Excerpt

Excerpt

When the Killing's Done

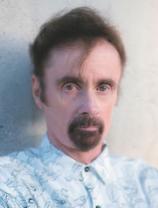

THE WRECK OF THE BEVERLY B.

T. Coraghessan Boyle

Picture her there in the pinched little galley where you could

barely stand up without cracking your head, her right hand raw and

stinging still from the scald of the coffee she'd dutifully --- and

foolishly --- tried to make so they could have something to keep

them going, a good sport, always a good sport though she'd woken up

vomiting in her berth not half an hour ago. She was wearing an

oversized cableknit sweater she'd fished out of her husband's

locker because the cabin was so cold, and every fiber of it seemed

to chafe her skin as if she'd been flayed raw while she slept. She

hadn't brushed her hair. Or her teeth. She was having trouble

keeping her balance, wondering if it was always this rough out

here, but she was afraid to ask Till about it, or Warren either.

She didn't know the first thing about handling a boat or riding out

a heavy sea or even reading a chart, as the two of them had been

more than happy to remind her every chance they got, and Till told

her she should just settle in and enjoy the ride. Her place was in

the kitchen. Or rather, the galley. She was going to clean the fish

and fry them and when the sun came out --- if it came out --- she

would spread a towel on top of the cabin and rub a mixture of baby

oil and iodine on her legs, lie back, shut her eyes and bask till

they were a nice uniform brown.

It was only now, the boat pitching and rolling and her right

hand vibrant with pain, that she realized her feet were wet, her

socks clammy and clinging and her new white tennis shoes gone a

dark saturate gray. And why were her feet wet? Because there was

water on the galley deck. Not coffee --- she'd swabbed that up as

best she could with a rag --- but water. Salt water. A thin

bellying sheet of it riding toward her and then jerking back as the

boat pitched into another trough. She would have had to sit heavily

then, the bench rising up to meet her while she clung to the

tabletop with both hands, as helpless in that moment as if she were

strapped into one of those lurching rides at the amusement park

Till seemed to love so much but that only made her feel as if her

stomach had swallowed itself up like in that cartoon of the snake

feeding its tail into its own jaws.

The cuffs of her blue jeans were wet, instantly wet, the boat

riding up again and the water shooting back at her, more of it now,

a shock of cold up to her ankles. She tried to call out, but her

throat squeezed shut. The water fled down the length of the deck

and came back again, deeper, colder. Do something! she

told herself. Get up. Move! Fighting down her nausea, she

pulled herself around the table hand over hand so she could peer up

the three steps to where Till sat at the helm, his bad arm rigid as

a stick, while Warren, his brother Warren, the ex-Marine, bossy,

know-it-all, shoved savagely at him, fighting him for the wheel.

She wanted to warn them, wanted to betray the water in the galley

so they could do something about it, so they could stop it, fix it,

put things to right, but Warren was shouting, every vein standing

out in his neck and the spray exploding over the stern behind him

like the whipping tail of an underwater comet. "Goddamn you,

goddamn you to hell! Keep the bow to the fucking waves!" The ship

lurched sideways, shuddering down the length of it. "You want to

see the whole goddamn shitbox go down . . . ?"

The month was March, the year 1946. Seaman First Class Tilden

Matthew Boyd was six months home from the war in the Pacific that

had left him with a withered right arm shorn of meat above the

elbow, nothing there but a scar like a seared omelet wrapped around

the bone. Beverly, young and hopeful and with hair as dark and

abundant as any combed-out movie star's, broke a bottle over the

bow of the Beverly B. while Till, restored to her from the

vortex of the war in a miraculous dispensation more actual and

solid than all the cathedrals in the world, sat at the helm and the

gulls dipped overhead and the clouds swept in on a northwesterly

breeze to chase the sun over the water. Beverly was happy because

Till was happy and they ate their sandwiches and drank the cheap

champagne out of paper cups in the cabin because the wind was stiff

and the chop wintry and white-capped. Warren was there too that

first day, the day of the launching, a walking Dictaphone of

unasked-for advice, ringing clichés and long-winded criticism.

But he drank the champagne and he showed up two weekends in a row

to help Till tinker with the engines and install the teak cabinets

and fiddle rails Till had made in the garage of their rented house

that needed paint and windowscreens for the mosquitoes and

drainpipes to keep the winter rains from shearing off the roof and

dousing anybody standing at the front door with a key in her hand

and a load of groceries in both her aching arms. But Till had no

desire to fix the house --- it didn't belong to them anyway. The

Beverly B., though --- that was a different story.

She was a sleek twenty-eight-foot all-wood cabin cruiser,

solid-built, with butternut bulkheads and teak trim throughout, a

real beauty, but she'd been dry-docked and neglected during the

war, from which her owner, a Navy man, had never returned. Till

spotted the boat listing into the weeds at the back of the boatyard

and had tracked down the Navy man's quietly grieving parents ---

their boy had been burned to death in a slick of oil after a

kamikaze pilot steered himself into the St. Lo during the

battle of Leyte Gulf --- in whose living room he'd sat with his hat

perched on one knee while they fingered the photographs and medals

that were their son's last relics. He sat there for two full hours,

sipping tepid Lipton's tea with a bitter slice of lemon slowly

revolving atop it, before he mentioned the boat, and when he did

finally mention it they both stared at him as if he'd crawled up

out of the pages of the family album to perch there on the velour

cushions of the maplewood couch in the shrouded and barely-lit

living room they'd inhabited like ghosts since before they could

remember. The mother --- she must have been in her fifties, stout,

but with the delicate wrists and ankles of a girl and a face

infused with outrage and grief in equal measures --- threw back her

head and all but yodeled, "That old thing?" Then she looked to her

husband and dropped her voice. "I don't guess Roger'll be needing

it now, will he?"

Over the course of the fall and winter, Till had devoted himself

to the task of refitting that boat, haunting the boatyard and the

chandlery and fooling with the engines until he was so smudged with

oil Beverly told anybody who wanted to listen that he half the time

looked like he was rigged out in blackface for some old-timey

minstrel show. Her joke. Till in blackface. And she used it on Mrs.

Viola down at the market and on Warren and the girl he was seeing,

Sandra, with the prim mouth and the sweaters she wore so tight you

could see every line of her brassiere, straps and cups and all.

Careful, that was what Till was. Careful and precise and unerring.

He never mentioned it, never complained, but he'd given his right

arm for his country and he was determined to keep the left one for

himself. And for her. For her, above all.

He had to learn how to make it do the work of his right arm and

wrist and hand, punching tickets for the Santa Monica Boulevard

line while people looked on impatiently and tried to be polite out

of a kind of grudging recognition, the dead hand clenching the

ticket stub and the newly dominant one doing the punching, and he

learned to use that hand to fold his paycheck over once and present

it to her like a ticket itself, a ticket to a moveable feast to

which she and she alone was invited. At night, late, after supper

and the radio, he'd let the hand play over her nakedness as if it

knew no impediment, and that was all right, that was as good as it

was going to get, because he was left-handed now and always would

be till the day he was gone. And when they launched the Beverly

B., he was as gentle and cautious with his boat as he was with

her in their marriage bed, the right arm swinging stiffly into play

when the wheel revolved under pressure of the left, and the first

few times they never took her out of sight of the harbor. Till said

he wanted to get a feel for her, wanted to break her in, listen to

what the twin Chrysler engines had to say when he pushed the

throttle all the way forward and watched the tachometer climb to

2,800 RPM.

Then came that Friday evening late in March when she and Till

and Warren motored out of the harbor on a course for the nearest of

the northern Channel Islands, for Anacapa and the big one beyond

it, Santa Cruz, because that was where the fish were, the lingcod

as long as your arm, the abalone you only had to pluck off the

rocks and more plentiful than the rocks themselves, the lobsters so

accommodating they'd crawl right up the anchor line and dunk

themselves in the pot. A man at work had told Till all about it.

