Excerpt

Excerpt

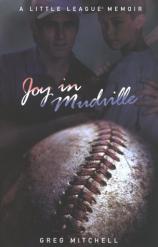

Joy in Mudville: A Little League Memoir

From Chapter One

It's opening night at Memorial Park in Nyack, New York, hard by the Hudson River, and already the Little League season is looking bleak. My Red Sox are trailing, my ace pitcher is getting bombed, and my son has already booted one ball and struck out in his only at bat. Even worse, our uniforms haven't arrived yet, so we are not Red Sox, but Braves, wearing faded, mismatched shirts from a distant decade. We do not look good out there, in any sense. In fact, we don't even look like we belong on this level. We seem young and small and inept, and appearances, in this case, do not lie. Our outfielders can't field. Our catcher can't catch and cannot peg the ball to second base, or even get it back to the pitcher half the time. Our only offensive weapon is the base on balls. Our only hit was a hit batter. We are, in short, the Better Dead Than Red Sox.

And the parents, all potential Steinbrenners, are already getting restless.

It didn't get much better the rest of the year for the team or its manager. We ended up winning two games and losing twelve, and got knocked out of the playoffs in the opening round. My son, Andy, age nine, barely lifted the bat off his shoulder the entire year and finished with a .155 batting average, which is bad, even for a pitcher. Comically, the only one who got injured was me -- completing the 1997 season with a serious arm ailment from stabbing for wild throws.

A year later, however, it was baseball like it ought to be. Renamed the Athletics, we were surely the only Little League team in the nation with an extraterrestrial for a mascot -- hence our nickname, the Aliens. We staged one impossible comeback after another; our battle cry was "Alien Resurrection!" This time Andy would play a pivotal role in the team's thrilling drive to the playoffs, and his manager/father, at a key moment, would deliver a stroke of genius that came to be called the Walk on the Wild Side.

This, then, is a tale of two seasons, the ridiculous and the sublime. It stars my "cardiac kids" -- Matt the Bat, RBI Keiser, Little Stevie Wonder, Cool Taddy Bell, and all the rest. It explores the intersection of two baseball lives, manager and son, and how this produces both profound conflict and ineffable joy. More than that, it is a saga of all fathers and all sons, and baseball in our time, as America's Game enters its third century.

Andy is tall for his age, lanky, brown-eyed, brown-haired, good-looking. He adores his mom. Born in Manhattan, he now prefers Nyack. He's a typical pre-teen American kid, into Game Boy and X-Files, Old Navy and MTV, The Simpsons and Austin Powers, and hiking around our local megalo-mall. We don't let him watch South Park, but he knows every character, gag, and plot line through schoolyard osmosis. Yet his favorite book is To Kill a Mockingbird, his favorite film Saving Private Ryan. He's a talented cartoonist, and a movie maven. He plays electric guitar in a rock band called We Don't Suck.

I tell him, "Andy, if you say you don't suck, all the kids will shout out, 'Yes, you do!' Even if you don't."

"So we'll change our name to We Suck, then they'll yell, 'No, you don't!'"

"Don't bet on it." Little League and rock 'n' roll -- this is how Bruce Springsteen started?

He's our only child, the male baseball heir of his father. That's a lot of pressure, real or imagined. Not long ago the New York Mets' top minor league prospect, Ryan Jaroncyk, quit baseball entirely because he was sick and tired of getting advice from his father -- ever since Little League -- and had come to hate the game. He claimed, in fact, that he had never liked playing ball and had only kept at it to please his dad, a former University of Southern California defensive back. His mother, who had complained about this for years, packed up and left, too, so Dad lost wife and son within the same week.

Obviously there's a lesson there. I think of that story almost every day during the baseball season, and my wife, Barbara Bedway, also a writer, often points out similar ones. Barbara supports Andy playing Little League but sometimes feels his father should not be so involved. She once cited the case of the Little League coach in Illinois who got beat up by another coach after a game, sustaining several broken bones, a lacerated kidney, and a scratched retina. "Hey," I reminded her, "didn't he get $750,000 in a settlement?"

Fortunately our little family remains intact and Andy is still playing ball, happily (for the most part). Sometimes, however, Little League drives us apart -- when it isn't bringing us together.

The American Psychiatric Association recently sponsored a symposium entitled "Youth Sports: Character Building or Child Abuse?" During the rollicking 1998 season I would be accused of both -- in the same game. Youth baseball takes place in a cultural milieu where fistfights between adults can break out on a ball field filled with children. It's the kind of world where an umpire kicks a twelve-year-old catcher out of a playoff game for not wearing a "cup." The catcher was a girl. Coaches, parents, and league officials argued about it for a week. Then the lawyers got involved. Only in America.

