Excerpt

Excerpt

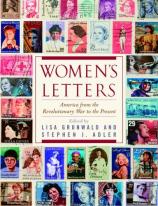

Women's Letters: America From the Revolutionary War to the Present

REVOLUTION

1775-1799

I hear by Captn Wm Riley news that makes me very Sorry for he Says you proved a Grand Coward when the fight was at Bunkers hill. . . . If you are afraid pray own the truth & come home & take care of our Children & I will be Glad to Come & take your place, & never will be Called a Coward, neither will I throw away one Cartridge but exert myself bravely in so good a Cause.

--- Abigail Grant to her husband

August 19, 1776

BETWEEN 1775 AND 1799 . . . 1775: Patrick Henry attempts to persuade Virginia to arm its militia against the British, declaring: "I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty or give me death." The first shots of the Revolutionary War are fired at Lexington and Concord. In Salem, following the first news of the war, 13-year-old Susan Mason Smith chooses not to remove her shoes for several days, wanting to be prepared in case her family decides to flee. Only about half the white women in the colonies are literate enough to sign their names. 1776: With her husband, John, away at the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, Abigail Adams writes to him frequently and urges him to make sure that he and his colleagues "Remember the Ladies" while they are shaping the new nation; if they don't, she warns him, "we are determined to foment a Rebelion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation." Thomas Paine publishes Common Sense, a 50-page pamphlet that urges Americans to fight not only against taxation but also for independence; it sells more than half a million copies within its first few months. Betsy Ross (according to the legend that's been neither proven nor refuted by evidence) is visited by George Washington and asked to make a national flag; the stars on her design will have five points, rather than the six Washington suggests. In his first draft of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson writes: "We hold these truths to be sacred & undeniable; that all men are created equal & independant, that from that equal creation they derive rights inherent & inalienable, among which are the preservation of life, & liberty, & the pursuit of happiness." For 67 days, the new country is called "The United Colonies of America"; in September, Congress gives the USA its official name. 1777: Sybil Ludington, the 16-year-old daughter of a New York militia officer, rides almost 40 miles to muster troops against the British. More than 100 women gather at the Boston store of Thomas Boylston to protest the merchant's high wartime prices. General George Washington leads 11,000 militiamen to Valley Forge near British-occupied Philadelphia, where they are forced to spend a bitterly cold winter, plagued by widespread dysentery and typhus and a severe lack of food, clothes, and basic supplies. Washington writes in a letter that the soldiers' "marches might be tracked by the blood from their feet." 1778: During the Battle of Monmouth Court House in New Jersey, Mary McCauly earns the name "Molly Pitcher" after making frequent trips with water to cool down both the men and the cannon in her husband's regiment. 1781: Los Angeles is founded by Spanish settlers; its full name is El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Angeles de Porciuncula. 1783: The British evacuate New York. The Paris Peace Treaty ends the Revolutionary War. New Jersey, alone among the 13 states, enacts a statute giving women the vote; it will be put into sporadic use starting in 1787 --- and overturned in 1807. 1784: Abel Buell engraves and publishes the first map of the United States, "layd down from the latest observations and best authority agreeable to the peace of 1783." Judith Sergeant Murray publishes her essay "Desultory Thoughts upon the Utility of Encouraging a Degree of Self-Complacency, Especially in Female Bosoms," arguing that in the absence of sufficient confidence, women all too often marry precipitously to avoid the epithet spinster. 1786: In his sermon "On Dress," John Wesley declares: "slovenliness is no part of religion. . . . 'Cleanliness is, indeed, next to godliness,' " but warns: "The wearing [of] gay or costly apparel naturally tends to breed and to increase vanity. . . . You know in your hearts, it is with a view to be admired that you thus adorn yourselves, and that you would not be at the pains were none to see you but God and his holy angels." 1787: Despite Congress's plan merely to revise the 1777 Articles of Confederation, delegates draft a new constitution that gives increased power to a central government. 1788: Nine states ratify the Constitution, and it goes into effect. 1789: Though rich in land, George Washington must borrow £600 in cash to travel from Mount Vernon to New York City for his inauguration. 1790: The total population of the United States is 3,893,874, of whom 694,207 are slaves. Among white males, 791,901 are under the age of 16; 807,312 are 16 and over. 1791: Vermont becomes the fourteenth state. The national debt is $75,463,000, or roughly $18 a person. The Bill of Rights is ratified. 1792: George Washington signs an act providing for the creation of copper pennies and stipulating that "no copper coins or pieces whatsoever except the said cents and half-cents, shall pass current as money." The Old Farmer's Almanac debuts, offering weather predictions, tide tables, and occasional advice; it costs sixpence and has a first-year circulation of 3,000 that will triple in a year and after two centuries pass four million. 1794: Eli Whitney is granted a patent for the cotton gin, which combs and deseeds cotton 10 times faster than the nonmechanical process. 1796: Amelia Simmons publishes the first American cookbook under the title American Cookery, or the Art of Dressing Viands, Fish, Poultry and Vegetables, and the Best Modes of Making Puff-Pastries, Pies, Tarts, Puddings, Custards and Preserves, and All Kinds of Cakes, from the Imperial Plum to Plain Cake --- Adapted to This Country and All Grades of Life. 1798: More than 2,000 people die in a yellow fever epidemic in New York City. 1799: A Philadelphia Quaker named Elizabeth Drinker writes in her journal about the nearly novel experience of taking a bath: "I bore it better than I expected, not having been wett all over att once, for 28 years past."

1775: Circa April 18

Rachel Revere to Paul Revere

On April 18, 1775, Paul Revere (1735-1818) made his famous midnight ride to Lexington, Massachusetts, warning his countrymen of the British troops' planned attack. Revere was captured later that night, but his actions marshaled colonial troops to the famous first battle on Lexington Green, where the American Revolution began the next day. Once released, Revere started back toward Boston, despite having neither money nor horse. With this note, his worried wife, Rachel Walker Revere (1745-1813), tried to send him help. Dr. Benjamin Church was trusted by Rachel as a fellow rebel but was in fact a British spy. Rachel's letter was promptly turned over to the British.

My dear by Doctr Church I send a hundred & twenty five pounds and beg you will take the best care of your self and not attempt coming in to this town again and if I have an opportunity of coming or sending out any thing or any of the Children I shall do it pray keep up your spirits and trust your self and us in the hands of a good God who will take care of us tis all my dependance for vain is the help of man aduie my

Love from your

affectionate R Revere

1775: April 22

Anne Hulton to Elizabeth Lightbody

Anne Hulton (?-1779) was a sister of Boston's commissioner of customs and, like some 15 to 35 percent of the white colonial population, a British Loyalist. In this letter to her friend Elizabeth Lightbody, in Liverpool, she described the beginning of the war as it would come to be seen on the other side of the Atlantic, right down to the outrage of having His Majesty's troops attacked from behind trees and fences. By the end of the year, having endured months in a besieged city, Hulton would sail for England.

Inst was a common abbreviation for instant, meaning "the month this was written." The Grenadiers were elite British troops who wore long red coats and tall bearskin hats. A magazine, in this context, was a warehouse. Hugh Percy was a British brigadier general. The Otter was a British sloop that would engage in battle in the first week of May.

I acknowledged the receipt of My Dear Friends kind favor of the 20th Septr the begin'ing of last Month, tho' did not fully Answer it, purposing as I intimated to write again soon, be assured as your favors are always very acceptable, so nothing you say, passes unnoticed, or appears unimportant to me. but at present my mind is too much agitated to attend to any subject but one, and it is that which you will be most desirous to hear particulars of, I doubt not in regard to your friends here, as to our Situation, as well as the Publick events. I will give you the best account I can, which you may rely on for truth.

On the 18th instt at 11 at Night, about 800 Grenadiers & light Infantry were ferry'd across the Bay to Cambridge, from whence they marchd to Concord, about 20 Miles. The Congress had been lately assembled at that place, & it was imagined that the General had intelligence of a Magazine being formed there & that they were going to destroy it.