Anybody could go out to Catalina --- hell, everybody did go out

there, day trippers and Saturday sailors and the rest --- but if

you wanted something akin to virgin territory, the northern

islands, up off of Oxnard and Santa Barbara, that was the place to

go. They'd brought along the two biggest ice chests she'd been able

to find at Sears & Roebuck, both of them bristling with the

dark slender necks of the beer bottles Warren assured her would

have vanished by the time all those fish fillets and boiled

lobsters were ready to nestle down there between their sheets of

ice for a nice long sleep on the way home.

"We'll have fish for a week, a week at least," Till kept saying.

"And when they're gone we can just go out again and again after

that." He gave her a look. He was at the helm, the weather calm,

the evening haze with its opalescent tinge clinging to the water

out there before them and the harbor sliding into the wake behind,

the beer in his hand barely an encumbrance as he perched there like

some sea captain out of a Jack London story. "Which," he said,

knowing how sensitive she'd been on the subject of sinking money

into the boat, "should cut our grocery bill by half, half at

least."

She'd made sandwiches at home --- liverwurst on white with

plenty of mustard and mayo, ham on rye, tuna fish salad --- and

when they settled down in the cabin to take big hungry bites out of

them and wet their throats with the beer that was so cold it went

down like mountain spring water, it was as if they'd fallen off the

edge of the world. After dinner she'd sat out on the stern deck for

a long while, the air sweet and unalloyed, everything still but for

the steady thrum of the engines that was like the working of a sure

steady heart, the heart at the center of the Beverly B.,

unflagging and assured. There were dolphins, aggregations of them,

silvered and pinked as they sluiced through the water and raced the

hull to feel the electricity of it. They seemed to be grinning at

her, welcoming her, as happy in their element as she was in hers.

And what was that story she'd read --- was it in the newspaper or

Reader's Digest? The one about the boy on his surfboard

taken out to sea on a riptide and the sharks coming for him till

the dolphins showed up grinning and drove them off because dolphins

are mammals, warm-blooded in the cold sea, and they despise the

sharks as the cold agents of death they are. Did they nose the

boy's surfboard past the riptide and into shore, guiding him all

the way like guardian angels? Maybe, maybe they did.

The last of the sun was tangled up in the mist ahead of them,

due west and west the sun doth sink, the lines of a nursery rhyme

scattered in her head. She lifted her feet to the varnished rail

and studied her toes, seeing where the polish had faded and

thinking to refresh it when she had the chance, when the boys were

fishing in the morning and she was stretched out in the sun without

a care in the world. The engines hummed. A whole squadron of dark

beating birds shot up off the water and looped back again as if

they were attached to a flexible band, and not a one of them made

the slightest sound. She lit a cigarette, the wind in her hair, and

watched her husband through the newly washed windows as he held

lightly to the wheel while his brother sat on the bench beside him,

talking, always talking, but in dumb show now because the cabin

door was shut and she couldn't hear a word.

She finished her cigarette and let the butt launch itself into

the wind on a tail of red streamers. It was getting chilly, the sky

darkening, closing round them like a lid set to an infinite iron

pot. One more minute and she'd go in and listen to them talk, men's

talk, about the pie in the sky, the fish in the sea, the

carburetors and open-faced reels and lathes and varnishes and tools

and brushes and calibrators that made them men, and she'd open

another beer too, a celebratory last beer to top off the

celebratory three --- or was it four? --- she'd already had. It was

then, just as she was about to rise, that the sea suddenly broke

open like a dark spewing mouth and spat something at her, a

hurtling shadowy missile that ran straight for her face till she

snapped her head aside and it crashed with a reverberant wet

thumping slap into the glass of the cabin door and both men wheeled

round to see what it was.

She let out a scream. She couldn't help herself. This thing was

alive and flapping there at her feet like some sort of sea bat, as

long as her forearm, shivering now and springing up like a jack in

the box to fall back again and flap itself across the deck on the

tripod of its wings and tail. Wings? It was --- it was a fish,

wasn't it? But here was Till, Warren bundled behind him, his face

finding the middle passage between alarm and amusement, and he was

stepping on the thing, slamming his foot down, hard, bending

quickly to snatch the slick wet length of it up off the deck and

hold it out to her like an offering in the grip of his good hand.

"God, Bev, you gave me a scare --- I thought you'd gone and pitched

overboard with that scream."

Warren was laughing behind the sheen of merriment in his eyes.

The boat steadied and kept on. "This calls for a toast," he

shouted, raising the beer bottle that was perpetual with him.

"Bev's caught the first fish!"

She was over her fright. But it wasn't fright --- she wasn't one

of those clinging weepy women like you saw in the movies. She'd

just been startled, that was all. And who wouldn't have been, what

with this thing, blue as gunmetal above and silver as a stack of

coins below, coming at her like a torpedo with no warning at all?

"Jesus lord," she said, "what is it?"

Till held it out for her to take in her own hand, and she was

smiling now, on the verge of a good laugh, a shared laugh, but she

backed up against the rail while the sky closed in and the wake

unraveled behind her. "Haven't you ever seen a flying fish before?"

Till was saying. He made a clucking sound with his tongue.

"Where've you been keeping yourself, woman?" he said, ribbing her.

"This is no kitchen or sitting room or steam-heated parlor. You're

out in the wide world now."

"A toast!" Warren crowed. "To Bev! A-number-one fisherwoman!"

And he was about to tip back the bottle when she took hold of his

forearm, her hair whipping in the breeze. "Well then," she said,

"in that case, I guess you're just going to have to get me another

beer."

She woke dry-mouthed, a faint rising vapor lifting somewhere

behind her eyes, as if her head had been pumped full of helium

while she slept. In the berth across from her, snug under the bow

as it skipped and hovered and rapped gently against the cushion of

the waves, Till was asleep, his face turned to the wall which

wasn't a wall but the planking of the hull of the ship that held

them suspended over a black chasm of water. Below her, down deep,

there were things immense and minute, whales, copepods, sharks and

sardines, crabs infinite --- the bottom alive with them in their

horny chitinous legions, the crabs that tore the flesh from the

drowned things and fed the scraps into the shearing miniature

shredders of their mouths. All this came to her in the instant of

waking, without confusion or dislocation --- she wasn't in the

double bed they were still making payments on or stretched out on

the narrow mattress in the spare room at her parents' house where

she'd waited through a thousand hollow echoing nights for Till to

come home and reclaim her. She was at sea. She knew the rocking of

the boat as intimately now as if she'd never known anything else,

felt the muted drone of the engines deep inside her, in the thump

of her heart and the pulse of her blood. At sea. She was at

sea.

She sat up. A shaft of moonlight cut through the cabin behind

her, slicing the table in two. Beyond that, a dark well of shadow,

and beyond the shadow the steps to the bridge and the green glow of

the controls where Warren, with his bunched muscles and engraved

mouth, sat piloting them through the night. She needed --- urgently

--- to use the lavatory. The head, that is. And water --- she

needed a glass of water from the tap in the head that was attached

to the forty-gallon tank in the hold that Till had made such a fuss

about because you couldn't waste water, not at sea, where you never

knew when you were going to get more. It had got to the point where

she was almost afraid to turn on the tap for fear of losing a

single precious drop. What was that poem from high school? "Water,

water, every where/Nor any drop to drink."

