end.

Every time I opened the book a scrap of a paper with some revelation I had not hitherto read would fall out, or I would stumble across an annotation that I had somehow missed in my previous readings, or I would come upon two pages stuck together that I hadn’t noticed and which, when carefully teased apart, would contain a new element of the story that would force me to rethink the whole in an entirely changed light. In this way, each time I opened the Book of Fish what amounted to a new chapter miraculously appeared. That evening, sitting alone at the bar in the Republic—once the old Empire—was no different, except I knew, even in the decrepitude of my mindless passion, that by the very nature of its content what I was reading with growing horror was the last chapter I would ever read.

As I drew close to its conclusion the pages first grew damp beneath my fingers, then wet, and finally, as I felt my heart pounding, as my breathing sped up and I began to heave and pant, I had the inexplicable sense that I was now reading words written at the very bottom of the ocean.

In a state of utter disbelief I came to what I knew to be the ending. I realised that no more multi-coloured chapters would ever again so miraculously appear, and gazing in astonishment at the terrible tale of William Buelow Gould and his fish, I asked for an ouzo to steady my shaking hands, threw it down with a single, unsteady gulp and put it down on a Cascade beer towel, and then, still dazed, wandered off to the toilet.

When I returned it was to find the bar top had been cleared.

I felt my throat contracting and found it suddenly hard to breathe.

VII

There was noCascade beer towel.

There was no drained ouzo glass.

There was no . . . no Book of Fish!

I was trying to swallow but my mouth had gone dry. I was trying to stand up straight, but I was swaying, beset by a vertiginous fear. I was trying not to panic, but my heartbeat was a deafening roar, monstrous wave after wave of fear crashing on the ocean floor of my soul. Where I had left Gould’s Book of Fish there now remained nothing—nothing, that is, save a large, brackish puddle being mopped up by the barman with a sponge, which he then wrung into a sink.

Only now I realise that the Book of Fish was returning whence it came, that, paradoxically, just as the Book of Fish had ended for me, it was also beginning for others.

Only then nothing was clear. Worse still, no-one in the hotel that night, not the barman nor the several customers, had any recollection of the book ever having been there. A desolate horror, utter and huge as abandonment, gripped me.

Several harrowing, depressing weeks followed in which I pressed the police to no avail to fully investigate this obvious theft. I went back to the Salamanca junk shop in the hopeful, hopeless delusion that by some curious, temporal osmosis the book might have been reabsorbed into its past. I returned again and again to the Republic, spending hours searching under the bar, upending garbage bins, ejecting skateboards and their dozing street-kid owners from the skip out the back in my relentless search, confronting customers and staff over and over, until I was forcibly ejected and told never to return. I spent long hours staring at the putrid outfall of sewage drains under the delusion that the book might there metamorphose.

But after some months, I had to face the awful truth.

The Book of Fish, with its myriad wonders and its horrific, unfolding and ever-growing tale, was gone. I had lost something fundamental and had acquired in its place a curious infection: the terrible contagion of an unrequited love.

VIII

‘Travel? Hobbies?’ asked Doctor Bundy in his cotton-wadding voice that I had grown to hate along with everything else about Doctor Bundy in the five minutes since I first entered his surgery. As I sat back up and put my shirt on he told me that he could find no problem with my health, that perhaps all I needed was some new—some other—interest. On and on he went—had I thought about joining a sporting club? A men’s support group?

I felt the same sensation of breathlessness that had seized me in the Allport Library and then grabbed me in the pub the fateful evening the Book of Fish disappeared. I rushed out of his consulting room. Given that Doctor Bundy refused to countenance the fact of my illness, it seemed not unreasonable for me to refuse to countenance the worth of his remedies. In any case I had no money to travel, no desire to take up a hobby, and a strong aversion to the public humiliations implicit in triathlons or being made to bear-hug sweating New Age dentists in wigwams as they solemnly ran feathers over each other, all the while blubbering about never having known their fathers.

So eating continued to make me nauseous, I spent my nights staring into an ocean of darkness I could never enter, and my waking hours, which were infinite, filled with nightmares of sea creatures, and for a long time I remained inexplicably ill.

In the way they so often do, other tragedies clustered. Great Aunt Maisie died of salmonella poisoning. I spent long hours at her graveside. The book, I came to think, was not unlike those frozen quiches she had once with such gusto produced from her chest freezer with a use-by date stamped for two decades previous, merely waiting for the miracle of the microwave to resurrect. The book was the North Hobart football ground waiting for a few drops of Lourdes holy water and memories of absent love. The book, I began to suspect, was waiting for me.