The People in the Country (who are all furnished with Arms & have what they call Minute Companys in every Town ready to march on any alarm), had a signal it's supposed by a light from one of the Steeples in Town, Upon the Troops embarkg. The alarm spread thro' the Country, so that before daybreak the people in general were in Arms & on their March to Concord. About Daybreak a number of the People appeard before the Troops near Lexington. They were called to, to disperse. when they fired on the Troops & ran off, Upon which the Light Infantry pursued them & brought down about fifteen of them. The Troops went on to Concord & executed the business they were sent on, & on their return found two or three of their people Lying in the Agonies of Death, scalp'd & their Noses & ears cut off & Eyes bored out --- Which exasperated the Soldiers exceedingly --- a prodigious number of the People now occupying the Hills, woods, & Stone Walls along the road. The Light Troops drove some parties from the hills, but all the road being inclosed with Stone Walls Served as a cover to the Rebels, from whence they fired on the Troops still running off whenever they had fired, but still supplied by fresh Numbers who came from many parts of the Country. In this manner were the Troops harrased in thier return for Seven on eight Miles, they were almost exhausted & had expended near the whole of their Ammunition when to their great joy they were releived by a Brigade of Troops under the command of Lord Percy with two pieces of Artillery. The Troops now combated with fresh Ardour, & marched in their return with undaunted countenances, recieving Sheets of fire all the way for many Miles, yet having no visible Enemy to combat with, for they never woud face 'em in an open field, but always skulked & fired from behind Walls, & trees, & out of Windows of Houses, but this cost them dear for the Soldiers enterd those dwellings, & put all the Men to death. Lord Percy has gained great honor by his conduct thro' this day of severe Servise, he was exposed to the hottest of the fire & animated the Troops with great coolness & spirit. Several officers are wounded & about 100 Soldiers. The killed amount to near 50, as to the Enemy we can have no exact acct but it is said there was about ten times the Number of them engaged, & that near 1000 of 'em have fallen

The Troops returned to Charlestown about Sunset after having some of 'em marched near fifty miles, & being engaged from Daybreak in Action, without respite, or refreshment, & about ten in the Evening they were brought back to Boston. The next day the Country pourd down its Thousands, and at this time from the entrance of Boston Neck at Roxbury round by Cambridge to Charlestown is surrounded by at least 20,000 Men, who are raising batteries on three or four different Hills. We are now cut off from all communication with the Country & many people must soon perish with famine in this place. Some families have laid in store of Provissions against a Siege. We are threatned that whilst the Out Lines are attacked wth a rising of the Inhabitants within, & fire & sword, a dreadful prospect before us, and you know how many & how dear are the objects of our care. The Lord preserve us all & grant us an happy Issue out of these troubles.

For several nights past, I have expected to be roused by the firing of Cannon. Tomorrow is Sunday, & we may hope for one day of rest, at present a Solemn dead silence reigns in the Streets, numbers have packed up their effects, & quited the Town, but the General has put a Stop to any more removing, & here remains in Town about 9000 Souls (besides the Servants of the Crown) These are the greatest Security, the General declared that if a Gun is fired within the Town the inhabitants shall fall a Sacrifice. Amidst our distress & apprehension, I am rejoyced our British Hero was preserved, My Lord Percy had a great many & miraculous escapes in the late Action. This amiable Young Nobleman with the Graces which attracts Admiration, possesses the virtues of the heart, & all those qualities that form the great Soldier --- Vigilent Active, temperate, humane, great Command of temper, fortitude in enduring hardships & fatigue, & Intrepidity in dangers. His Lordships behavior in the day of trial has done honor to the Percys. indeed all the Officers & Soldiers behaved with the greatest bravery it is said

I hope you and yours are all well & shall be happy to hear so. I woud beg of you whenever you write to mention the dates of my Letters which you have rec'd since you wrote specialy my last of March 2d

I am not able at present to write to our Dear friends at Chester woud desire the favor of you to write as soon as you receive this, & present my respects to your & my friends there, and likewise the same to those who are near to you.

I wrote not long ago both to Miss Tylston & to my Aunt H: --- have not heard yet from the Bahamas

Have never heard from Mr Gildart or Mr Earl yet

The Otter Man of War is just arrived Sunday Morng

What is marked with these Lines, you are at Liberty to make as publick as you please Let the merits of Lord Percy be known as far as you can.

1775: April 29

Christian Barnes to Elizabeth Inman

A known Loyalist, merchant Henry "Tory" Barnes was forced to leave his home in Marlborough, Massachusetts, to avoid capture. Terrified by the visit of a rebel soldier, Barnes's wife, Christian, described the incident to Elizabeth Inman (1726-1786), a Cambridge friend who shared her sympathies, if not her immediate peril. Along with hundreds of others who sympathized with the British, Henry Barnes would be officially banished from Boston in the fall.

It is now a week since I had a line from my dear Mrs. Inman, in which time I have had some severe trials, but the greatest terror I was ever thrown into was on Sunday last. A man came up to the gate and loaded his musket, and before I could determine which way to run he entered the house and demanded a dinner. I sent him the best I had upon the table. He was not contented, but insisted upon bringing in his gun and dining with me; this terrified the young folks, and they ran out of the house. I went in and endeavored to pacify him by every method in my power, but I found it was to no purpose. He still continued to abuse me, and said when he had eat his dinner he should want a horse and if I did not let him have one he would blow my brains out. He pretended to have an order from the General for one of my horses, but did not produce it. His language was so dreadful and his looks so frightful that I could not remain in the house, but fled to the store and locked myself in. He followed me and declared he would break the door open. Some people very luckily passing to meeting prevented his doing any mischief and staid by me until he was out of sight, but I did not recover from my fright for several days. The sound of drum or the sight of a gun put me into such a tremor that I could not command myself. I have met with but little molestation since this affair, which I attribute to the protection sent me by Col. Putnam and Col. Whitcomb. I returned them a card of thanks for their goodness tho' I knew it was thro' your interest I obtained this favor. . . . The people here are weary at [Mr. Barnes's] absence, but at the same time give it as their opinion that he could not pass the guards. . . . I do not doubt but upon a proper remonstrance I might procure a pass for him through the Camp from our two good Colonels. . . . I know he must be very unhappy in Boston. It was never his intention to quit his family. . . .

1775: Circa June 15

Sarah Deming to Sally Coverley

All we know about Sarah Winslow Deming (1722-1788) is that she was born in Massachusetts, the daughter of John and Sarah Winslow, and that, as this letter attests, she was a terrified witness to the very beginnings of the American Revolution. The troops she referred to were British, and this letter to her niece was a vivid reminder that the war would be fought not in far-off battlefields, but on the colonists' doorsteps.

General Thomas Gage was Britain's military governor of Massachusetts. Aceldama refers to the land Judas purchased with the money he received for betraying Christ; the word means "field of blood." The Sally Sarah referred to in the letter was a different niece; Lucinda was a servant.

My Dear Niece

I engaged to give you & by you your papa and mamma some account of my peregrinations with the reasons thereof. The cause is too well known to need a word upon it.

I was very unquiet from the moment I was informed that more troops were coming to Boston. 'Tis true that those who had wintered there, had not given us much molestation, but an additional strength I dreaded and determined if possible to get out of their reach, and to take with me as much of my little interest as I could. Your uncle Deming was very far from being of my mind from which has proceeded those diflcutics which peculiarly related to myself --- but I now say not a word of this to him; we are joint sufferers and no doubt it is God's will that it should be so.

Many a time have I thought that could I be out of Boston together with my family and my friends, I could be content with the meanest fare and slenderest accommodation. Out of Boston, out of Boston at almost any rate --- away as far as possible from the infection of smallpox & the din of drums & martial musick as it is called and horrors of war --- but my distress is not to be described --- I attempt not to describe it.

On Saterday the 15th April p.m. I had a visit from Mr. Barrow. I never saw him with such a countenance.

The Monday following, April 17, I was told that all the boats belonging to the men of war were launched on Saterday night while the town inhabitants were sleeping except some faithful watchmen who gave the intelligence. In the evening Mr. Deming wrote to Mr Withington of Dorchester to come over with his carts the very first fair day (the evening of this day promising rain on the next, which accordingly fell in plenty) to carry off our best goods.