The mariner, that was it. The ancient mariner. And he just had

to go and kill that bird, didn't he? The albatross. And what was an

albatross, anyway? Something big and white, judging from the

illustration in the book she'd got out of the library. Like a

dinosaur, maybe, only not as big. Probably extinct now. But if

albatrosses weren't extinct and one of them came flapping down out

of the sky and perched itself on the bow right this minute, she

wouldn't even think about shooting it. Uh, uh. Not her. For one

thing, she didn't have a gun, and even if she had one she wouldn't

know how to use it, but then that wasn't the point, was it? If the

poem had taught her anything --- and she could hear the

high-pitched hectoring whine of her twelfth-grade English teacher,

Mr. Parminter, rising up somewhere out of the depths of her

consciousness --- it was about nature, the power of it, the

hugeness. Don't press your luck. Don't upset the balance. Let the

albatross be. Let all the creatures be, for that matter . . .

except maybe the lobsters. She smiled in the dark at the

recollection of Mr. Parminter and that time that seemed like a

century ago, when poems and novels and theorems and equations were

the whole of her life. She could hardly believe it had only been

four years since she'd graduated.

Her bare feet swung out of the berth. The deck was solid, cool,

faintly damp. She was wearing a flannel nightgown that covered her

all the way to her toes, though she wished she'd been able to wear

something a little sheerer for Till's sake --- but that would have

to wait until they were back home in the privacy of their own

bedroom. She was modest and decent, not like the other girls who'd

gone out and cheated on their men overseas the first chance they

got, and she just didn't feel comfortable showing herself off in

such close quarters with Warren there, even if he was Till's

brother. She'd seen the way Warren looked at her sometimes, and it

was no different from what she'd had to endure since she'd begun to

develop in the eighth grade, leers and wolf whistles and all the

rest. She didn't blame him. He was a man. He couldn't help himself.

And she was proud of her figure, which was her best feature because

she'd never be what people would call pretty, or conventionally

pretty anyway --- she just didn't want to give him or anybody else

the wrong idea. She was a one-man woman and that was that. Unlike

Sandra, who looked as if she'd been around and who'd shown herself

off in a two-piece swimsuit when they'd run the boat down to San

Pedro the week before --- in a breeze that had her goosebumps all

over and wrapped in Warren's jacket by the time they got back to

the dock. But thank God for small mercies: Sandra had been unable

to join them this time around. She had an engagement in

North Hollywood, whatever that meant, but then that wasn't

Beverly's worry, it was Warren's.

She slipped into the head, used the toilet, drained her glass of

water and then drained another. Her stomach was queasy. That last

beer, that was what it was. She ran her fingers through her hair

and felt all the body gone out of it, though she'd washed and set

it just that morning. Or yesterday morning, technically. But she

was at sea now and she'd have to make do --- and so would Till, who

expected her to be made-up and primped and showing herself off like

one of the movie stars in the magazines. She cranked the hand pump

to flush, rinsed her hands --- precious water, precious --- eased

the door open and shut it behind her. As she slid back into bed she

was thinking she'd just have to tie her hair up in a kerchief, at

least till they got there and she could take a swim, depending on

how cold the water was, of course. Then she was thinking of the

mariner again and of Mr. Parminter, who wore a bow tie to class

every day and could recite "Ode on a Grecian Urn" by heart. Then

she was asleep.

When she woke again it was daylight and Till's berth was empty.

She tried to focus on the deck but the deck wouldn't stay put. A

great angry fist seemed to be slamming at the hull with a booming

repetitive shock that concussed the thin mattress and the plank

beneath it and worked its way through her till she could feel it in

the hollow of her chest, in her head, in her teeth. On top of it,

every last thing, every screw and bolt and scrap of metal up and

down the length of the boat, rattled and whined with a roused

insistent drone as if a hive of yellow jackets was trapped in the

hull. And what was that smell? Mold, hidden rot, the sour-milk reek

of her own unwashed body. Before she could think, she was leaning

over and spewing up everything inside her into the bucket she'd

kept at her bedside for emergencies --- the last of it, sharp and

acerbic as a dose of vinegar, coming on a long glutinous string of

saliva. She shook her head to clear it, wiped her mouth on the back

of her hand. Then she got up, fumbling for her blue jeans and a

sweater, Till's sweater, rough as burlap but the warmest thing she

could find and how had it gotten so cold?

It took her a while, just sitting there and picturing dry land,

a beach on the island, a rock offshore, anything that wasn't

moving, before she was able to get up and work her way into the

galley. She filled the percolator with water, poured coffee into

the strainer directly from the can without bothering to measure it

--- she could barely stand, let alone worry about the niceties, and

they'd want it strong in any case --- and then she set the pot on

the burner, but it kept tilting and sliding till she hit on the

idea of wedging it there with the big cast-iron pot she intended to

make chowder in when they got where they were going. If they ever

got there. And what had happened? Had the weather gone crazy all of

a sudden? Was it a typhoon? A hurricane?

She looked a fright, she knew it, and she'd have to do something

about her hair, but she worked her way up the juddering steps to

the bridge and flung herself down on the couch there --- or the

bench she'd converted to a couch by sewing ties to a set of old

plaid cushions she'd found in her parents' garage. The cabin was

close, breath-steamed, smelling of men's sweat and the muck at the

bottom of the sea. Till was right there, just across from her,

sitting in his chair at the controls, so near she could have

reached out and touched him. The wheel jumped and jumped again, and

he fought it with his left hand while forcing the throttle forward

and back in the clumsy stiff immalleable grip of the other one.

Warren leaned over him, grim-faced. Neither seemed to have noticed

her.

It was only then that she became aware of the height of the

waves coming at them, rearing black volcanoes of water that took

everything out from under the boat and put it right back again, all

the while blasting the windows as if there were a hundred fire

trucks out there with their hoses all turned on at once. And here

was the rhythm, up, down, up, and a rinse of the windows with every

repetition. "Where are we?" she heard herself ask.

Till never looked up. He was frozen there, nothing moving but

his arms and shoulders. "Don't know," Warren said, glancing over

his shoulder. "Halfway between Anacapa and Santa Cruz, but with the

way this shit's blowing, who could say?"

"What we need," Till said, his voice reduced and tentative, as

if he really didn't want to have to form his thoughts aloud, "is to

find a place to anchor somewhere out of this wind."

"That'd be Scorpion Bay, according to the charts, but that's"

--- there was a crash, as if the boat had hit a truck head-on, and

Warren, all hundred and eighty Marine-honed pounds of him, was

flung up against the window as if he was a bag full of nothing. He

braced himself, back pressed to the glass. Tried for a smile and

failed.

"That's somewhere out ahead of us, straight into the blow."

"How far?"

Warren shook his head, held tight to the rail that ran round the

bridge. "Could be two miles, could be five. I can't make out a

fucking thing, can you?"

"No. But at least we should be okay for depth. There's a lot of

water under us. A whole lot."

She looked out ahead of them to where the bow dipped to its

pounding, but she couldn't see anything but waves, one springing up

off the back of the other, infinite and impatient, coming and

coming and coming. Her stomach fell. She thought she might vomit

again, but there was nothing left to bring up. "What happened to

the weather?" she asked, raising her voice to be heard over the

wind, but it wasn't a question really, more an observation in

search of some kind of assurance. She wanted them to tell her that

this was nothing they couldn't handle, just a little blow that

would peter out before long, after which the sun would come back to

illuminate the world and all would be as calm and peaceful as it

was last night when the waves lapped the hull and the sandwiches

and beer went down and stayed down in the pure pleasure of the

moment. No one answered. She wasn't scared, not yet, because all

this was so new to her and because she trusted to Till --- Till

knew what he was doing. He always did. "I put on coffee," she said,

though the thought of it, of the smell and taste of it and the way

it clung viscously to the inside of the cup in a discolored slick,

made her feel weak all over again. "You boys" --- she had to force

the words out --- "think you might want a cup?"