Our disastrous 1997 season actually ended on something of a high note. In his first year of pitching, Andy had progressed nicely after recovering from a mid-season wrist sprain, an injury he'd earned sliding off a porch chasing a girl in a game of tag. My wife felt that, as injuries go, this one was almost worth it; until then, he had displayed an almost pathological aversion to the opposite sex. I pointed out that Andy had years to get involved with girls but would never have another rookie season in Little League.

Luckily, his interest in girls faded before his fastball, and he pitched well in the two games we did manage to win that year. At age nine he was holding his own against kids two or three years older. After he hurled his first win in Little League we retrieved the dirt-smudged ball, signed and dated it, stuck it in a plastic globe, and put it on a shelf, joking that one day we'd donate it to Cooperstown (or sell it at auction).

By the end of the year, as we headed into the playoffs, Andy was clearly our best pitcher. How did a 2 and 10 team qualify for the playoffs? Everyone makes the playoffs in our league. But Andy was no prodigy. He was still a below-average hitter and it was uncertain how far he would advance as a pitcher, since he's not especially fond of practicing. For better or worse, he's not one of those kids who live to play ball. When he grows up he wants to be Fox Mulder, not Nellie Fox.

Most games at this level are played down by the Hudson at Nyack's Memorial Park. Nyack is a community of about twelve thousand, counting Upper Nyack and South Nyack -- the three adjacent villages known collectively as "the Nyacks." We're located twenty miles up the river from Manhattan on the west bank of the river across from Tarrytown, the historic Westchester town. From Memorial Park, you can gaze across three miles of spectacular river and admire Washington Irving's Sunnyside estate. He set his most famous story, "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow," nearby.

Nyack dates back three centuries to Indian camps and then Dutch settlements. Today it's a funky river town with a Main Street lined by fine restaurants, antique shops, and a new Starbucks. Some people refer to racially diverse Nyack as the Upper Upper West Side of Manhattan or, getting carried away, "Greenwich Village-on-Hudson." The boyhood home of artist Edward Hopper, it is still favored by slightly offbeat freelance types with moderate incomes -- writers, jazz musicians, and movie and theater people who trek to New York City at odd hours or not at all. It stages one of the wackiest Halloween parades this side of, yes, Greenwich Village.

Decades ago, the town was perhaps best known from the song lyric about taking "a kayak to Nyack." It hit the headlines in 1981 when radical fugitives, including ex-Weatherman Kathy Boudin, robbed a Brinks truck at the nearby Nanuet Mall, then killed a guard and two Nyack cops. One of the getaway cars sped east down Sixth Avenue in Nyack and crashed into a high brick wall surrounding a fine Victorian home on the Hudson.

The house belonged to actress Helen Hayes. Now Rosie O'Donnell lives there.

Among others who call Nyack home are controversial performance artist Karen Finley; movie directors Nancy Savoca and Jonathan Demme; actors Ellen Burstyn, Dennis Boutsikaris, and Deborah Hedwall; AIDs activist Mary Fisher; authors James McBride, Lynn Lauber, and E. Jean Carroll -- and Hall of Fame baseball announcer Bob Wolff. Susanna Styron, daughter of William Styron and director of the film Shadrach, recently arrived in town. It's the kind of place where a kid can go from headlining the middle school play to starring in an NBC television series six months later.

As it happens, one of my neighbors starred as Grizabella in the Broadway production of Cats. My neighbor on the other side is a graphic artist and first cousin of a famous pop singer. She bought the house from a fellow who made Broadway props. When he was working on Titanic he asked Andy (a Titanic buff, pre-Leonardo) to lend him some of his books and models. Walking up the hill in back of our house my wife often runs into an elegant, gray-haired woman who was Carson McCullers's psychiatrist in Nyack.

Karen Finley probably speaks for most when she says she moved to Nyack because she felt it was "integrated and progressive and had a sense of history and identity. It's not a bedroom community." The writer Toni Morrison has a house nearby and co-owns a soul food restaurant in Nyack. When a New Orleans eatery opened on Main Street it felt only right that the owner once played in the Neville Brothers band. Most of these people have raised one or more children in this area, and some of them have played baseball down there at Memorial Park.

Our local Little League, however, reaches beyond Nyack. If anything, it is dominated by players and parents from Valley Cottage, a distinctly different hamlet just up the road, populated by many fine people who are more conventionally suburban, and like it that way.

Excerpted from JOY IN MUDVILLE Copyright (c) 2000 by Greg Mitchell. Reprinted with permission from the publisher, Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved.

Joy in Mudville: A Little League Memoir

- Genres: Nonfiction

- hardcover: 272 pages

- Publisher: Atria

- ISBN-10: 0671035312

- ISBN-13: 9780671035310