On Tuesday evening 18 April we were informed that the companies above mentioned were in motion, that the men of war boats were rowed round to Charlestown ferry, Barton's point and bottom of ye common, that the soldiers were run thro the streets on tip toe (the moon not having risen) in the dark of ye evening, that there were a number of handcuffs in one of the boats, which were taken at the long wharf, & that two days provision had been cooked for 'em on board one of the transport ships lying in ye harbor. That whatever other business they might have, the main was to take possession of the bodies of Mess. Adams & Hancock whom they & we knew where they were lodged. We had no doubt of the truth of all this, and that expresses were sent forth both over the neck & Charlestown ferry to give our friends timely notice that they might escape. N.B. I did not git to bed this night till after 12 oclock, nor to sleep till long after that, and then my sleep was much broken as it had been for many nights before.

Early on Wednesday the fatal 19th April before I had quited my chamber one after another came running to tell me that the kings troops had fired upon and killed 8 of our neighbors at Lexington in their way to Concord.

All the intelligence of this day was dreadful. Almost every countenance expressing anxiety and distress: but description fails here. I went to bed about 12 o. c. this night, having taken but little food thro the day, having resolved to quit the town before the next setting sun, should life and limbs be spared me. Towards morning I fell into a profound sleep, from which I was waked by Mr. Deming between 6 and 7 o. c. informing me that I was Gen. Gage's prisoner all egress & regress being cut off between the town and the country. Here again description fails. No words can paint my distress --- I feel it at this instant (just eight weeks after) so sensibly that I must pause before I proceed.

1775: JUNE 20

LOIS PETERS TO NATHAN PETERS

Lois Crary Peters (1750-1837) and her husband, Nathan (1747-1824), were living in Preston, Connecticut, and Lois was pregnant with the fourth of their nine children when Nathan joined the Continental army to fight the British. Their separation, which was to last several years, left Lois in charge of the household as well as of her husband's saddle business.

The battle she mentioned was Bunker Hill, which had taken place (actually at nearby Breed's Hill) three days before.

Preston, June ye 20th at Night 1775

Dear husband

I this Moment Take Pen in Hand To Let you know that I am well and all our Friends here have No news To write wee have heard of the battle you have had Among you but wee hear So Many Storys wee no not what To believe a report This Morning was very Current here that Genll Putnum was Missing but we had it contradicted befor knigh and Said he was only Sligtily wounded in the wrist our fears are Many but wee all hope for the best My heart akes for you and all our friends there but I Keep up as good Spirits as possibel if you Could Spare your Mare Should bee very Glad you would Send her hom As Soon as possible for I Cant borrow at all and Should bee glad you would Send mee Some Money if you Can but Dont let that Troubel you for I am not Like To Suffer for any article To Support My family but Cannot Carry on The Trade without money but that is the Least of my Troubels at Present our Corn Looks well and our Woork goes on as well as I Could wish Pray write Every opportunity it being Late Must Coclude with wishing you the best of heavens blessing and hope that God in du Time will return you To your famely in Safty am your Loving wife Til Death

Lois Peters

1775: SEPTEMBER 21

MERCY OTIS WARREN TO JAMES WARREN

A writer who was friends with many key figures of the Revolution, Mercy Otis Warren (1728-1814) was a poet, dramatist, propagandist, and historian whose volumes about the war (published in 1805) would be among the first written and the most widely read. She was married to James Warren (1726-1808), a member of the Massachusetts legislature, known as the General Court. Managing their Plymouth home and four sons while James became president of Massachusetts's provisional Congress, Mercy offered a vivid portrait of family life that, despite its archaic language, conjures thoroughly timeless behavior.

The Warrens lived in Plymouth; the Congress usually met in Watertown, about forty miles away. The "sickly season" referred to the prevalent threat of smallpox. The Warrens' son Winslow was sixteen, Charles was thirteen, Henry was eleven, and George had just had his ninth birthday.

Just as I got up from dinner this day yours of the 15 & 18 came to hand; No desert was ever more welcome to a luxurious pallate, it was a regale to my longing mind: I had been eagerly looking for more than a week for a line from the best friend of my heart.

I had contemplated to spend a day or two with my good father, but as you talk of returning so soon I shall give up that and every other pleasure this world can give for the superior pleasure of your company. I thank you for the many expressions in yours which bespeak the most affectionate soul, or heart warmed with friendship & esteem which it shall ever be my assiduous care to merit. --- but as I am under some apprehensions that you will be again disappointed and your return postponed, I will endeavor to give you some account of the reception I met from our little family on my arrival among them after an absence which they thought long: your requesting this as an agreeable amusement is a new proof that the Father is not lost in the occupations of the statesman.

I found Charles & Henry sitting on the steps of the front door when I arrived --- they had just been expressing their ardent wishes to each other that mamah would come in before dinner when I turned the corner having our habitation. One of them had just finished an exclamation to the other "Oh what would I give if mamah was now in sight," you may easily judge what was their rapture when they saw their wishes instantly compleated.

The one leaped into the street to meet me --- the other ran into the house in an extacy of joy to communicate the tidings, & finding my children well at this sickly season you will not wonder that with a joy at least equal to theirs I ran hastily into the entry; but before I had reached the stair top was met by all the lovely flock. Winslow half affronted that I had delayed coming home so long & more than half happy in the return of his fond Mother, turned up his smiling cheek to receive a kiss while he failed in the effort to command the grave muscles of his countenance.

George's solemn brow was covered with pleasure & his grave features not only danced in smiles but broke into a real laugh more expressive of his heartfelt happiness than all the powers of language could convey and before I could sit down and lay aside my riding attire all the choice gleanings of the Garden were offered each one pressing before the other to pour the yellow produce into their mamah's lap.

Not a complaint was uttered --- not a tale was told through the day but what they thought would contribute to the happiness of their best friend; but how short lived is human happiness. The ensuing each one had his little grievance to repeat, as important to them as the laying an unconstitutional tax to the patriot or the piratical seazure of a ship & cargo, after much labour & the promising expectation of profitable returns when the voyage was compleat --- but the umpire in your absence soon accommodated all matters to mutual satisfaction and the day was spent in much cheerfulness encircled by my sons. . . . My heart has just leaped in my bosom and I ran to the stairs imagining I heard both your voice & your footsteps in the entry. Though disappointed I have no doubt this pleasure will be realized as soon as possible by

Your affectionate

M. Warren

1775: OCTOBER 2

DEBORAH CHAMPION TO PATIENCE

Deborah Champion (1753-?) was the daughter of the Continental army's commissary general, Henry Champion. From Westchester, Connecticut, she rode to Boston carrying messages from her father to General George Washington. Her recounting of that adventure in this letter to a friend is filled with patriotism as well as a touching kind of wonder at her own courage.

Linsey-woolsey was a blend of linen and wool often used for blankets and scarves. A close silk hood was one that fit tightly. A calash was an oversized bonnet that was apparently not a favorite fashion of the younger generation

Westchester, Conn.

Oct. 2nd, 1775.

My dear Patience,

I know you are thinking it a very long time since I have written you, and indeed I would answered your last, sweet letter long before now, but I have been away from home. Think of it, and to Boston. I know you will hardly believe that such a stay-at-home as I should go, and without my parents too. Really and truly I have been.

It happened last month, and I have only been home ten days, hardly long enough to get over the excitement. Before you suffer too much with curiosity and amazement I will hasten to tell you about it. A few days after receiving your letter I had settled myself to spend a long day at my spinning being anxious to get the yarn ready for some small clothes for father. Just as I was busily engaged I noticed a horseman enter the yard, and knocking at the door with the handle of his whip, heard him ask for Colonel Champion, and after brief converse with my father, he entered the house.

Soon after my mother came to me and asked me to go to the store in town and get her sundry condiments, which I was very sure were already in the storeroom. Knowing that I was to be sent out of the way, there was nothing left for me, but to go, which I accordingly did, not hurrying myself you may be sure. When I returned the visitor was gone but my father was walking up and down the long hall and with hasty steps and worried and perplexed aspect.

