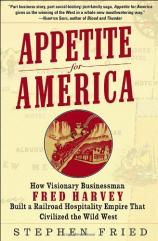

Appetite for America: How Visionary Businessman Fred Harvey Built a Railroad Hospitality Empire That Civilized The Wild West

Review

Appetite for America: How Visionary Businessman Fred Harvey Built a Railroad Hospitality Empire That Civilized The Wild West

Fred Harvey --- both the man and the hospitality industry that bore his name for over 70 years --- invented the chain restaurant business, the chain hotel business, and the chain bookstore business. He became a multi-millionaire, even by monetary standards of the day, by demonstrating how those chains not only could connect a nation but also help hold it together through two world wars, two major stock market crashes and the Great Depression.

If history books had read like APPETITE FOR AMERICA when I was in school, I would have spent a lot more time with my nose in the book instead of staring out the window or watching the clock. Stephen Fried has brought to life in High Definition the Golden Era of American expansion from pre-Civil War to post-World War II. The book is thoroughly researched and vividly narrated in what the author calls the “emerging genre of ‘history buffed,’’’ a style that “dares journalists to bring their investigative and story-telling skills to tales once told only by academics."

The rags-to-riches story of a gentlemanly immigrant who left England in 1853 at age 17 might have been lifted straight from the pages of a Horatio Alger novel, except that it is fact, not fiction. He snared a job in a coffee shop upon his arrival in New York, learning the restaurant business from dishwasher to line cook. He married and moved his wife and young son west to St. Louis to open his own restaurant just as the Civil War broke out. His early prospects were quickly dashed when a deadly civil uprising in St. Louis destroyed his restaurant, and he found himself penniless at age 26. He struck out across what is now Missouri to Leavenworth on the Missouri River just as the railroad business, including the fledgling Santa Fe Railway, was starting to expand.

Harvey sold advertising for a newspaper distributed at train stations and restaurants. The job entailed frequent train travel that he found either a hot or a frigid affair, depending on the season. It was dirty, spine-pounding, cinder-laden and altogether a miserable way to cross the plains. But with nothing more than the wagon ruts of the famous Santa Fe Trail as an alternative and guide, travelers and shippers had no choice. The only food available to travelers west of St. Louis was grabbed from local shacks next to the tracks during the half hour it took to load on coal and water for the next leg of the trip. It consisted of the catch of the day --- fish if near a river or the meat du jour supplied by local cowboys, hunters and Indians, frequently buffalo or deer, prairie chickens or rabbits --- either boiled or fried in fat.

As railroad passenger lists expanded, Harvey’s background in the restaurant business gave him an idea. Why not serve decent, edible meals in clean restaurants, cooked by trained chefs and served on white tablecloths with linen napkins, china and silver by polite and helpful waiters at the fuel stops. He soon discovered that the rough cowboys and hunters who lived beyond the more cosmopolitan cities were uncomfortable being served by black waiters. So he recruited girls from wholesome families and schools who were thoroughly trained in interpersonal skills, manners and food service, immaculately attired in starched white blouses and skirts, and housed in dormitories under strict rules of stern house mothers. “The Harvey Girls” became a branding of the Fred Harvey enterprise and were among the first young women to be gainfully employed in respectable careers.

There began the saga that would provide a fortune for him, his sons and grandsons, and introduce a whole new series of enterprises to the American economy. A movie by that name, starring Judy Garland, spawned the hit song “On the Atchison, Topeka and the Santa Fe” right after World War II.

Harvey’s most famous hotels, the El Tovar and Bright Angel Lodge at Grand Canyon and the La Fonda Inn in Santa Fe, are still in operation. Tourists who wish to stay at the Grand Canyon El Tovar these days must make reservations more than a year in advance. Vast collections of American Indian pottery, jewelry, rugs and furniture once adorned the walls and rooms of many of the lavish hotels designed throughout the west by his protégé, Mary Colter. These treasures are housed in museums from Chicago to Los Angeles, the largest in the Heard Museum in Phoenix. Colter invented the “Santa Fe Style,” which has influenced Southwestern living for decades.

The epilogue, appendices, 17 pages of recipes and menus from the famous restaurants, plus a diary of a current trip along the Santa Fe Trail by Fried and his wife, kept me going straight to the end. For historians, a complete bibliography and author’s notes at the end is provided without the interruptions of footnotes and references in the text. Fried also includes a handy comparison of prices then and now, which I found particularly interesting.

Once in a while, you pick up a book that prompts you to make a list of people you simply must recommend it to. APPETITE FOR AMERICA is one of those books, and the invitation is wholeheartedly extended to our readers at Bookreporter.com.

Reviewed by Roz Shea on December 22, 2010

Appetite for America: How Visionary Businessman Fred Harvey Built a Railroad Hospitality Empire That Civilized The Wild West

- Publication Date: March 23, 2010

- Genres: History, Nonfiction

- Hardcover: 544 pages

- Publisher: Bantam

- ISBN-10: 0553804375

- ISBN-13: 9780553804379