Then she was back down in the galley, banging her elbows and

knees, flung from one position to another, and when she reached for

the coffeepot it jumped off the stove of its own volition and

scalded her right hand. Before she could register the shock of it,

the pot was on the deck, the top spun off and the steaming grounds

and six good cups of black coffee spewed across the galley. Her

first thought was for the deck --- the coffee would stain, eat

through the varnish like acid --- and before she looked to her burn

she was down on her hands and knees, caroming from one corner of

the cabin to the other like the silver ball in a pinball machine,

dabbing at the mess as she went by with a rag that became so

instantaneously and unforgivingly hot she burned her hand a second

time. When finally she'd got the deck cleaned up as best she could,

she fell back into the bench at the table, angry now, angry at the

boat and the sea and the men who'd dragged her out here into this

shitty little rattling sea-stinking jail cell, and she swore she'd

never go out again, never, no matter what promises they made.

"There'll be no coffee and I'm sorry, I am," she said aloud. "You

hear that?" she called out, directing her voice toward the steps at

the back of the cabin. "No coffee today, no breakfast, no nothing.

I'm through!"

The pain of the burn sparked then, assailing her suddenly with

an insidious throbbing and prickling, the blisters already forming

and bursting, and she thought of getting up and rubbing butter into

the reddened flesh on the back of her hand and between her scalded

fingers, but she couldn't move. She felt heavy all of a sudden,

heavier than the boat, heavier than the sea, so heavy she was

immovable. She would sit, that was what she would do. Sit right

there and ride it out.

That was when the water started coming in through the forward

hatch. That was when her feet got wet and she began to feel afraid.

That was when she thought for the first time of the life jackets

tucked in under the seats in the stern that was awash with the

piled-up waves --- and that was when she pulled herself along the

edge of the table to look up into the bridge and see her husband

and brother-in-law fighting over the controls even as she heard the

engines sputter and catch and finally give out. She caught her

breath. Something essential had gone absent in a way that was

wrong, deeply wrong, in violation of everything she'd known and

believed in since the moment they'd left shore. The ghost had gone

out of the machine.

In the sequel she was on the bridge, trying to make Till and

Warren understand about the water in the cabin, water that didn't

belong there, water that was coming in through a breach in the

forward hatch that was underwater itself before it shook free of

the weight of the waves and sank back down again. But Till wasn't

listening. Till, her rock, the man who'd survived the mangling of

his arm and the fiery blast of shrapnel that was lodged still in

his legs and secreted beneath the constellation of scars on the

broad firmament of his back, sat slumped over the controls,

distracted and drawn and punching desperately at the starter as

Warren, wrapped in a yellow slicker and cursing with every breath,

fought his way out the door to the stern while the wind sang

through the cabin and all the visible world lost its

substantiality.

Disbelieving, outraged, Till jerked at the controls, but the

controls wouldn't respond. The boat lolled, staggered, a wave

rising up out of nowhere to hit them broadside and drive down the

hull till she was sure they were going to capsize. She might have

screamed. Might have cried out uselessly, her breath coming hard

and fast. It was all she could do to hold on, her jaws clamped, the

spray taking flight up and over the cabin as Warren pried open the

hatch to the engine compartment, some sort of tool clutched in one

hand --- Warren, Warren out there on the deck to save the day, but

what could he hope to do? How could anybody fix anything in this

chaos?

He was a blotch of yellow in a world stripped of color, there

one moment and gone the next, a big breaching wave flinging him

back against the cabin door and pouring half an ocean into the

rictus of the engine well. Till snatched a look at her then, his

face drained and hopeless. Warren, the figure of Warren, flailing

limbs and gasping mouth, slammed at the window and rose impossibly

out of the foam, the slicker twisted back from his shoulders ---

inadequate, ridiculous, a child's jacket, a doll's --- and then he

was down again and awash. In the next instant Till sprang to his

feet, twisting up and away from the controls, the wheel swinging

wildly, lights blinking across the console, the scuppers inundated,

the bilge pump choking on its own infirmity. He took hold of her

wrist, jerking her up out of her seat, and suddenly they were

through the door and into the fury of the weather, the wind tearing

the breath out of her lungs, the next wave rearing up to knock her

to her knees with a fierce icy slap, and she wasn't sick anymore

and she wasn't tired or worn or dulled. Everything in her,

everything she was, howled at its highest pitch. They were going to

drown, all three of them, she could see that now. Drown and die and

wash up for the crabs.

"What do you think you're doing?" Warren, unsteady, hair painted

to his face, made to seize Till's arms as if he meant to dance with

him, even as Till shrugged him off and bent to release the

skiff.

"It's our only chance!" Till roared into the wind, his legs

tangled and rotating out of sync like a drunken man's. He flailed

at the shell of the skiff, jerked the lines in a fury.

"You're nuts!" Warren shouted. "Out of your fucking mind!" He

was staggering too, fighting for balance, and so was she, helpless,

the waves driving at her. The boat heaved, dead beneath their feet.

"We won't last five minutes in this sea!"

But here was the skiff, released and free and riding high, and

they were in it, Warren leaping to the oars, no thought of the life

jackets because the life jackets, for all their newness and

viability and their promise to keep men and women and children

afloat indefinitely even in the biggest seas, were tucked neatly

beneath that bench in the stern of the Beverly B. and the

Beverly B. was swamped. Stalled. Going down.

Heavily, like a waterlogged post in a swollen river, the boat

shifted away from them. They'd painted her hull white to contrast

with the natural wood of the cabin --- a cold pure unblemished

white, the white of sheets and carnations --- and that whiteness

shone now like the ghost image on a negative of a photograph that

would never be developed. Unimpeded, the waves crashed at the

windows of the cabin and then the glass was gone and the

Beverly B. shifted wearily and dropped down and came back

up again. The decks were below water now, only the cabin's top

showing pale against the dimness of the early morning and the spray

that rode the wind like a shroud.

Beverly was there to witness it, huddled wet and shivering in

the bow of the skiff, Till beside her, but she wasn't clinging to

him, not clinging at all because she was too rigid with the need to

get out of this, to get away, to get to land. No regrets. Let the

sea have the boat and all the time and money they'd lavished on

her, so long as it spared them, so long as the island was out there

in the gloom and it came to them in a rush of foam and black

bleeding rock. They rode up over two waves, three, and they were on

a wild ride now, wilder than anything the amusement park would ever

dare offer, and all at once they were in a deep pit lined with

walls of aquamarine glass, everything held suspended for a single

shimmering moment before the walls collapsed on them. She felt the

plunge, the force of it, and all of a sudden she was swimming free,

the chill riveting her, and it was instinct that drove her away

from the skiff and back to the Beverly B. for something to

hold fast to --- and there, there it was, rising up and plunging

down, and she with it. The wind tore at her eyes. The salt

blistered her throat.

She didn't see Warren, didn't see where he was, but then she'd

got turned around and he could be anywhere. And Till --- she

remembered him coming toward her, his good arm cutting the black

sheet of the water, until he wasn't coming anymore. Where was he?

The waves threw up ramparts and she couldn't see. He was calling

her, she was sure of it, in the thinnest distant echo of a cracked

and winnowed voice, Till's voice, sucked away on the wind until it

was gone. "Where are you?" she called. "Till? Till?"

The waves took her breath away. Her bones ached. Her teeth

wouldn't stop chattering. A period of time elapsed --- she couldn't

have said how long --- and nothing changed. She clung to the

heaving corpse of the Beverly B. because the Beverly

B. was the only thing there was. At some point, because they

were binding her feet, she ducked her head beneath the surface to

tear off her tennis sneakers and release them into the void. Then

she loosed her blue jeans, the cuffs as heavy as lead weights.