You know father has always been kind and good to me, but none know better than you the stern self repressment our New England character engenders, and he would have thought it unseemly for his child to question him, so I passed on into the family-room, to find mother and deliver my purchases. My father is troubled, is aright amiss, I asked. "I cannot say, Deborah," she replied, "You know he has many cares and the public business presses heavily just now. It may be he will tell us." Just then my father stood in the door way. "Wife, I would spake with you." Mother joined him in the keeping-room and they seemed to have long and anxious conversation. I had gone back to my spinning but could hear the sound of their voices. Finally I was called to attend them, to my astonishment.

Father laid his hand on my shoulder, (a most unusual caress with him) and said almost solemnly, "Deborah I have need of thee. Hast thee the courage to go out and ride, it may be even in the dark and as fast as may be, till thou comest to Boston town?" He continued, "I do not believe Deborah, that there will be actual danger to threaten thee, else I would not ask it of thee, but the way is long, and in part lonely. I shall send Aristarchus with thee and shall explain to him the urgency of the business. Though he is a slave, he understands the mighty matters at stake, and I shall instruct him yet further. There are reasons why it is better for you a woman to take the despatches I would send than for me to entrust them to a man; else I should send your brother Henry. Dare you go?"

"Dare, father, and I your daughter? A chance to do a service for my country and for General Washington; --- I am glad to go."

So dear Patience it was settled we should start in the early morning of the next day, father needing some time to prepare the paper. You remember Uncle Aristarchus; he has been devoted to me since my childhood, and particularly since I made a huge cask to grace his second marriage, and found a name for the dusky baby, which we call Sophranieta. He has unusual wits for a slave and father trusts him. Well, to proceed, --- early the next morning, before it was fairly light, mother called me, though I had seemed to have hardly slept at all. I found a nice hot breakfast ready and a pair of saddle bags packed with such things as mother thought might be needed. When the servants came in for prayer I noticed how solemn they looked and that Aunt Chloe, Uncle Aristarchus' wife, had been crying. Then I began to realize I was about to start on a solemn journey, you see it was a bright sunshiny morning and the prospect of a long ride, the excitement of what might happen had made me feel like singing as I dressed. I had put on my linsey-woolsey dress, as the roads might at times be dusty and the few articles I needed made only a small bundle.

Father read the 91st Psalm, and I noticed that his voice trembled as he read "He shall give His Angels charge over thee," and I knew into whose hands he committed me. Father seemed to have everything planned out and to have given full instructions to Uncle Aristarchus. We were to take the two carriage horses for the journey was too long for one horse to take us both, I riding on a pillion. John and Jerry are both good saddle horses as you and I know.

The papers that were the object of the journey I put under my bodice, and fastened my neckerchief securely down. Father gave me also a small package of money. You know our Continental bills are so small you can pack away a hundred dollars very compactly. Just as the tall clock in the hall was striking eight, the horses were at the door. I mounted putting on my camlet cloak for the air was yet a little cool. Mother insisted on my wearing my close silk hood and taking her calash. I demurred a little, but she tied the strings together and hung it on my arm, saying, "Yes daughter". Later I understood the precaution. Father again told me of the haste with which I must ride and the care to use for the safety of the despatches, and we set forth with his blessing. Uncle Aristarchus looked very pompous, as if he was Captain and felt the responsibility.

The British were at Providence in Rhode Island, so it was thought best for us to ride due north to the Massachusetts line and then east as best we could. The weather was perfect, but the roads were none too good as there had been recent rains, but we made fairly good time going through Norwich then up the Valley of the Quinnebaugh to Canterbury where we rested our horses for an hour, then pushed on hoping to reach Pomfret before dark. At father's desire I was to stay at Uncle Jerry's the night, and if needful get a change of horses. All went well as I could expect. We met few people on the road. Almost all the men are with the army, so we saw only old men, women and children on the road or in the villages.

Oh! War is a terrible and cruel thing. Uncle Jerry thought we had better take fresh horses in the morning and sun up found us on our way again. Aunt Faith had a good breakfast for us --- by candle light. We got our meals after that at some farm house generally. I left that to Uncle Starkey. As it neared hungry time he would select a house, ride ahead, say something to the woman or old man and whatever it was he said seemed magical, for as I came up I would be met with smiles, kind words "God bless you" and looks of wonder. The best they had was pressed on us, and they were always unwilling to take pay which we offered. Everywhere we heard the same thing, love for the Mother Country, but stronger than that, that she must must give us our rights, that we were fighting not for independence, though that might come and would be the war-cry if the oppression of unjust taxation was not removed. Nowhere was a cup of imported tea offered us. It was a glass of milk, or a cup of "hyperion" the name they gave to a tea made of raspberry leaves. We heard that it would be almost impossible to avoid the British, unless by going so far out of the way that too much time would be lost, so plucked up what courage I could as darkness began to come on at the close of the second day. I secreted the papers in a small pocket in a saddle bag under some of the eatables that mother had put up. We decided to ride all night. Providentially the moon just past full, rose about 8 o'clock and it was not unpleasant, for the roads were better. I confess that I began to be weary. It was late at night or rather very early in the morning, that I heard a sentry call and knew that if at all the danger point was reached. I pulled my calash as far over my face as I could, thanking my wise mother's forethought, and went on with what boldness I could muster. I really believe I heard Aristarchus' teeth chatter as he rode to my side and whispered "De British missus for sure." Suddenly I was ordered to halt. As I could not help myself I did so. A soldier in a red coat appeared and suggested that I go to headquarters for examination. I told him "It was early to wake his Captain and to please let me pass for I had been sent in urgent haste to see a friend in need," which was true, if a little ambiguous. To my joy he let me go saying "Well, you are only an old woman any way." Evidently as glad to be rid of me as I of him. Would you believe me --- that was the only exciting adventure in the whole ride.

Just as I finished that sentence father came into my room and said "My daughter if you are writing of your journey, do not say just how or where you saw General Washington, nor what you heard of the affairs of the Colony. A letter is a very dangerous thing these days and it might fall into strange hands and cause harm. I am just starting in the chaise for Hartford to see about some stores for the troops, I shall take the mare as the other horses need rest." What a wise man my father is. I must obey, but I can say I saw General Washington. I felt very humble as I crossed the threshold of the room where he sat in converse with other gentlemen, one evidently an officer. Womanlike I wished that I had on my Sunday gown. I had put on a clean kerchief. I gave him the paper, which from his manner I judged to be of great importance. He was pleased to compliment me most highly on what he called my courage and my patriotism.

Oh, Patience what a man he is, so grand, so kind, so noble. I am sure we shall not look to him in vain as our leader.

Well, here I am home again safe and sound and happy to have been of use. We took a longer way home as far as Uncle Jerry's, so met with no mishap.

I hope I have not tired you with this long letter. Mother desires to send her love.

Yours in the bonds of love.

Deborah

P.S. I saw your brother Samuel in Boston. He sent his love if I should be writing you.

1775: NOVEMBER 27

ABIGAIL ADAMS TO JOHN ADAMS

Eloquent, feisty, intelligent, and politically informed, Abigail Smith Adams (1744-1818) would have been one of the great women of any era. She was the wife of one president, John Adams (1735-1826), and, though she didn't live to see him elected, the mother of another. At the time this letter was written, John was in Philadelphia at the Continental Congress, and Abigail was in Quincy at the family home. Her questions are a poignant reminder of the extent to which America's future remained an open question.

James Warren was Mercy Warren's husband (see page 23).

27 November, 1775

Colonel Warren returned last week to Plymouth, so that I shall not hear any thing from you until he goes back again, which will not be till the last of this month. He damped my spirits greatly by telling me, that the Court had prolonged your stay another month. I was pleasing myself with the thought, that you would soon be upon your return. It is in vain to repine. I hope the public will reap what I sacrifice.

I wish I knew what mighty things were fabricating. If a form of government is to be established here, what one will be assumed? Will it be left to our Assemblies to choose one? And will not many men have many minds? And shall we not run into dissensions among ourselves?

