Excerpt

Excerpt

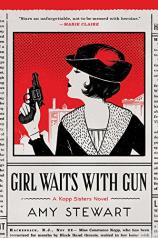

Girl Waits With Gun: A Kopp Sisters Novel

1

Our troubles began in the summer of 1914, the year I turned thirty-five. The Archduke of Austria had just been assassinated, the Mexicans were revolting, and absolutely nothing was happening at our house, which explains why all three of us were riding to Paterson on the most trivial of errands. Never had a larger committee been convened to make a decision about the purchase of mustard powder and the replacement of a claw hammer whose handle had split from age and misuse.

Against my better judgment I allowed Fleurette to drive. Norma was reading to us from the newspaper as she always did.

“‘Man’s Trousers Cause Death,’ ” Norma called out.

“It doesn’t say that.” Fleurette snorted and turned around to get a look at the paper. The reins slid out of her hands.

“It does,” Norma said. “It says that a Teamster was in the habit of hanging his trousers over the gas jet at night but, being under the influence of liquor, didn’t notice that the trousers smothered the flame.”

“Then he died of gas poisoning, not of trousers.”

“Well, the trousers —”

The low, goosey cry of a horn interrupted Norma. I turned just in time to see a black motor car barreling toward us, tearing down Hamilton and picking up speed as it crossed the intersection. Fleurette jumped up on the footboard to wave the driver off.

“Get down!” I shouted, but it was too late.

The automobile hit us broadside, its brakes shrieking. The sound of our buggy shattering was like a firecracker going off in our ears. We tumbled over in a mess of splintered wood and bent metal. Our harness mare, Dolley, faltered and went down with us. She let out a high scream, the likes of which I had never heard from a horse.

Something heavy pinned my shoulder. I reached around and found it was Norma’s foot. “You’re standing on me!”

“I am not. I can’t even see you,” Norma said.

Our wagon rocked back and forth as the motor car reversed its engine and broke free of the wreckage. I was trapped under the overturned rear seat. It was as dark as a coffin, but there was a dim shape below me that I believed to be Fleurette’s arm. I didn’t dare move for fear of crushing her.

From the clamor around us, I gathered that someone was trying to rock the wagon and get it upright. “Don’t!” I yelled. “My sister’s under the wheel.” If the wheel started to turn, she’d be caught up in it.

A pair of arms the size of tree branches reached into the rubble and got hold of Norma. “Take your hands off me!” she shouted.

“He’s trying to get you out,” I called. With a grunt, she accepted the man’s help. Norma hated to be manhandled.

Once she was free, I climbed out behind her. The man attached to the enormous arms wore an apron covered in blood. For one terrible second, I thought it was ours, then I realized he was a butcher at the meat counter across the street.

He wasn’t the only one who had come running out when the automobile hit us. We were surrounded by store clerks, locksmiths, grocers, delivery boys, shoppers — in fact, most of the stores on Market Street had emptied, their occupants drawn to the spectacle we were now providing. Most of them watched from the sidewalk, but a sizable contingent surrounded the motor car, preventing its escape.

The butcher and a couple of men from the print shop, their hands black with ink, helped us raise the wagon just enough to allow Fleurette to slide clear of the wheel. As we lifted the broken panels off her, Fleurette stared up at us with wild dark eyes. She wore a dress sheathed in pink taffeta. Against the dusty road she looked like a trampled bed of roses.

“Don’t move,” I whispered, bending over her, but she got her arms underneath herself and sat up.

“No, no, no,” said one of the printers. “We’ll call for a doctor.”

I looked up at the men standing in a circle around us.

“She’ll be fine,” I said, sliding a hand over her ankle. “Go on.” Some of those men looked a little too eager to help with the examination of Fleurette’s legs. They shuffled off to help two livery drivers, who had disembarked from their own wagons to tend to our mare.

They freed her from the harness and she struggled to stand. The poor creature groaned and tossed her head and blew steam from her nostrils. The drivers fed her something from their pockets and that seemed to settle her.

I gave Fleurette’s calf a squeeze. She howled and jerked away from me.

“Is it broken?” she asked.

I couldn’t say. “Try to move it.”

She screwed her face into a knot, held her breath, and gingerly bent one leg and then the other. When she was finished she let her breath go all at once and looked up at me, panting.

“That’s good,” I said. “Now move your ankles and your toes.”

We both looked down at her feet. She was wearing the most ridiculous white calfskin boots with pink ribbons for laces.

“Are they all right?” she asked.

I put my hand on her back to steady her. “Just try to move them. First your ankle.”

“I meant the boots.”

That’s when I knew Fleurette would survive. I unlaced the boots and promised to look after them. A much larger crowd had gathered, and Fleurette wiggled her pale-stockinged toes for her new audience.

“You’ll have quite a bruise tomorrow, miss,” said a lady behind us.

The seat that had trapped me a few moments ago was resting on the ground. I helped Fleurette into it and took another look at her legs. Her stockings were torn and she was scratched and bruised, but not broken to bits as I’d feared. I offered my handkerchief to press against one long and shallow cut along her ankle, but she’d already lost interest in her own injuries.

“Look at Norma,” she whispered with a wicked little smile. My sister had planted herself directly in the path of the motor car to prevent the men from driving away. She did make a comical sight, a small but stocky figure in her split riding skirt of drab cotton. Norma had the broad Slavic face and thick nose of our father and our mother’s sour disposition. Her mouth was set in a permanent frown and she looked on everyone with suspicion. She stared down the driver of the motor car with the kind of flat-footed resolve that came naturally to her in times of calamity.

The automobilist was a short but solidly built young man who had an overfed look about him, hinting at a privileged life. He would have been handsome if not for an indolent and spoiled aspect about his eyes and the tough set of his mouth, which suggested he was accustomed to getting his way. His face was puffy and red from the heat, but also, I suspected, from a habit of putting away a quart of beer at breakfast and a bottle of wine at night. He was dressed exceedingly well, in striped linen trousers, a silk waistcoat with polished brass buttons, and a tie as red as the blood seeping through Fleurette’s stockings.

His companions tumbled out of the car and gathered around him as if standing guard. They wore the plain broadcloth suits of working men and carried themselves like rats who weren’t accustomed to being spotted in the daylight. Each of them was unkempt and unshaven, and a few kept their hands in their pockets in a manner that suggested they might be reaching for their knives. I couldn’t imagine where this gang of ruffians had been off to in such a hurry, but I was already beginning to regret that we had been the ones to get in their way.

Girl Waits With Gun: A Kopp Sisters Novel

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction, Historical Mystery, Mystery

- paperback: 448 pages

- Publisher: Mariner Books

- ISBN-10: 0544800834

- ISBN-13: 9780544800830