When finally the Beverly B. cocked herself up on a wave

as big as a continent and then sank down out of sight, she fought

away from the vortex it left in its wake and found herself treading

water. The waves lifted and released her, lifted and released her.

She was alone. Deserted. The ship gone, Till gone, Warren. She

could feel something flapping inside her like a set of wings, her

own panic, the panic that whipped her into a sudden slashing

breaststroke and as quickly subsided, and then she was treading

water again and she went on treading water for some portion of

eternity till there was nothing left in her arms. Till's sweater

dragged at her. It was too much, too heavy, and it gave her

nothing, not warmth, not comfort, not Till or the feel or smell of

him. She shrugged out of it, snatched a breath, and let it drift

down and away from her like the exoskeleton of a creature new-made,

born of water and salt and the penetrant chill.

She tried floating on her back but the wind drove the sea up her

nose and into her mouth so that she came up coughing and spewing.

Had she drifted off? Was she drowning? Giving up? She fought the

rising fear with her spent arms and the feeble wash of her spent

legs. After a time, she lost all feeling in her limbs and she went

down with a lungful of air and the air brought her back up, once,

twice, again. She thrashed for a handhold, for anything, for

substance, but there was no solid thing in all that transient

medium where the dolphins grinned and the flying fish flew and the

sharks came and went as they pleased.

And Till? Where was Till? He could have been right there, ten

feet away, and she wouldn't have known it. She closed her eyes,

snatched a breath, let herself drift down and let herself come back

again. Once more. Could she do it once more? She'd never known

despair, but it was in her now, colder than the water, creeping

numbly up from her feet and into her ankles and legs and torso,

overwhelming her, claiming her degree by degree. Water, water

every where. Just as she was about to surrender, to open

herself up, open wide and let the harsh insistent unforgiving

current flow through her and tug her down to where the waves

couldn't touch her ever again, the ocean gave her something back:

it was a chest, an ice chest, floating low in the water under the

weight of its burden. A silver thing, silver as the belly of her

fish. Sears & Roebuck. Guaranteed for life. She claimed it as

her own, and though she couldn't get atop it, it was there and it

sustained her as the wind bit and the sun rose up out of the gloom

to parch her lips and scorch the taut white mask of her upturned

face.

She had never been so thirsty in all her life. Had never known

what it was, what it truly meant, when she read in the magazines of

the Bedouin tumbling from their camels and their camels dying

beneath them or the G.I.'s stalking the rumor of Rommel's Panzers

across the dunes of North Africa and water only a mirage, because

she'd lived in a house with a tap in a place where the grass was

wet with dew in the morning and you could get a Coca-Cola at any

lunch counter or in the machine at the service station around the

corner. If she was thirsty, she drank. That was all.

Now she knew. Now she knew what it was like to go without, to

feel the talons clawing at your throat, the tongue furred and

bloating in the tomb of your mouth, barely able to swallow, to

breathe. There was ice in the chest --- and beer, chilled beer, the

bottles clinking and chirping with the rhythm of the waves --- but

she didn't dare crack the lid, even for an instant. It was the air

inside that kept her afloat and if she lifted the lid the air would

rush out and where would she be then? The bottles clinked. Her

throat swelled. The sun beat at her face. But this was a special

brand of torture, reserved just for her, worse than anything

devised by the most sadistic Jap commandant, and she kept wondering

what she'd done to deserve it --- the ice right there, the beer,

the sweet cold sparkling pale golden liquid in the bottle that

would shine with condensation just inches away, and she dying of

thirst.

She swallowed involuntarily at the thought of it, the lining of

her throat as raw as when she'd had tonsillitis as a girl and

twisted in agony with the blinds closed and the starched rigid

sheets biting into her till her mother came like an angel of mercy

with ginger ale in a tall cold glass, with sherbet, Jell-o, ice

cubes made of Welch's grape juice to suck and roll over her tongue

and clench between her teeth till all the moisture was gone. Her

mother's hand reached out to her, she saw it, saw it right there

framed against the waves, and her mother's face and the dripping

glass poised in her hand. It was too much to bear. She gave in and

wet her lips with seawater, though she knew she shouldn't, knew it

was wrong and would only make things worse, and yet she couldn't

help herself, her tongue probing and lapping as if it weren't

attached to her at all. The relief was instantaneous, flooding her

like a drug --- water, there was water inside her. But then, almost

immediately, her throat swelled shut and her cracked lips began to

bleed.

To bleed. That was the secondary problem: blood. Both

her elbows were scraped and raw and there was a deep irregular gash

on the back of her left hand, the one the scalding coffee hadn't

touched. How it had got there, she couldn't say, and she was so

numb from the cold she couldn't feel the sting of it, though

clearly it would need stitches to close the wound and there'd be a

scar, and for some time now she'd been idly examining the torn

flesh there, thinking she'd have to see a doctor when they got back

and already making up a little speech for him, how she'd want a

really top-notch man because she just couldn't stomach having her

skin spoiled, not at her age. But she was bleeding in the here and

now, each wave washing the gash anew and extracting from it a pale

tincture of pinkish liquid that dissolved instantly and was gone.

That liquid was blood. And blood attracted sharks.

Again the flap of panic. Her legs trailed behind her like lures,

like a provocation, like bait, and she couldn't see them, could

barely feel them. If the sharks came --- when they came --- she'd

have no defense. She was trapped in a childhood nightmare, a

vestigial dream of the time before there was land, when all the

creatures there were floated free amidst the flotilla of shining

jaws that would swallow them. She tried to hold her hand up out of

the water. Tried not to think about what was beneath her, behind

her, rising even now from the lazy depths like a balloon trailing

across the sky at dusk. But she had to think. Had to terrify

herself just to stay alive.

For as long as the ice chest had been there she'd maneuvered

around it, straddling it like an equestrian as it rode beneath the

clamp of her thighs, pushing it all the way down to tamp it with

her feet and perch tentatively atop the tenuous wavering shelf of

it, lying flat with its lid tucked between her abdomen and breasts

so that her back was arched and her legs could spread wide for

balance. Now she tried to huddle atop it, to kneel beneath the full

weight of her limbs and torso as if she were praying --- and she

was praying, she was --- struggling to hold her gashed hand clear

of the water and balance there like an acrobat stalled on the high

wire, but the waves wouldn't allow it. She kept slipping down while

the cooler bobbed up and away from her so that she had to swim free

and snatch it back in a single searing beat of white-hot terror,

thinking only of a mute streaking shape lunging out of the depths

to snatch her up in its basket of teeth.

She'd seen a shark only once in her life. It was on the Santa

Monica pier, just after Till had come home from overseas. They'd

walked on the beach for hours and then promenaded all the way to

the end of the pier, her arm in his, the stripped pale boards

rocking gently beneath their feet and the sea air deliciously cool

against their skin. She was so alive in that moment, so attuned to

Till and his transformation from the recollected to the actual, to

the flesh, to the hand round her waist and the voice murmuring in

her ear, that the smallest things thrilled her with their novelty,

as if no one had ever conceived of them before. A paper cone of

cotton candy, so intensely pink it was otherworldly, seemed as

strange to her as if it had been delivered there by Martians from

outer space. Ditto the tattooed man exhibiting himself in his

bathing trunks in the hope of spare change and the eighty-year-old

beauty queen in the two-piece --- even the taste of the burger with

chopped raw onions and plenty of catsup they ate standing under the

sunstruck awning of the stand at the foot of the pier that was like

no other burger she'd ever had. Her feet weren't even on the

ground. They were there in the flesh, both of them, she and Till,

strolling along like any normal couple who could go home to bed

anytime the urge took them, day or night, or go get a highball and

listen to the jukebox in the corner of some dark roadhouse or drive

slow and sweet along Ocean Boulevard with the windows down and the

breeze fanning their hair. It was her dream made concrete. But

then, right there in the middle of that dream, was the shark.