Perhaps it was in this way my illness took on the form of a mission. Or perhaps only my joy in the glorious wonder of all that Gould wrote and painted explains my subsequent decision to rewrite the Book of Fish, a book in which there is no popular interest nor academic justification nor financial reward, nothing really, save the folly of a sorry passion.

From memories, good and bad, reliable and unreliable; by using bad transcriptions that I had made, some of complete sections, others only brief notes describing lengthy tracts of the book; and by the useful expedient of reproducing the pictures from the wordless Allport Book of Fish, I set about my forlorn task.

Maybe Mr Hung with his shrine to Victor Hugo is right: to make a book, even one so inadequate as this wretched copy you now read, is to learn that the only appropriate feeling to those who live within its pages is love. Perhaps reading and writing books is one of the last defences human dignity has left, because in the end they remind us of what God once reminded us before He too evaporated in this age of relentless humiliations—that we are more than ourselves; that we have souls. And more, moreover.

Or perhaps not.

Because it clearly was too big a burden for God, this business about reminding people of being other than hungry dust, and really the only wonder is that He persevered with it for so long before giving up. Not that I am unsympathetic—I’ve often felt the same weary disgust with my own rude creations—but I neither expect nor wish the book to succeed where He failed. My desire was only ever to make a vessel—however crude—in which all Gould’s fish might be returned to the sea.

But I must confess to a growing ache within, for these days I am no longer sure what is memory and what is revelation. How faithful the story you are about to read is to the original is a bone of contention with the few people I had allowed to read the original Book of Fish. The Conga—unreliable, granted—maintains there is no difference. Or at least no difference that matters. And certainly, the book you will read is the same as the book I remember reading, and I have tried to be true both to the wonder of that reading and to the extraordinary world that was Gould’s.

Though I had hoped he might, Mr Hung doesn’t know. On that wet afternoon when we sat down in front of the log fire in the Hope & Anchor and I put these troubling questions to him—the only person I know who knew anything about books—thinking he might say something that would quell my ever more unruly heart, Mr Hung quaintly ventured the suggestion that books and their authors are indivisible, and—in what I thought a somewhat obscure explanation—told (between Pernods, another curious legacy of the French) the story of how Flaubert, pestered to declare who was the model for Madame Bovary, finally cried out in what Mr Hung claimed to be both exasperation and elation—‘Madame Bovary, cest moi!’

After this incomprehensible anecdote which left Mr Hung exultant, and me and the Conga—knowing neither French nor literature, and even after Mr Hung’s subsequent translation (‘Madame Bovary is me!’)—little the wiser, the Conga declared she didn’t know either.

‘Perhaps,’ I venture, ‘de Silva is right. It was just a fraud.’

‘Fuck de Silva,’ says the Conga, her face flushing with drink and anger, ‘fuck them all!’

‘Sure,’ I say, ‘sure.’

But in truth I am unsure.

I had begun with the comforting conclusion that books are the tongue of divine wisdom, and had ended only with the thin hunch that all books are grand follies, destined forever to be misunderstood.

Mr. Hung says that a book at its beginning may be a new way of understanding life—an original universe—but it is soon enough no more than a mere footnote in the history of writing, overpraised by the sycophantic, despised by the contemporary, and read by neither. Their fate is hard, their destiny absurd. If readers ignore them they die, and if granted the thumbs-up of posterity they are destined forever to be misconstrued, their authors transformed first into gods and then, inevitably, unless they are Victor Hugo, into devils.

And with that, he drains a final Pernod and leaves.

Afterwards the Conga comes over all amorous, stands close by me, leans on me so we pitch and toss like a single boat in a wild sea, furtively reaches beneath my groin and tugs on my balls like they are the cord to a klaxon horn.

Poop—poop!

We end up in her bed together, faces and bodies crisscrossed by the shadows thrown by stacks of unsold Vietnamese Shaker furniture made by a refugee who suspects God to be Victor Hugo and Emma Bovary to be Gustave Flaubert, and her passion evaporates in an instant.

Her eyes glaze.

Her lips quiver.

‘Who are you?’ she suddenly cries aloud. ‘Who?’

And she is frightened, so terribly frightened, and she is seeing someone else, but who it is I have no way of knowing. For her body is abruptly dead and exists only in the most dreadful state of subjugation, and I, despicably, continue for a short time, before my own feeling of horror overwhelms even my overwhelming animal desire and I withdraw.