I am more and more convinced, that man is a dangerous creature; and that power, whether vested in many or a few, is ever grasping, and, like the grave, cries "Give, give." The great fish swallow up the small; and he, who is most strenuous for the rights of the people, when vested with power is as eager after the prerogatives of government. You tell me of degrees of perfection to which human nature is capable of arriving, and I believe it, but, at the same time, lament that our admiration should arise from the scarcity of the instances.

The building up a great empire, which was only hinted at by my correspondent, may now, I suppose, be realized even by the unbelievers. Yet, will not ten thousand difficulties arise in the formation of it? The reins of government have been so long slackened, that I fear the people will not quietly submit to those restraints, which are necessary for the peace and security of the community. If we separate from Britain, what code of laws will be established? How shall we be governed, so as to retain our liberties? Can any government be free, which is not administered by general stated laws? Who shall frame these laws? Who will give them force and energy? It is true, your resolutions, as a body, have hitherto had the force of laws; but will they continue to have?

When I consider these things, and the prejudices of people in favor of ancient customs and regulations, I feel anxious for the fate of our monarchy or democracy, or whatever is to take place. I soon get lost in a labyrinth of perplexities; but, whatever occurs, may justice and righteousness be the stability of our times, and order arise out of confusion. Great difficulties may be surmounted by patience and perseverance.

I believe I have tired you with politics; as to news we have not any at all. I shudder at the approach of winter, when I think I am to remain desolate.

I must bid you good night; 'tis late for me, who am much of an invalid. I was disappointed last week in receiving a packet by the post, and, upon unsealing it, finding only four newspapers. I think you are more cautious than you need be. All letters, I believe, have come safe to hand. I have sixteen from you, and wish I had as many more.

Adieu, yours

1776: MARCH 31

ABIGAIL ADAMS TO JOHN ADAMS

Separated from John for long stretches of time while he worked with the Continental Congress, Abigail Adams honed her letter-writing skills, which were nowhere more evident than in this famous epistle, with its memorable admonition to "Remember the Ladies." Her relatively upbeat tone reflects the fact that the British had abandoned Boston just two weeks earlier. Several weeks later, John would respond: "We know better than to repeal our Masculine systems. . . . in Practice you know We are the subjects. We have only the Name of Masters, and rather than give up this, which would compleatly subject Us to the Despotism of the Peticoat, I hope General Washington, and all our brave Heroes would fight."

John Murray, Lord Dunmore, was the royal governor of Virginia; weeks after Abigail wrote this letter, Dunmore would declare martial law in that colony and offer freedom to all slaves who would fight for the British. Mr. Crane, Mr. Trot, Becky Peck, Tertias Bass, and Mr. Reed were neighbors. "Your President" was John Hancock. Samuel Quincy was solicitor general. "Gaieti de Coar" was a misspelling of gaieté de coeur, meaning "happiness of the heart." Betsy Cranch was Abigail's niece. Saltpeter, also known as niter, was used for gunpowder and was also rumored to suppress sexual desire when taken orally.

Braintree March 31 1776

I wish you would ever write me a Letter half as long as I write you; and tell me if you may where your Fleet are gone? What sort of Defence Virginia can make against our common Enemy? Whether it is so situated as to make an able Defence? Are not the Gentery Lords and the common people vassals, are they not like the uncivilized Natives Brittain represents us to be? I hope their Riffel Men who have shewen themselves very savage and even Blood thirsty; are not a specimen of the Generality of the people.

I am willing to allow the Colony great merrit for having produced a Washington but they have been shamefully duped by a Dunmore.

I have sometimes been ready to think that the passion for Liberty cannot be Eaquelly Strong in the Breasts of those who have been accustomed to deprive their fellow Creatures of theirs. Of this I am certain that it is not founded upon that generous and christian principal of doing to others as we would that others should do unto us.

Do not you want to see Boston; I am fearfull of the small pox, or I should have been in before this time. I got Mr. Crane to go to our House and see what state it was in. I find it has been occupied by one of the Doctors of a Regiment, very dirty, but no other damage has been done to it. The few things which were left in it are all gone. Crane has the key which he never deliverd up. I have wrote to him for it and am determined to get it cleand as soon as possible and shut it up. I look upon it a new acquisition of property, a property which one month ago I did not value at a single Shilling, and could with pleasure have seen it in flames.

The Town in General is left in a better state than we expected, more oweing to a percipitate flight than any Regard to the inhabitants, tho some individuals discoverd a sense of honour and justice and have left the rent of the Houses in which they were, for the owners and the furniture unhurt, or if damaged sufficient to make it good.

Others have committed abominable Ravages. The Mansion House of your President is safe and the furniture unhurt whilst both the House and Furniture of the Solisiter General have fallen a prey to their own merciless party. Surely the very Fiends feel a Reverential awe for Virtue and patriotism, whilst they Detest the paricide and traitor.

I feel very differently at the approach of spring to what I did a month ago. We knew not then whether we could plant or sow with safety, whether when we had toild we could reap the fruits of our own industery, whether we could rest in our own Cottages, or whether we should not be driven from the sea coasts to seek shelter in the wilderness, but now we feel as if we might sit under our own vine and eat the good of the land.

I feel a gaieti de Coar to which before I was a stranger. I think the Sun looks brighter, the Birds sing more melodiously, and Nature puts on a more chearfull countanance. We feel a temporary peace, and the poor fugitives are returning to their deserted habitations.

Tho we felicitate ourselves, we sympathize with those who are trembling least the Lot of Boston should be theirs. But they cannot be in similar circumstances unless pusilanimity and cowardise should take possession of them. They have time and warning given them to see the Evil and shun it. --- I long to hear that you have declared an independancy --- and by the way in the new Code of Laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make I desire you would Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could. If perticuliar care and attention is not paid to the Laidies we are determined to foment a Rebelion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.

That your Sex are Naturally Tyrannical is a Truth so thoroughly established as to admit of no dispute, but such of you as wish to be happy willingly give up the harsh title of Master for the more tender and endearing one of Friend. Why then, not put it out of the power of the vicious and the Lawless to use us with cruelty and indignity with impunity. Men of Sense in all Ages abhor those customs which treat us only as the vassals of your Sex. Regard us then as Beings placed by providence under your protection and in immitation of the Supreem Being make use of that power only for our happiness.

April 5

Not having an opportunity of sending this I shall add a few lines more; tho not with a heart so gay. I have been attending the sick chamber of our Neighbour Trot whose affliction I most sensibly feel but cannot discribe, striped of two lovely children in one week. Gorge the Eldest died on wednesday and Billy the youngest on fryday, with the Canker fever, a terible disorder so much like the thr[o]at distemper, that it differs but little from it. Betsy Cranch has been very bad, but upon the recovery. Becky Peck they do not expect will live out the day. Many grown person are now sick with it, in this [street?]. It rages much in other Towns. The Mumps too are very frequent. Isaac is now confined with it. Our own little flock are yet well. My Heart trembles with anxiety for them. God preserve them.

I want to hear much oftener from you than I do. March 8 was the last date of any that I have yet had. --- You inquire of whether I am making Salt peter. I have not yet attempted it, but after Soap making believe I shall make the experiment. I find as much as I can do to manufacture cloathing for my family which would else be Naked. I know of but one person in this part of the Town who has made any, that is Mr. Tertias Bass as he is calld who has got very near an hundred weight which has been found to be very good. I have heard of some others in the other parishes. Mr. Reed of Weymouth has been applied to, to go to Andover to the mills which are now at work, and has gone. I have lately seen a small Manuscrip de[s]cribing the proportions for the various sorts of powder, fit for cannon, small arms and pistols. If it would be of any Service your way I will get it transcribed and send it to you. --- Every one of your Friend[s] send their Regards, and all the little ones. Your Brothers youngest child lies bad with convulsion fitts. Adieu. I need not say how much I am Your ever faithfull Friend.

1776: JULY 21

ABIGAIL ADAMS TO JOHN ADAMS

The formal signing of the Declaration of Independence did not take place until August. In the meantime, the document was widely published, and Abigail duly recorded one of its many public readings in a short, joyous letter to John.