There was a crowd gathered at the far end of the pier and they'd

gone toward it casually, out of idle curiosity, people looping this

way and that, little kids squirming through to the front for a

closer view, and there it was, more novelty, the first shark she'd

ever seen outside of a picture book. It was suspended by its tail

on a thick braid of cable that held it, dripping, just above the

bleached boards of the dock. The fisherman --- a Negro, and that

was a novelty too, a Negro fisherman on the Santa Monica pier ---

stood just off to the left of it while his companion, another

Negro, took his photograph with a Brownie camera. "Hold steady

now," the second man said. "Less have a smile. C'mon, give us a

grin."

A woman beside her made a noise in her throat, an admixture of

disgust and fascination. "What is it?" the woman said. "A

swordfish?"

The first man, the fisherman, smiled wide and the camera

clicked. "You see a sword?" he asked rhetorically. "I don't see no

sword."

"It's a dolphin," somebody said.

"Ain't no dolphin," the fisherman retorted, enjoying himself

immensely. "Ain't no tunafish neither." He bent close to the thing,

to the half-moon of the gill slit and the staring eye, and then

cupped a hand over the unresisting snout and tugged upward. "See

them teeth?"

And there they were, suddenly revealed, a whole landscape of

stacked and serrated teeth running off into the terra incognita of

the dark gullet, and it came to her that this was a shark, the

scourge of the sea, the one thing that preyed on all the rest, that

rose up in a blanket of foam to ravage a seal or maim a surfer and

ignite an inflammatory headline out of La Jolla or Redondo Beach

that everybody forgot about a week later.

"What this is, what you looking at right now? This a great white

shark, seven feet six inches long. As bad as it gets. And this

one's not much more than a baby. Hell, they five feet long when

they come out their mother."

The crowd pressed in. Till's eyes were gleaming, and this was a

thing he could appreciate, a man's thing, as bad as it

gets. There was only one question left to ask and she heard

her own voice quaver as she asked it: "Where did you catch it?"

A pause. A smile. Another click of the camera. "Why, right here,

right off the end of the dock."

The image had stayed with her a long while. She'd asked Till

about it, about how that could be, what the man had said --- right

off the dock, right there where she'd been swimming since she was a

little girl --- and he'd tried to reassure her. "They can turn up

anywhere, I suppose," he said, "but it's rare here. Really rare."

He gave her a squeeze, pulled her to him. "Where you really find

them," and he pointed now, out into the band of mist that fell

across the horizon, "is out there. Off the islands."

People died of shark bite. They died of thirst. Of hypothermia.

She was dressed in nothing but bra and panties, naked to the water

and the water sucking the heat from her minute by minute, and she

clung there and shivered and felt the volition go out of her. Let

the sharks come, she was thinking, dreaming, the cold lulling her

now till she was like the man in that other Jack London story, the

one who laid himself down and died because he couldn't build a

fire. Well, she couldn't build a fire either because water wouldn't

burn and there was nothing in this world that wasn't water.

She woke sputtering, choked awake, a cold fist in her throat.

She was coughing --- hacking, heaving, retching --- and the

violence of it brought her back again. Sun, sea, wind, waves. Sun.

Sea. Wind. Waves. The ice chest bobbed and she bobbed with it. And

then, all at once, there was something else there with her,

something new, a living thing that broke the surface in a fierce

boiling suddenness that annihilated her, the shark, the shark come

finally to draw the shroud. She shut her eyes, averted her face.

She didn't draw up her legs because there was no point in it now,

the drop was coming, the first rending shock of the jaws, sadness

spreading though her like a stain in water, sadness for Till, for

her parents, for what might have been . . . but the next moment

slipped by and the moment after that and still she was there and

still she was whole, bobbing along with the ice chest, bobbing.

The next splash was closer. She forced open her eyes, tried to

focus through the drooping curtains of her swollen lids. Her pupils

burned. The blood pounded in her ears. It took her a moment to

understand that this wasn't a shark, wasn't a fish at all --- fish

didn't have dog faces and whiskers and eyes as round and darkly

glowing as a human's. She stared into those eyes, amazed, until

they sank away in the wash and she looked beyond the swirl of foam

to the sun-scoured wall of rock rising out of the mist above

her.

Anacapa is the smallest of the four islands that form the

archipelago of the northern channel islands and the closest to the

mainland, a mere eleven miles from its eastern tip to the harbor at

Oxnard. It parallels the coast in its east/west orientation, from

Arch Rock in the east to Rat Point on the western verge, and is,

geologically speaking, a seaward extension of the Santa Monica

Mountains. In actuality, Anacapa comprises three separate islets,

connected only during extreme low tides, and it is of volcanic

origin, composed primarily of basalt dating from the Miocene

period. All three islets are largely inaccessible from the sea,

featuring tall looming circumvallate cliffs and strips of

cliff-side beach that darkly glisten with the detritus ground out

of the rock by the action of the waves. As seen from the air, the

islets form a narrow snaking band like the spine of a sea serpent,

the ridges articulated like vertebrae, claws fully extended, jaws

agape, tail thrashing out against the grip of the current. Seabirds

nest atop the cliffs here and on the tableland beyond --- Xantus'

murrelet, the brown pelican and Brandt's cormorant among them ---

and pinnipeds racket along the shore. Average rainfall is less than

twelve inches annually. There is no permanent source of water.

Beverly knew none of this. She didn't know that the landfall

looming over her was Anacapa or that she'd drifted some six miles

by this point. She knew only that rock was solid and water was not

and she made for it with all the strength left in her. Twice she

went under and came up gasping and it was all she could do to keep

hold of the ice chest in the roiling surf that had begun to crash

round her. All at once she was in the breakers and the chest was

torn from her, gone suddenly, and she had no choice but to squeeze

her eyes shut and extend her arms and ride the wave till the force

of it flung her like so much wrack at the base of the cliff. Stones

rolled and collided beneath her knees and the frantic grabbing of

her hands, she was tossed sideways and the breath pounded out of

her, but her fingers snatched at something else there, sand, the

floor of a beach gouged out of the rock. It was nothing more than a

semicircular pit, churning like a washing machine, but it was

palpable and it held her and when the wave sucked back she was

standing on solid ground. She might have felt a surge of relief,

but she didn't have a chance. Because she was shivering. Dripping.

Staggering. And the next wave was already coming at her.

The foam shot in, sudsing at her knees, driving her back

awkwardly against the punishing black wall of the overhang. She

found herself stumbling to her left, even as the next breaker

thundered in, and then she was crawling on hands and knees up and

away from it, the rock pitted and sharp and yet slick all the same,

up and out of the water and onto a narrow perch that was no wider

than her berth on the Beverly B. She hugged her knees to

her chest, clamped her hands round her shoulders, shaking with

cold. Her hair hung limp in her face. The waves crashed and

dissolved in mist and everything smelled of funk and rot and the

protoplasmic surfeit of all those galaxies of wheeling, biting,

wanting things that hadn't survived the day. She didn't think about

Till or the boat or Warren, her mind drawn down to nothing. She

just stared numbly at the wash as it stripped the beach and gave it

back again, torn strands of kelp struggling to and fro, a float of

driftwood, the suck and roar, and then she was asleep.

When she woke it was to the sun and the beach that had grown

marginally bigger, a scallop of blackly glistening sand emerging

from the receding tide, the teeth of the rocks exposed now and the

wet gums clamped beneath them. She'd been in the shadows all this

time, huddled on her perch, tucked away from the tidal wash and the

sun too, but now the sun had moved out into the channel and the

heat of it touched her and roused her. For a long while she sat

there, absorbing the warmth, and if she was sunburned it didn't

matter a whit because she'd rather be burned than frozen, burned

anytime, scorched and roasted till she peeled, because anything was

better than the cold locked up inside her, a numbness so deeply

immured in her she might as well have been a corpse. She gazed out

on the sea with a kind of hatred she'd never known, hating the

monotony of it, the indifference, the marrow-draining chill. And

then, abruptly, she was thirsty. Still thirsty. Thirstier than

she'd been out there on the sea when she was thirstier than she'd

ever been in her life.