‘Why are you going?’ the Conga cries out, but now her voice is different, and I realise she is back from wherever she has been.

‘Don’t go, come back here,’ the Conga says and she opens her arms to me, and relieved, I remount. And then once more her eyes glaze, her body deadens, and she cries out again and again, ‘Who are you? Who are you? Who are you?’ and she is crying and this time I simply want to escape this strange circle, and I get up and hastily pull on my clothes, and the Conga all the time saying, as nice as pie, genuinely upset, ‘But why? Why are you going?’ And I am gone because I have no furniture to offer her that might give solace, no fake chairs or tables to trade for her guilty sadnesses, because I cannot answer either for her or for me who I am or who she is, far less what this Book of Fish is about.

How can I tell her that late of a night when melancholia seems to fall with the evening dew, I am taken of the strong fancy that for me alone William Buelow Gould was born: that he made his life for me and me this Book of Fish for him; that our destiny was always one?

Because, you see, it sometimes seems so elusive, this book, a series of veils, each of which must be lifted and parted to reveal only another of its kind, to arrive finally at emptiness, a lack of words, at the sound of the sea, of the great Indian Ocean through which I see in my mind’s eye Gould now advancing towards Sarah Island, now receding; that sound, that sight, slowly pulsing in and out, in and out.

I fell into an old russet armchair in the Conga’s dark lounge room, exhausted from the shameful descent my life had become, and before I knew it, had fallen fast asleep, with a single, insistent question playing like an endless loop deep in my mind.

Who am I . . . ? it was asking. Who am I . . . ?

IX

I sought the answer to what for me was a growing enigma by taking refuge in the one place left to the dumb and outdated, the ill and aged and unwanted: the old pubs with their new blinking pokies and that dull stuttering sound peculiar to those souls lost within, spinning away to some outer universe that presages death.

In the course of my journeys through this flickering netherworld I asked any who were for the moment not gambling and whose problems seemed not as great as mine, to come drink with me and tell me what they made of my story and my pictures—photographic reproductions of the pictures from the Allport Book of Fish, tatty with wear—that I would then lay out on the bar to accompany my tale. And I would ask them questions.

A small number would think the pictures rough but not badly done, and the story—as I paraphrased it—entirely mad. Having acquired from the academics I had met in the course of my enquiries the habit of pointless argument, I would try to persuade my bar colleagues that perhaps in madness lies the truth, or in truth madness.

‘Who was your mother and what secrets did she whisper in your infant ear?’ I would demand of them. ‘Was she a fish?’ I would start yelling. ‘Was she?’

‘The world was stupid in the first place,’ someone said, not in reply but in derision, ‘and it’s only grown stupider ever since.’

‘Travel with me into time,’ I would cry out in answer to such, ‘you dull mullet-eyed men and gurnard-gilded women! Journey with me far from this land of sodden beer mats and amnesiac entertainments to where your heart may be found! Where is the distant land which your soul wishes to traverse? What is it that beats in your belly and troubles your dreams? What shade of the past is it that torments you so? What manner of sea creature are you?’

But to tell the truth, they really weren’t much help at all. They gave me no answer to any of my million and one questions. They took to shunning me even before I opened my mouth, scurrying past to spend the rest of their termination payouts and disability pensions and unemployment cheques, filling their polystyrene Coke cups to the brim with change for the pokies, and then sitting in front of the screens mesmerised at how their hard fates could be so precisely rendered in the perfect image of those spinning wheels.

The few who showed any interest would revile me and laugh at my observation that the meanings of Gould’s Book of Fish were infinite, while others who knew me would tell me to go back to fooling Americans rather than fooling myself. A stranger jobbed me in the mug so hard that I fell off my chair. Everyone around only laughed as he then poured my beer over me, singing, ‘Swim, little fishie! Swim back to the sea!’ all laughing their sad heads off, all, that is, with the exception of Mr Hung, who had just walked in.

Mr Hung put his hands under my arms and dragged me outside. As I lay groaning on the wet bitumen pavement, he felt inside my coat and, finding my wallet, emptied it of cash. He stood up, promised to return, Victor Hugo willing, with enough in winnings to start a fake painting racket. He dissolved into the stuttering neon inside.

To those who continued swimming past my prostrate form into the gaming bar my pictures of silver dories and stargazers were, I realised, useless; as pointless to them as a row of two lemons and a pineapple, as disappointing as a busted flush. All the fish lacked in their eyes was the sign across their images announcing our mutual destiny in blinking letters—

‘GAME OVER.’