Colonel Thomas Crafts headed several artillery regiments. James Bowdoin was a member of the Massachusetts executive council. Abigail's second paragraph was about a plot to assassinate George Washington that was rumored to have involved the mayor and governor of New York, as well as Washington's guard, Thomas Hickey, who on June 28 was hanged for treason. The "George" she mentioned was the king, and the line she quoted is from Alexander Pope's Essay on Man: "If plagues or earthquakes break not Heav'n's design, / Why then a Borgia, or a Catiline?"

Boston, 21 July, 1776

Last Thursday, after hearing a very good sermon, I went with the multitude into King Street to hear the Proclamation for Independence read and proclaimed. Some field-pieces with the train were brought there. The troops appeared under arms, and all the inhabitants assembled there (the small-pox prevented many thousands from the country), when Colonel Crafts read from the balcony of the State House the proclamation. Great attention was given to every word. As soon as he ended, the cry from the balcony was, "God save our American States," and then three cheers which rent the air. The bells rang, the privateers fired, the forts and batteries, the cannon were discharged, the platoons followed, and every face appeared joyful. Mr. Bowdoin then gave a sentiment, "Stability and perpetuity to American independence." After dinner, the King's Arms were taken down from the State House, and every vestige of him from every place in which it appeared, and burnt in King Street. Thus ends royal authority in this state. And all the people shall say Amen.

I have been a little surprised that we collect no better accounts with regard to the horrid conspiracy at New York; and that so little mention has been made of it here. It made a talk for a few days, but now seems all hushed in silence. The Tories say that it was not a conspiracy, but an association. And pretend that there was no plot to assassinate the General. Even their hardened hearts feel --- --- --- the discovery --- --- --- we have in George a match for "a Borgia or a Catiline" --- a wretch callous to every humane feeling. Our worthy preacher told us that he believed one of our great sins, for which a righteous God has come out in judgment against us, was our bigoted attachment to so wicked a man. May our repentance be sincere.

1776: AUGUST 19

ABIGAIL GRANT TO AZARIAH GRANT

By the summer of 1776, the fighting between the British and the colonists had been going on for more than a year, and it would continue on land and at sea until the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783. Anywhere from two hundred thousand to twice that number of American colonial men would fight at one point or another (estimates vary greatly, as many men enlisted more than once). But the fighting, as this letter from a wife to her husband suggests, was not always done in the most heroic fashion.

The original of this letter has not been found; the text below comes from a copy that was discovered among the papers of an old Connecticut family and reprinted in a nineteenth-century collection.

August ye 19th a.d. 1776

Loving Husband

after Love to I would inform you that we are well through Gods mercy upon us and through the Same Mercy I hope these Lines will find you well also I keep riting to you again & again & never can have only one Letter from you tho I hear by Captn Wm Riley news that makes me very Sorry for he Says you proved a Grand Coward when the fight was at Bunkers hill & in your Surprise he reports that you threw away your Cartridges So as to escape going into the Battle I am loath to believe it but yet I must unless you will write to me & inform me how it is, And if you are afraid pray own the truth & come home & take care of our Children & I will be Glad to Come & take your place, & never will be Called a Coward, neither will I throw away one Cartridge but exert myself bravely in so good a Cause. So hopeing you will let me know how it is, & how you do, So bidding you farewell, wishing you the best of heavens Blessings & a Safe & manlike return, subscribing myself your Loveing wife untill Death

Abigail Grant

1776: NOVEMBER 25

MERCY OTIS WARREN TO JAMES WARREN

Smallpox was the second great enemy of the Revolutionary era. Introduced to North America in the sixteenth century by Spanish conquistadors, it flourished with every war and by 1775 had become a full-scale epidemic. Estimates are that more than 130,000 North Americans, most of them Indians, were killed by smallpox during the Revolution. Being directly inoculated --- an option available almost exclusively to wealthy white colonists --- was only slightly less dangerous than catching smallpox naturally, and mothers like Mercy Warren (see page 23) who could actually afford the procedure for their children were terrified by it nonetheless.

Plimouth 25 Nov 1776.

The letter my dear Mr. Warren will receive tomorrow I almost ish I had not wrote. I own I was a litle too Low spirited, but my mind was oppressed & I wanted to unbosom. it is this evening no less free from care though I feel a little Differently. I was ready to think the task of Governing & Regulating my Children alone almost too much --- I now am forced to strive hard to keep out the Gloomy apprehension that the Burden may soon be lessened in some painful way. I have been this afternoon at the hospital where I left your three youngest sons. Poor Children --- it was not possible to make them willing to give up the project. they thought it a mighty priviledge to be innoculated. I wish nor they nor we may have Reason to Regret it --- but I cannot feel quite at Ease --- I Want to Discourage Winslow from going in yet am afraid. Their accomodations are not altogether to my liking nor are their Nurses sufficient but they talk of getting more & better --- but if my dear Children should be very ill I must go & take Charge of them myself Inconvenient as it is --- 48 persons were innoculated this afternoon & near as many will offer to-morrow. I think it is too many for one Class. But there they are --- & it is as easy for the Great phisition of soul & Body to Lend Healing Mercy to the Multitude as to the Few, and if He Brings them Back in safty to their several Habitations I hope we shall Adore the Hand that Heals, and give Glory to the Rock of our salvation.

Wensday 24 of Nov. Your house Looks Lonely and Deserted in a manner you can hardly conceive --- but three or four weeks will soon run away & if my family should then be Returned in safty to my own Roof I shall be thankful Indeed.

1777: JANUARY 4

ELIZABETH INMAN TO JOHN INNES CLARK

Born in Scotland, Elizabeth Murray Inman (see page 18) came to America with her two brothers when she was twelve. In Boston, she became a successful shop owner, embroidery instructor, and landlord. She was widowed twice; Ralph Inman, a retired businessman, was her third husband. She had no children herself, but she convinced her relatives in England to send her their children as apprentices in business. Like other British Loyalists, Inman experienced the War for Independence as a civil war. In this letter, she urged a friend, Providence merchant John Innes Clark, not to permit her nephew John Murray to join the American rebels.

Whether John joined or not is unknown. Joseph Nightingale as Clark's business partner.

Boston, January 4th, 1777.

Dear Sir, ---

Words are wanting to express my surprise and concern at reading J. Murrays letter by Mr. Sherry. I hope I never have nor never will give so much pain to an enemy as this does to me who has gloried in thinking I was his Aunt and friend. I have ever been proud of your Candor, generosity, Humanity, friendship and affection to me. I now rely on these good qualities and your promise. If your and Mr. Nightengale's authority is not sufficient to Check this youth I beg you'll make an errand for him to Boston. When I took him from his Fathers House I looked on myself as accountable to Him for the boy till he arrived at the age of 21. At that time I intended to advise him to visit his family and consult with them about settling. If he determins on taking up arms against them, farewell to his Fathers and Mothers happiness. They will bid adieu to their eldest darling Son and end their days in sorrow. Their fondness for him made them expect he would be the stay of the large family and the support of their old age. How blasted then their hopes. For God's sake let it not be. Assist me in Clearing him. Consider you have children, tho' young; you do not like disabedience in them, how would oposition like this affect you.

My respects to your Ladys. I expected to see them before Christenmas. Their company will give me pleasure.

Adieu.

* *

1777: MAY 22

ANNE CHRISTIAN TO PATRICK HENRY

Among revolutionary figures, Patrick Henry (1736-1799) distinguished himself as a lawyer, an orator ("give me liberty or give me death!"), a delegate to the Continental Congress, and by 1776, as Virginia's first governor. Perhaps slightly less attracted to sacrifice, his sister Anne Henry Christian (1740?-1790?) was miserable without her husband, William, then a representative in the Virginia legislature. In this letter, Anne asked her big brother to use his influence to have her husband sent home.

It is unlikely that Anne succeeded, as in June, William as still in Tennessee, helping to conclude a treaty with the Cherokee.

Haw Bottom, May 22d, 1777.