In that moment her eye jumped to the gleam of metal at the near

end of the cove. The ice chest. There it was, upright in the sand,

its lid still fastened. She sprang down from the rock, slimed and

filthy, her limbs battered and her tongue made of felt, and ran to

it, tore back the lid and saw that the ice was gone and the bottles

smashed --- all but one, the precious last remaining dark brown

sweating bottle with the label soaked off and sand worked up under

the cap. Lifting the beer to the sun, she could see that it was

intact, its bubbles infused with light and rising in a slow

hypnotic dance. Beer. Cold beer. But she had no opener, no

churchkey, no knife or screwdriver or tool of any kind. And where

was Till? Where was he when she needed him?

She remembered how casually he would slam the neck of his beer

against the edge of the counter or the work bench in the garage and

how instantly the cap would fly up and away and the cold aperture

of the bottle came to his lips, all in a single fluid motion, as if

the opening and the draining of the bottle comprised the same

continuous physical process. Overhead, chased on a draft, a gull

appraised her, mewed over her torn and abraded flesh, and was gone.

She looked wildly around her for something, anything, to make a

tool of, but there was nothing but sand and driftwood and rock.

Rock. Rock would do it. Of course it would. And then

she was smoothing her hand over the wall of the overhang, feeling

for a rough spot, a ledge, any kind of projection, and here, here

it was, the cap poised just so and the weight of her burned hand

coming down on it, once, twice . . . and nothing. She worked at it,

frantic now, angry, furious, but the best she could do was flatten

the ridges till the cap was even more secure than when she'd begun,

and it was too much, she couldn't take a single second more of this

--- and then it was done, the neck shattered and gaping and she

draining the whole thing in three airless gulps and if there was

glass in it and if the glass cut her open from esophagus to gut she

didn't give a damn because she was drinking and that was the only

thing that mattered.

But the beer was gone and the thirst was there still, rattling

inside her like a field of cane in a desert wind, and was it any

surprise she was light-headed? She'd always been a capable drinker,

proud of her ability to match Till beer for beer, but this one hit

her hard and before she knew it she was down in the sand, sitting

there cross-legged like a statue of the Buddha, as if that was what

she'd meant to do all along. The sun seemed to have shifted somehow

in the interval, dropping down close to the flattening gray surface

of the sea where the fog could take hold of it and snuff it out

like the burned-up butt of the cigarette she suddenly wanted as

much as she wanted water. She stood shakily and went to the ice

chest. It was right where she'd left it not ten minutes ago (or had

it been longer? Had she dozed off?), but now the incoming tide was

running up the beach to take it from her all over again. Seizing it

by one corner, she dragged it awkwardly across the sand to the

declivity beneath the overhang, then worked it up to her perch six

feet above the beach. Inside, amidst the litter of broken bottles

and stripes of sand and weed, there was a liquid that might have

been a mix of beer and meltwater, that might have been potable,

that might have quenched her thirst, but when she thrust a finger

into it and licked that finger all she could taste was salt.

Dusk fell, aided and abetted by the fog, which closed off the

beach even as the tide ran in, and though the water was up past her

knees, she probed the scalloped ledges at both ends of the cove,

looking for a way out. She braced herself, one foot up, then the

other, straining for a handhold. Working patiently, her face

pressed to the rock, she got as high as fifteen or twenty feet

above the beach, but after she fell for the third time, coming down

hard amidst the litter and the cold shock of the water, she gave

up. It was no use. She was trapped. A single pulse of panic

flickered through her, but she suppressed it. She wasn't afraid,

not anymore --- that was behind her. All she felt was frustration.

Anger. Why had she been spared only to wash up here to die of

thirst, hunger, cold? Where was God's hand in that? Where was His

purpose? Finally, when it was fully dark and the fog settled in so

impenetrably as to close off even the stars, let alone the running

lights of any boat that might have been plying the channel looking

for them, for survivors --- and here she saw Till and Warren,

wrapped in blankets in a gently rocking cabin, the glow of the

varnished wood, lanterns a-sway, mugs of hot coffee pressed to

their lips --- she held fast to the ice chest and willed herself

asleep.

In the morning, at first light, there was the sound of the gulls

that was like the opening and closing of a door on recalcitrant

hinges, but there was no door here, no bed or room or clothes or

warmth, and she couldn't see the gulls for the fog. She shivered

into the light, slapping at her thighs and shoulders and huddling

in the cradle of her arms, and then the thirst took hold of her. It

roused her and she rose to her feet, fighting for balance, the tide

having receded and risen all over again, reducing her world to this

rock and the wall above her. She wanted a pitcher of water, that

was all, envisioning the white bone china pitcher in the kitchen at

home, a hand-me-down from her mother she brought out for special

occasions, and it took her a long moment to realize that there was

a persistent cold drip tapping at her shoulder and that she'd been

shifting unconsciously to avoid it. She lifted her face and saw

that the cliff was wet, the fog whispering across the rock above

her, condensing there, dripping, dripping.

What she didn't know was that forty years earlier a man named H.

Bay Webster had leased the island from the federal government for

the purpose of raising sheep, but that the sheep had failed to

thrive because of overgrazing and lack of water, and that finally,

in their distress, had been reduced to licking the dew each from

the other's fleece in order to survive. Not that it mattered. All

that mattered was this drip. She held her tongue out to it, licked

the rock as if it were a snow-cone presented to her by the lady

behind the concession stand at the county fair. And when one of the

little green shore crabs came within reach, a flattened thing, no

more than two inches across, she crushed it beneath her foot and

then fed the salty cold wet fragments into her mouth.

It took her a long while after that to get her courage up,

because she knew now what she had to do though her whole being

revolted against it. She kept praying that someone would come for

her, that the prow of a ship would ease out of the fog or a rope

come hurtling down from above, anything to spare her getting back

into that killing water. The funny thing was that she'd always

liked swimming --- she'd joined the swim team in school and trained

so relentlessly her hair never seemed to be really dry her whole

senior year --- but now, as she climbed down from the rock,

clutched the ice chest to her and fought through the surf, she

hated it more than anything in the world. Instantly, she was cold

through to the bone and thrashing for warmth, then she was fighting

past the breakers and out into the sea.

Here was the nightmare all over again, but this time there was a

difference because she was saved, she'd saved herself, and she kept

close to shore, trembling, yes, exhausted, thirsty, but no longer

panicked. There wouldn't be sharks, not this close in, not with the

sea full of seals, armies of them barking from the rocks and

sending up a sulfurous odor of urine and feces and seal stink. The

sea was calmer now too, much calmer --- almost gentle --- and from

time to time she tried floating on her back, head propped on the

chest and elbows jackknifed behind her, but invariably she had to

roll over and pull herself up as far as she could in an effort to

escape the cold. Fog clung to her. Great fields of kelp, dun stalks

and yellowed leaves, drifted past. Tiny fishes needled the water

around her and were gone.

As the morning wore on, the world began to enlarge above her,

birds uncountable lifting off into the fog and gliding back again

like ghosts in the ether, the cliffs decapitated above skirts of

guano, shrubs and even flowers so high up they might have been

planted in air. She let the current carry her, periodically forcing

herself to unfurl her legs and paddle to keep on course, telling

herself that at any moment she'd come upon a boat at anchor or a

beach that spread back to a canyon where she could get up and away

from the sea. How far she'd drifted or how long she'd been in the

water, she had no way of knowing, the cold sapping her, lulling

her, killing her will, every seal-strewn rock and every black-faced

cliff so exactly like the last one she began to think she'd circled

the island twice already. But she held on, just as she had when the

Beverly B. went down a whole day and night ago, because it

was the only thing she could do.

