Excerpt

Excerpt

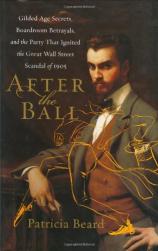

After the Ball: Gilded Age Secrets, Boardroom Betrayals, and the Party That Ignited the Great Wall Street Scandal of 1905

Chapter One

A Death: Henry, 1899

At 120 Broadway, on the third of May, 1899, the workmen were out at dawn. It was their task to drape the Equitable Life Assurance Society in mourning, from the Quincy granite stoop to the mansard roof, all 110 feet of a building that was the protoype of the skyscraper. The fabric was crape -- not the French dress material called crêpe, but a dull gauze scrim that made the world seem dusky to those looking out the windows, and hid the face of the company like a widow behind a veil. In 1899, people knew how to use the color black.

Henry Baldwin Hyde, the handsome, hypnotic entrepreneur whom contemporaries described as being "tall as a pine," with "the eyes of an eagle," was dead. The flags of the United States of America and of the Equitable Life Assurance Society flew at half-mast, as did the flags atop the Mutual and New York Life Insurance companies. Their competition was so fierce that the three were called "the racers," yet New York Life's president had instructed that the headquarters he had just completed, a building eleven stories high and a block long, also be swathed in crape.

Henry Hyde had three obsessions: his company, his son, and his buildings. The home office at 120 Broadway stood on one full acre of land in the heart of Manhattan's business district, and other grand edifices housed his employees in Paris, Madrid, Vienna, Berlin, Melbourne, and Yokohama. Everyone in downtown Manhattan looked at the seven-story-Beaux-Arts-cum-Greek-temple monolith each day, not only because it was magnificent, but to check the weather report communicated by flags from a weather station on the roof. The view was so wide that it was possible to see the sunset across the river in New Jersey, or storm clouds massing north in Harlem. Other signals were commonly recognized, too. When the president of the Equitable sailed to Europe, the company's flags were dipped and raised three times, and the ship replied by blasting its whistle and lowering and raising its colors. This time the flags would stay at half-mast for a week.

Henry Hyde referred to his appetite for architectural grandeur as "building for glory." His offices were an interesting contrast to his own consciously modest stance. He boasted, "I can start from my house uptown in the morning, go to the elevated station and take the train to Rector Street, pass through the Arcade to Broadway and up that street to my office and not be recognized by a single person." He refused interviews, declined to be included in Who's Who in America, never gave permission for his photograph to be published, and believed that seeking or even permitting personal publicity was a lapse in the appearance of rectitude necessary for a man in such a serious business. But he was not reticent about the first important building to represent his company. He fought the appalled directors in 1867 at the end of the Civil War, when the Equitable was worth a little more than $5 million, and spent 80 percent of it to erect his splendid landmark, which took three years to complete.

Until Henry came along, no one had dared to use passenger elevators in an office building. He began with two: They were powered by steam, paneled in tulipwood, decorated with gilt and mirrors, and cost $29,657. The elevators enabled him to build two stories higher than the previous five-story maximum, so he could rent out offices on the top floors. The Equitable Building was such a sensation that, in 1885, the Real Estate Record and Guide recalled, "People came from far and wide to ascend its roof and look down from the dizzy height upon the marvelous stretch of scenery taking in the Bay, the Narrows, Staten Island, the North and East Rivers, and the major portion of New York and Brooklyn." Even the elevator guard towered above other men: John Seaton, the descendant of two of George Washington's slaves, was over six and a half feet tall, although his height was generally described as seven feet. Henry had noticed Seaton in 1874 when he was part of the honor guard that escorted the abolitionist senator Charles Sumner's body to New York, tracked Seaton down, and hired him for his impressive dimensions.

The porticoed and pedimented entrance to the home office had originally been decorated by a John Quincy Adams Ward statue group representing the Goddess of Protection, the Equitable's icon. Over time, the stone began to crumble, and the sculpture had to be removed, which Henry saw as a disappointment, but not an augur. Inside, a two-story-high, two-hundred-foot-long, domed central hall was dominated by a floor-to-ceiling stained-glass window with a center medallion of "the Protection Group," a sweet-faced, classically robed woman standing with a spear in one hand and a shield held like an umbrella in the other, sheltering a young mother and child. The implication was that their husband and father had left them sorrowful but insured. The window was made in France in 1879; a year later, Henry Hyde's beloved first son, little Henry, died at age eight of complications of scarlet fever. When the stained glass was installed, a medallion surrounding a head-and-shoulders portrait of the boy with freshly combed hair and an Eton-style collar and tie was placed at the bottom center of the window. Little Henry was a handsome, dark-haired child; even rendered in glass he looked bright, merry, and good. If he had lived, he would have been brought up to run the Equitable. Instead, his father transferred his love and, ultimately, his stock to James, his younger son.

With both Henry Hydes dead, James would become the majority shareholder. But until he turned thirty the Equitable would be headed by his trustee, James Alexander ...

Excerpted from After the Ball © Copyright 2012 by Patricia Beard. Reprinted with permission by HarperCollins. All rights reserved.

After the Ball: Gilded Age Secrets, Boardroom Betrayals, and the Party That Ignited the Great Wall Street Scandal of 1905

- hardcover: 416 pages

- Publisher: HarperCollins

- ISBN-10: 0060199393

- ISBN-13: 9780060199395