My Dear Brother:

Mr Christian has, I suppose, informed you of my intended Journey down being stopt, which deprives me of the pleasure of seeing you for a while; indeed our Family & cares increase so fast, that God knows when I shall be able to take another journey to see my dear friends below. Indeed Mr Christian is so much abroad that I am more confined on that account. I wish my dear brother could, by any means, be instrumental towards his quitting the public employment that he is engaged in, if it were only for a while, until he could get his affairs brought into some better way than at present. Cannot you assist in doing me this great favor? I am heartily sorry to trouble you on any domestic business, but I know you will excuse me. Some one certainly may be had that would answer as well to act in his place for the future, & at the same time save a whole family from ruin, as his stay at home might yet do; this is the case, & I am sorry to see that he is entering from one thing to another without considering his private affairs, which are almost desperate, & again I must entreat you to have some private conversation with him. . . . I hope you can find a few leisure moments to oblige a sister ho is, & ever will be, Your ever affect.

A. Christian.

P.S. Shall I never be so happy as to see you up here. I have much to say but would not trouble you with a long letter, necessity urges me to say the above.

* * *

1777: AUGUST 23

LUCY KNOX TO HENRY KNOX

Lucy Flucker Knox (1756-1824) had been married just three years when she sent this letter to her husband, Henry (1750-1806), one of George Washington's most trusted military leaders and the nation's first secretary of war. Writing from Boston, Lucy gave a lonely picture of her life, mourning particularly her "lost" family members, who, as British Loyalists, had been forced to flee the city.

The couple would have thirteen children, only three of hom lived to be adults; "Little Lucy" was their first.

My dearest friend

I wrote you a line by the last post just to let you know I was alive, which…was all I could then say with propriety for I had serious thoughts that I never should see you again, so much was I reduced by only four days of illness but by help of a good constitution I am surprisingly better today. I am now to answer your three last letters in one of which you ask for a history of my life. It is my love barren of adventure and replete with repetition that I fear it will afford you little amusement. How such as it is I give to you. In the first place, I rise about eight in the morning so late an hour you will say but the day after that is full long for a person in my condition. I presently after sit down to my breakfast, where a page in my book and a dish of tea, employ me alternately for about an hour. When after seeing that family matters go on right, I repair to my work…for the rest of the forenoon. At two o'clock I usually take my solitary dinner where I reflect upon my past happiness. I used to sit at the window watching for my Harry, and when I saw him coming my heart would leap for joy hen he was at my own side and never happy apart from me when the bare thought of six months absence would have shook him. To divert Alex's pleas I place my little Lucy by me at table, but the more engaging her little actions are so much the more do I regret the absence of her father who would take such delight in them. In the afternoon I commonly take my chaise and ride into the country or go to drink tea with one of my few friends . . . then with any. . . . I often spend the evening, but when I return home how [to] describe my feelings to find myself entirely alone, to reflect that the only friend I have in the orld is such an immense distance from me to think that he may be sick and I cannot assist him. My poor heart is ready to burst, you who know what a trifle would make me unhappy can conceive what I suffer now. When I seriously reflect that I have lost my father, mother, brother, and sisters entirely lost them I am half distracted. . . . I have not seen him for almost six months, and he writes me without pointing at any method by which I may ever expect to see him again. Tis hard my Harry indeed it is I love you with the tenderest the purest affection. I would undergo any hardship to be near you and you will not let me. . . . The very little gold we have must be reserved for my love in case he should be taken. . . . [A person] if he understands business he might without capital make a fortune --- people here without advancing a shilling frequently clear hundreds in a day, such chaps as Eben Oliver are all men of fortune while persons who have ever lived in affluence are in danger of want and that you had less of the military man about you, you might then after the war have lived at ease all the days of your life, but now, I don't know what you will do, you being long accustomed to command --- will make you too haughty for mercantile matters --- tho I hope you will not consider yourself as commander in chief of your own house --- but be convinced tho not in the affair of Mr. Coudoe that there is such a thing as equal command.

I send this by Capt. Randal who says he expects to remain with you --- pray how many of those lads have have you --- I am sure they must be very expensive --- I am in want of some square dollars --- which I expect from you --- to by me a peace of linen, an article I can do no longer without haveing had no recruit of that kind for almost five years. Girls in general when they marry, are wed stocked with those things but poor I had no such advantage.

Little Lucy who is without exception the sweetest child in the orld --- sends you a kiss --- but where shall I take it from say you --- from the paper I hope --- but dare I say I sometimes fear that a long absence the force of bad example may lead you to forget me at sometimes. To know that it ever gave you pleasure to be in company with the finest woman in the world, would be worse than death to me --- but it is not so, my Harry is too just, too delicate, too sincere --- and too fond of his Lucy to admit the most remote thought of that distracting kind --- away with it --- don't be angry with me my Love --- I am not jealous of your affection --- I love you with a love as true and sacred as ever entered the human heart --- but from a diffidence of my own merit I sometimes fear you will Love me less after being so long from me --- if you should, may my life end before I know it, that I may die thinking you holly mine.

Adieu my Love

LK

* *

1777: SEPTEMBER 22

ALICE LEE SHIPPEN TO NANCY SHIPPEN

Alice Lee Shippen (1736-1817) was evidently a oman on the edge when she sent this letter from Philadelphia to her fourteen-year-old daughter, Anne Hume Shippen (1763-1841), nicknamed Nancy. Though the war was clearly on Alice's mind, its threats did not stop her from urging her daughter to mind her manners, keep up with her sewing, and pursue all manner of self-improvements.

Mrs. Rogers ran Nancy's boarding school, in Trenton, New Jersey, less than fifty miles from the recent landing of British troops at Elizabeth. Alice was married to William Shippen, head of the Continental army's hospital, and as the sister of Richard Henry Lee and Francis Lightfoot Lee, both signers of the Declaration. Dimity is a sheer cotton fabric.

My dear Nancy

I was extremely surprized when the waggon return'd the other evening without one line from you after I had been at the trouble & expence of sending for you as soon as I was inform'd 4000 troops were landed in Elizabeth-Town. Surely you should not omit any opportunity of writing to me, but to neglect such a one was inexcusable, but I shall say the less to you now, because you have been taught your duty & I take it for granted Mrs. Rogers has already reproved you for so great an omission, but do remember my dear how much of the beauty & usefulness of life depends on a proper conduct in the several relations in life, & the sweet peace that flows from the consideration of doing our duty to all with whom we are conected. I am sorry it is not in my power to get you the things I promised. It was late before I got to Philadelphia the afternoon I left you & the shops were shut the next day. I have looked all over this place but no muslin, satin or dimity can be got. However your Uncle Joe says he has a hole suit of dimity very fine & that you may have what you want. Get enough for two ork bags one for me & the other for yourself.

Your Pappa thinks you had better work a pr. of ruffles for General Washington if you can get proper muslin. Write to me as soon as you receive this & send your letter to your Pappa. Tell me how you improve in your work. Needle work is a most important branch of a female education, & tell me how you have improved in holding your head & sholders, in making a curtsy, in going out or coming into a room, in giving & receiving, holding your knife & fork, walking & seting. These things contribute so much to a good appearance that they are of great consequence. Perhaps you will be at a loss how to judge wether you improve or not, take this rule therefore for your assistance. You may be sure you improve in proportion to the degree of ease with hich you do any thing as you have been taught to do it, & as you may be partial to yourself as to your appearance of ease (for you must not only feel easy but appear so) ask Mrs. Rogers opinion as a friend who now acts for you in my place & you must look upon her as your parent as well as your Governess as you are at this time wholy in her care & you may depend upon it if you treat her with the duty & affection of a child she ill have the feelings of a parent for you. Give my compliments to her & tell her I thank her for the care she takes of you. Give my compliments to the young Ladies. I am sorry Miss Stevens has left you. Dont offend Miss Jones by speaking against the Quakers. Tell Polly I shall remember her when I return. There is an alarm here the enemy are said to be coming this way, tis lucky you are not with me. Your Uncle F. Lee & his Lady & Mr. & Mrs. Haywood are with me in the same house. They set out today for Lancaster & I for Maryland. I believe I will write to you as soon as I get settled. Farewell my dear. Be good & you will surely be happy which will contribute very much to the happiness of

Your Affect. Mother

1777: OCTOBER 19

SALLY WISTER TO DEBORAH NORRIS

Sally Wister (1761-1804) and Deborah Norris (1761-1839) grew up in Philadelphia and shared Quaker backgrounds, well-to-do upbringings, friends, school, and dozens of teenage intimacies. When Wister's family, fearing a direct attack, moved to a farmhouse fifteen miles from the city, the girls began putting their secrets on paper. At the time Wister wrote this gossipy account, the British had just roundly defeated the Continental army at the Battle of Brandywine. But the potential danger to her family and the frequent visits and occasional quartering of rebel officers only seemed to encourage Wister's sense of romance.