It must have been late in the morning, the sun lost somewhere in

the fog overhead, when finally she found what she was looking for.

Or, rather, she didn't know what she was looking for until it

materialized out of the haze in a cove that was no different from

all the rest. A rust-peached ladder, so oxidized it was the color

of the starfish clinging to the rocks beneath it, seemed to glide

across the surface to her, and when she took hold of it she let the

chest float free, pulling herself from the water, rung by rung, as

from a gently yielding sheath.

The universe stopped rocking. The sea fell away. And she found

herself on a path leading steeply upward to where the fog began to

tatter and bleed off till it wasn't there at all. Above her,

opening to the sun and the chaparral flecked with yellow blooms

that climbed beard-like up the slope, was a shack, two shacks,

three, four, all lined up across the bluff as if they'd grown out

of the rock itself. The near one --- flat-roofed, the boards

weathered gray --- caught the flame of the sun in its windows till

it glowed like a cathedral. And right beside it, where the

drainpipe fell away from the roof, was a wooden barrel, a hogshead,

set there to catch the rain.

She was in that moment reduced to an animal, nothing more, and

her focus was an animal's focus, her mind stripped of everything

but that barrel and its contents, and she never felt the fragmented

stone of the path digging into her feet or the weight of the sun

crushing her shoulders, never thought of who might be watching her

in her nakedness or what that might mean, till she reached it and

plunged her face into its depths and drank till she could feel the

cool silk thread coming back up again. It was only then that she

looked around her. Everything was still, hot, though she shivered

in the heat, and her first thought was to call out, absurdly, call

"Hello? Is anybody there?" Or why not "Yoo-hoo?" Yoo-hoo would have

been equally ridiculous, anything would have. She was as naked as

Eve, her blue jeans gone, Till's sweater jettisoned, her

underthings torn from her at some indefinite point in the shifting

momentum of her battle against the current and the waves and the

sucking rasp of the shingle. When she touched herself, when she

brought her hands up to cover her nakedness, they were like two

dead things, two fish laid out on a slab, and she fell to her knees

in the dirt, hunched and shivering and looking round her with an

animal's dull calculation.

In the next moment she rose and went round the corner of the

house to the door at the front, thinking to clothe herself,

thinking there must be something inside to cover up with, rags, a

bedsheet, an old towel or fisherman's sweater. But what if there

were people in there? What if there was a man? No man on this earth

had seen her naked but for the doctor who'd delivered her and Till,

and what would she say to Till if there was a man there to see her

as she was now? She hesitated, uncertain of what to do. For a long

moment she regarded the door in its stubborn inanimacy, a door made

of planks nailed to a crosspiece, weather-scored and unrevealing.

Beside it, set in the wall at eye-level, was a four-pane window so

smeared as to be nearly opaque, but she shifted away from the door,

cupped her hands to the glass and peered in, all the while feeling

as if she were being watched.

Inside, she could make out a crude kitchen counter with a

dishpan and an array of what looked to be empty bottles scattered

atop it, and beyond that, a sagging cot decorated with an army

blanket. A second window, facing north, drew the glare in off the

ocean. She tapped at the glass, hoping to forestall anyone who

might be lurking inside. Finally, she tried the door, whispering

"Hello? Is anybody home?"

There was no answer. She lifted the latch and pushed open the

door to a rustle of movement, dark shapes inhabiting the corners, a

spine-sprung book on the floor, shelves, cans, a sou'wester on a

hook that made her catch her breath, fooled into thinking someone

had been standing there all along. It took a moment for her eyes to

adjust, the shapes manifesting themselves all at once --- furred,

quick-footed, tails naked and indolently switching, a host of

darkly shining eyes fastening on her without alarm or haste because

she was the interloper here, the beggar, she was the one naked and

washed up like so much trash --- and she let out a low exclamation.

Rats. She'd always hated rats, from the time she was in

Kindergarten and her mother warned her against going near the

garbage cans set out in the alley behind their apartment building

--- "They bite babies," her mother told her, "big girls too, nip

their toes, jump in their hair. You know Janey, upstairs in 7B?

They got in her cradle when she was baby. Right here, right in this

building." Her father reinforced the admonition, taking her by the

hand and probing with one shoe in the dim corners of the carport so

she could see the animals themselves, the corpses of the ones he'd

caught in spring traps baited with gobs of peanut butter. In

secret, in the dark, they would lick and paw that bait --- peanut

butter, the same peanut butter she ate on white bread with the

crusts cut off --- until the guillotine dropped and the blood

trailed from their crushed heads and dislocated jaws.

Rats. Disease carriers, food spoilers, baby biters. But

what were they doing here on an untamed island set out in the

middle of the sea? Had they swum? Sprouted wings?

The thought came and went. She flapped her arms savagely. "Get

out!" she shouted, rushing at them, whirling, clapping her hands.

"Get!" They blinked at her --- there must have been a dozen or more

of them --- and then, very slowly, as if it were an imposition, as

if they were obeying only because in that moment her need was

stronger than theirs, they crept back into their holes. But she was

frantic now, snatching the blanket up off the cot without a thought

for the rattling dried feces that fell like shot to the floor and

wrapping it around her even as she fumbled through the cans on the

shelf --- peaches in syrup, Boston baked beans, creamed corn ---

and the utensils tossed helter-skelter in a chipped enamel dishpan

set on the counter.

She ate standing. First the peaches, the soothing thick syrup

better than anything she'd ever tasted --- syrup to lick from the

spoon and then from her fingertips, one after the other --- then

the creamed corn, spooned up out of the can in its essential

sweetness, and then, finally, a can of tuna for the feel of it

between her teeth. Only when she was sated did she take the time to

look around her. The empty cans, evidence of her crime --- theft,

breaking and entering --- lay at her feet. She sank down on the

cot, pulling the rough blanket tight round her throat, and saw,

with a kind of restrained interest, that the walls were papered

over with full sheets torn from magazines, from Life and

Look and the Sunday rotogravure. Pinups gazed back at her,

men perched on tanks, Barbara Stanwyck astride a horse. A man lived

here, she decided, a man lived here alone. A hermit. A fisherman.

Someone shy of women, with whiskers like in the old photos of her

grandfather's time.

She found his clothes in the trunk in the corner. Two white

shirts, size small, a blue woolen sweater with red piping and a

stained and patched pair of gabardine trousers. Without thinking

twice --- she'd pay him back ten times over when they came to

rescue her --- she slipped into the trousers and the less homely of

the two shirts and then stepped back outside to see if she could

find him. Or one of the men who must have lived in the other

shacks, because if there were four shacks there must have been four

men. At least. And now, standing outside the door with her face

turned to the nearest shack, some hundred feet away, she did, in

fact, call out "Yoo-hoo!"

No one answered. The only sounds were the ones she'd become

inured to: the sifting of the wind, the slap and roll of the

breakers, the strained high-flown cries of the birds. She went to

each of the shacks in succession, and though she found signs of

recent habitation --- a bin of rat-gnawed potatoes, a candle melted

into a saucer, more canned goods, crackers gone stale in a tin,

fishing gear, lobster traps, two jugs of red wine and what might

once have been sherry turning black in the unmarked bottle beneath

a float of scum --- she didn't find anyone at home. It was as if

she were one of the wandering orphans of a fairy tale arrived in

some magical realm where all the inhabitants had been put under a

spell, turned to trees or animals --- to rats, black rats with no