X

After Mr. Hung had lost all my money he came back out, promised he would repay me soon, and took me to his Zinc Company home in Lutana. We entered quietly, as his wife and children were asleep. He disappeared into his kitchen to cook us some soup and left me in his small lounge-cum-dining room.

In a corner was a shrine to Victor Hugo. On a green velvet cloth there was propped a red plastic frame housing a photocopied lithograph of the great man, arrayed around whom were two unlit candles, four burnt incense sticks, several paperback novels, and some puckering apricots.

Next to the shrine sat an aquarium, in which Mr Hung kept a large pot-bellied seahorse and a similar creature, a good foot long, covered in delicate leaf-like fins, which he later told me was a weedy seadragon, both like pictures I had seen in the Book of Fish. I gazed on these alien beings that seemed to float so serenely.

Bony-ringed, tube-snouted, the pot-bellied seahorse’s small fins fluttered as furiously as a blushing debutante’s fan. He had pectoral fins on his cheeks with which he steered himself, a combination of sideburn and steering wheel. Mr. Hung appeared next to me with two bowls of steaming soup. As he set these down on the table, he explained to me the seahorse’s capacity to transform, how the male gave birth to hundreds of tiny seahorses that it had incubated in a brood pouch.

And then, as if on cue, the seahorse began to give birth. I watched, mesmerised, as before my eyes he jerked back and forth in an anxious pumping movement, and every minute or so another one or two black baby seahorses would shoot out of a vent in the centre of his swollen belly as he painfully flexed: tiny little black sticks which would immediately start swimming, with only their large eyes and long tube snouts recognisable, so many rising and falling curlicues. They were like Gould’s lost words, and I felt a little like the poor seahorse at the end of his prolonged labour, his formerly swollen belly now flaccid, was exhausted with all his awkward motions.

My gaze turned to the weedy seadragon, which was, I had to agree with Mr. Hung, a magnificent creature. The weedy seadragon swam horizontally like a fish, rather than vertically like the seahorse, but like the seahorse its movements were beautiful: it hovered up and down, forwards and sideways, like a hovercraft crossed with a helicopter, a jump-jet in rich mufti. Its luminous colouring was exquisite—its trunk pinkish red, purple blacks and silver blues spotted with yellow dots, billowing around which were its mauve leaves. Yet there was a serene grace about it that was also the oddest melancholy. As well as wonder, it shimmered sadness.

I was not then a weedy seadragon, and so I could not sense its terrible imprisonment, which was endless. I fancied I understood its horrific calmness; only a lifetime later would I truly comprehend the reason for such: that sense that all good and all evil are equally inescapable. Yet understanding all, the weedy seadragon seemed troubled not at not being understood.

I put my face to the glass, stared closer, trying to fathom its descending mystery. Then I imagined the weedy seadragon’s beauty arose out of some evolutionary necessity; to attract mates possibly, or to merge with colourful reefs. Now I know beauty is life’s revolt against life, that the seadragon was that most perfect of things, a song of itself.

There was a moment of transition that was abrupt: enlightenment is too smooth a word for the jolt I felt. It was a dream, but only much later was I to realise that there would be no awakening. With that long snout the seadragon was touching the other side of the glass to which my face was pressed. Its astonishing eyes rotated independently of each other, yet both were at different angles focused on me. What was it trying to tell me? Nothing? Something? I felt accused, guilty. I began whispering at the glass, hissing almost angrily. Was it asking of me questions to which I had no answer? Or was the seadragon saying to me in some diaphanous communication beyond words: I shall be you.

And shall I, I wondered, be you?

Other than the slightest movements of its leafy fins, I know the seadragon did not move while I muttered away, just stared out and through me in the most awful, knowing way with its unruly peepers.

I stopped talking.

Perhaps I stared too long.

Whatever, there was a momentary sense that was both a sickening vertigo and a wild freedom. I was without weight, support, structure; I was falling, tumbling, passing through glass and through water into that seadragon’s eye while that seadragon was passing into me, and then I was looking out at that bedraggled man staring in at me, that man who would, I now had the vanity of hoping, finally tell my story.

Excerpted from GOULD'S BOOK OF FISH: A Novel in Twelve Fish © Copyright 2002 by Richard Flanagan. Reprinted with permission by Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.

Gould's Book of Fish: A Novel in Twelve Fish

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- paperback: 416 pages

- Publisher: Grove Press

- ISBN-10: 0802139590

- ISBN-13: 9780802139597