"Second Day" was Tuesday in the Quaker week. Liddy, "Cousin P.," "Aunt F.," and Jesse were all members of the Foulke family, with whom the Wisters were staying. Sally's younger sister, Elizabeth, as called Betsy. "G. E." was George Emlen, husband of Sally's friend's sister. General William Smallwood commanded the Maryland troops. This letter as written as part of a journal addressed to Deborah Norris.

Second Day, October 19th

To Deborah Norris ---

Now for new and uncommon scenes. As I was lying in bed, and ruminating on past and present events, and thinking how happy I should be if I could see you, Liddy came running into the room, and said there was the greatest drumming, fifing, and rattling of waggons that ever she had heard. What to make of this we were at a loss. e dress'd and down stairs in a hurry. Our wonder ceased. The British had left Germantown, and our army were marching to take possession. It was the general opinion they ould evacuate the capital. Sister B. and myself, and G. E. went about half a mile from home, where we cou'd see the army pass. Thee will stare at my going, but no impropriety, in my opine, or I should not have gone. We made no great stay, but return'd with excellent appetites for our breakfast. Several officers call'd to get some refreshments, but none of consequence till the afternoon. Cousin P. and myself ere sitting at the door; I in a green skirt, dark short gown, etc. Two genteel men of the military order rode up to the door: "Your servant, ladies," etc.; ask'd if they could have quarters for General Smallwood. Aunt F. thought she could accommodate them as well as most of her neighbors, --- said they could. One of the officers dismounted, and wrote "Smallwood's Quarters" over the door, which secured us from straggling soldiers. After this he mounted his steed and rode away. When we were alone, our dress and lips were put in order for conquest, and the hopes of adventures gave brightness to each before passive countenance. . . . Dr. Gould usher'd the gentlemen into our parlour, and introduc'd them, --- "General Smallwood, Captain Furnival, Major Stodard, Mr. Prig, Captain Finley, and Mr. Clagan, Colonel Wood, and Colonel Line." These last two did not come with the General. They are Virginians, and both indispos'd. The General and suite, are Marylanders. Be assur'd, I did not stay long with so many men, but secur'd a good retreat, heart-safe, so far. Some sup'd with us, others at Jesse's. They retir'd about ten, in good order. How new is our situation! I feel in good spirits, though surrounded by an army, the house full of officers, the yard alive with soldiers, --- very peaceable sort of people, tho'. They eat like other folks, talk like them, and behave themselves with elegance; so I will not be afraid of them, that I won't. Adieu. I am going to my chamber to dream, I suppose, of bayonets and swords, sashes, guns, and epaulets.

EXCHANGE

1778

SARAH HODGKINS AND JOSEPH HODGKINS

Joseph Hodgkins (1743-1829) was a cobbler who lived in Ipswich, Massachusetts, and fought at Bunker Hill, Long Island, White Plains, and Princeton. By 1778, he had been made a captain and was suffering through the winter at Valley Forge. While he was gone, one of his three children died, and a fourth --- a daughter conceived on a leave --- was born. Joseph's wife, Sarah Perkins Hodgkins (1751?-1803), took his absence fairly stoically. But the four-year separation grew increasingly difficult. In the couple's letters to each other --- more than a hundred survive --- Joseph revealed the hardships and frustrations of life as a revolutionary soldier, and Sarah the hardships and frustrations of life as a revolutionary ife. Her fears for him notwithstanding, Joseph would not only survive the war but would live to see the fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill.

The "Defelties" (i.e., difficulties) that Joseph referred to were pregnancy and the birth of the daughter whom he would not see for months and whom he called "your child."

JOSEPH TO SARAH

Valleyforge Camp Jany ye 5 1778

My Dear these fue Lines Bring my most affectionate Regards to you hoping they will find you & all friends in as good health as they Leave me at this time through the Goodness of god I Received yours of the 15 of Decemr on Newyears Day and that of ye 7 Last Night and I am Rejoyced to hear that you have Been cumfortabley Carred through all the Defelties that you have Ben Called too in my absents oh that we ware sencible of the goodness of god to us ward and ware more Devoted to his service I wish I could have the satisfaction of seeing you & our Children Esphaly my Little Darughters I am sorry to hear that the Babe is got that Distresing Coff But I hope god will appear for it & Rebuk its Disorder & Restore it to health again and give us an oppertunity of Rejoycing in his goodness

My Dear you say that you have not heard from me since the 17 of Octr I Received your Letter of ye 17 Octor By the Post that minnet I left Albany & Could not Light of him afterwards to send By him But I wrote about ye 16 Novemr from Kings farry & sent it By Capt Blasdon But it seams you have not had that But I have sent By Colol Colman a letter & some Cash wich I gudge you have Received By this time & have sent another By a Post since you say in your Letter of the 7 that you Depend on my Coming home if I am alive & well But My Dear I thought when I wrote Last that I should not Try to get home this winter & wrote you some Reasons why I should not But since I have Received your Letters & seeing you have made some Dependance upon my Coming home therefore out of Reguard to you I intend to Try to get a furlough in about a Month But I am not sarting I shall Be sucksesfull in my attemptes therefore I would not have you Depend too much on it for if you should & I should fail of Coming the Disapointment ould Be the Grater But I will Tell you the Gratest incoredgement that I have of getting home that is I intend to Pertishion to the Genel for Liberty to go to New England to Tak the small Pox & if this Plan fails me I shall have But Little or no hope I Believe I have as grate a Desire to Come home as you can Posibly have of having me for this winters Camppain Beats all for fatague & hardships that Ever I went through But I have Ben Carred through it thus far & Desire to Be thankfull for it we have got our hutts allmost Don for the men But its Reported that Genl How intends to Come & See our new houses & give us a House warming But if he should I hope we shall have all things Ready to Receive him & treet him in Every Respect according to his Desarts you say you have Named your Child Martha & you Did not know weather I should Like the name But I have nothing to say if it suts you I am content I wish I could have the sattisfaction of seeing it So I must conclude at this time By subscribing myself your most affectionate Companion Till Death

Joseph Hodgkins

SARAH TO JOSEPH

Ipswich Februay ye 23 1778

My Dear after my tender regards to you I would inform you that I and my Children are in good health I hope these lines will find you posest of the Same Blessing I now set down to write between hope and fear hopeing you will come home before I get to the Bottom but fearing least you Should not come this winter I heard of an oppertunity Send a letter & I thoght I would not mis of it though you have of writing to me Cousin Perkins told me he Saw you & you was well but he Says he don't think you will come home so he is but one of Jobs comforters I was very glad to hear you was ell but my Dear I must tell you a verbal Letter is what I Should hardly have expected from So near a friend at So greate a distance it seems you are tired of writing I am Sorry you count it troble to write to me Since that is all the way we can have of conversing together I hope you will not be tired of receiveing letters it is true you wrote a few days before but when you was nearer you wrote every day Sometimes I was never tired of reading your Letters I Long to See you am looking for you every day if you Should fail of comeing my troble will be grate surely it will be a troble indeed but I must hasten I have a Sorryful piece of news to tell you it is the Death of Cousin Ephraim Perkins he died on his pasage from the west endies the fifth of January he is much Lamented by all who know him

JOSEPH TO SARAH

Pennsylvania Head Quarters April 17 1778